They drag cars full of scrap through the city of Barcelona from the early hours of the morning until the last light of the day. They carry metal, cables, fans, appliances and, in some cases, even bathtubs. “It depends” is the word they repeat the most: they don’t know exactly how much they will sell the materials they collect during the day for. That will be your only income. They speculate that a full cart could sell for around 10 or 20 euros, which on a good day can make a little more than that. Other days, just four or five euros.

The money they make will depend on the stock market price of each material, always leaving room for the intermediaries who transport, store and transform the scrap to make profits. The majority of informal scrap dealers, who are the first link in the chain, do not even have NIE, work permit, residence or access to Social Security. However, they fulfill a fundamental recycling task. They play the hardest part in the process but barely scrape a few cents per kilo of scrap metal. On the other side, the waste collection contracts that benefit from this labor have a value of millions.

According to the Wastecare researchfrom the University of Barcelona, each scrap metal dealer collects about 118 kilos a day in the Catalan capital. Taking into account that there are about 3,200 people dedicated to this work in the city, they move about 380 tons of metal daily. It is equivalent to more than 100,000 tons per year that are recycled thanks to unrecognized work. 75% of informal recyclers come from African countries, among which Senegal stands out, although there are also those from other continents. Their work, which for them is a “survival strategy” in a precarious and vulnerable situation, contributes to improving the circular economy.

Many recyclers arrived via the Canary Islands route, the deadliest

Mohamed is one of them. Despite the rain, he searches through some containers with the car in front, where he accumulates several bags, iron bars, a rickety microwave and an old television. He has lived in Barcelona for three years, of which he spent a month sleeping on the street. He currently shares a flat with other compatriots and spends his days looking for scrap metal to pay the rent and other common expenses. The rest he sends to Senegal, where his mother and sister still live. Mohamed used to be a fisherman, but he found it increasingly difficult to make a living because boats from other countries take most of the fish. Therefore, seeking to improve his situation, he decided to leave.

Aliou, 52 years old and with six children in Senegal, also experienced difficult work situations after almost forty years dedicating himself to different jobs. The last one he had was as a merchant. He made the decision to migrate just a few months ago, after seeing how, time and again, all the products from his stall were stolen. Like many other migrants, he finds himself in paper limbo: he cannot work without documentation and he cannot get documentation without work.

Mohamed, Aliou and also Demba, a 23-year-old Mauritanian, are some of the many informal recyclers who arrived in Spanish territory through the Canary Islands route. All of them, at different times, spent around six “very hard” days on a boat heading to the archipelago, this being the deadliest journey in the world.

All three agree on the reasons that led them to leave their countries: bad policies and the desire to help their families. To this, Demba adds a “situation of inequality and difficulty in obtaining employment” in Mauritania. A country where, according to a Amnesty International reportslavery still persists.

Where is scrap metal sold?

Similar stories are replicated around the warehouses where the scrap metal is sold. Some of the stores have signs; others, no. In both cases it is difficult to talk to the owners who, as the recyclers point out, are usually Spanish. The person you can talk to is the person in charge of the warehouse, usually an African who has been in the country for many years and who manages cash payments.

Karim, the manager of one of the warehouses, explains that they work with many different companies, but that the price is not fixed. What the companies pay them, which in turn depends on the stock market value, will determine how much each person will charge for the contents of their car.

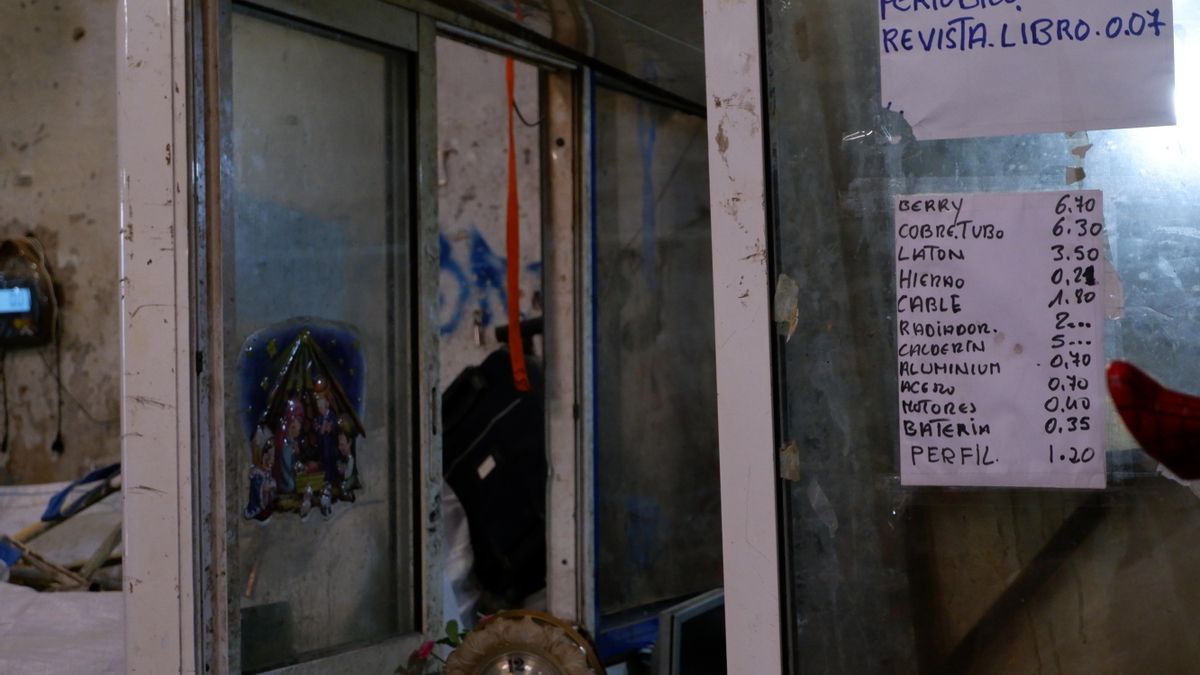

The warehouses are dark, filled with piles of cars, metal and mattresses. Men work there, weighing and placing objects inside the trucks. You can see handwritten signs posted on the wall with a pricing table. They handle large quantities of metal, but not all the materials that are collected pass through spaces like these.

Bouba and Mamadou, two Gambians who are in the area, say that sometimes they sell the scrap metal to individuals who fill their car and go directly to a company to sell by weight. By eliminating a middleman, the profit margin is somewhat higher. However, to sell directly to these companies it is necessary to reach a minimum weight that is only possible to transport when you have a vehicle. In addition, they ask to present an ID. Therefore, for migrants, the intermediary is always necessary.

There are other objects that, although they are not junk, can also provide you with some income. Waiting outside one of the warehouses is Jacob, a man born in Morocco who has been in Spain since the 90s, when his father was able to resort to family reunification. He comes from time to time with an Algerian colleague to buy lamps, dolls, soccer cards and antiques in general. “Sometimes they bring something interesting and we can sell it on the market,” says Jacob.

“It is a way out for people who have no other resources”

Although the majority of informal scrap dealers are migrants, there are also Spaniards. These are people without resources, like Manuel, who has lived on the street since he lost his car. He has been working in scrap metal for almost 20 years, when he was fired from a logistics company during the economic crisis and did not find another job.

He says that before it was very easy to fill several cars in a day because few people dedicated themselves to it, but there are more and more people in vulnerable situations who turn to scrap metal as a means of subsistence. However, he points out that, unlike other parts of Spain, there is no monopoly on the part of certain groups, so anyone can collect and sell scrap metal in Barcelona.

He explains that there is even a certain solidarity: “If you are the first to arrive at a construction site and ask for scrap metal, they may give it to you.” He says that, in addition, there are neighbors who save materials to give them directly to people they know in the neighborhood.

This is confirmed by the Wastecare study, according to which 66% of the citizens surveyed claim to leave objects next to containers with the intention that they be collected by scrap dealers. “It is an outlet for people who have no other resources, like me,” Manuel reflects.

After almost two decades in this sector, Manuel has noticed that wars are a factor that greatly influences the purchase and sale of metals, and that after crises their demand usually increases. “I have seen it many times,” he summarizes. An example of this is the great inflation that the price of aluminum, copper or steel experienced when the war began in Ukraine, as well as various raw materials.

Essential and vulnerable

According to the Recovery Gremi, 30% of the metals recovered in Catalonia are precisely collected by informal scrap dealers who do not have job guarantees or stable economic income. However, the city remunerates the companies hired for that work, benefiting from a vulnerable workforce whose only option is to take or leave the price they are offered.

The Wastecare research reflects how the majority of citizens have a positive perception of people who collect scrap metal, largely because they contribute to sustainability. Thus, 68% believe that they should be hired by the city council. According to the researchers themselves, formalizing their situation or providing facilities for transporting scrap metal would help not only the workers themselves, but also create greater recycling capacity.

#Subsisting #scrap #car #Barcelona #fate #migrants #arrive #Canary #Islands