At the entrance to Rositz, a small communist party’s election poster warns: “Those who vote for AfD vote fascism!” The propaganda from last Sunday’s regional elections still adorns the streets of this town that boasts of its industrial past. Today, no one would say so, but Rositz was the largest rural municipality in Thuringia at the beginning of the last century. It once had festival halls and a theatre for 500 people where thousands of factory workers were entertained. Today, its inhabitants are less than 3,000 and, as a result, there is not even a doctor in the town.

More than half (51.1%) of Rositz residents voted for the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) on Sunday – the highest percentage in the entire district of Altenburg, which is also the Thuringian district where the extremists had the greatest success with 41.3% of the votes. “Well, considering that only half of the population voted, let’s say a quarter voted for the AfD. On the bright side,” says the mayor of Rositz, Steffen Stange, an independent who has been in charge of the municipality since 2006, with a smile.

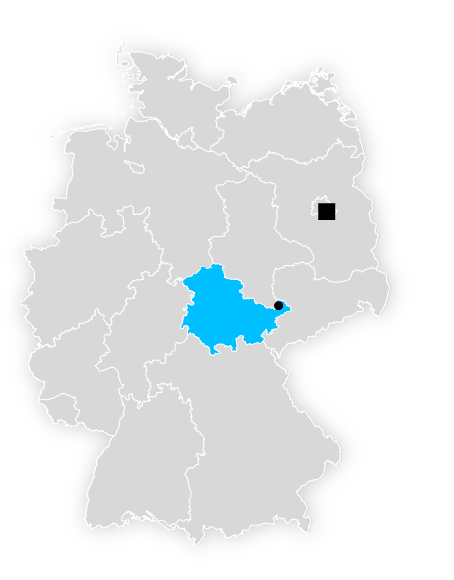

This area of Thuringia embodies one of the problems of rural areas in eastern Germany like few others: depopulation. You can see it as soon as you leave the station in Altenburg, the district capital. The almost ruined building of the former Europäischer Hof restaurant and hotel gives an image of abandonment that is confirmed by the dozens of closed shops on the streets. In 1995, the district of Altenburg had more than 120,000 inhabitants; today it has less than 89,000.

“People want attention, they are protesting,” says Stange, an affable 55-year-old man who speaks to EL PAÍS in his office at the Town Hall, a building built during the time of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) that seems to have been frozen in 1989. “We are a large municipality of 2,800 inhabitants and we no longer have a doctor. People have to go elsewhere for treatment. We still have two schools, but there are no teachers. The hole in our budget is huge; many services are provided by volunteers. People are unhappy and they express it that way,” he insists.

“Do you want to know who I voted for? No problem, the CDU,” says a woman in her sixties who agrees to speak about the election on condition of anonymity. “But I understand why so many people voted for the AfD. It is a reaction against the government, as a challenge to the politicians in Berlin,” she says: “We feel abandoned. They seem to forget that there is life beyond the cities.” That is why she is not worried that the Thuringian extremist party is officially classified as right-wing extremist by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, the German secret service. “I am not saying that there are no Nazis in there; there may be, but not all of them share these extreme ideas,” she says.

Knowing what’s happening outside means understanding what’s going to happen inside, so don’t miss anything.

KEEP READING

There are fewer migrants and asylum seekers in eastern Germany than in the west, but xenophobic and racist attitudes are more prevalent, as recent studies have shown. AfD has based its campaign on anti-immigration messages, also in Rositz, where several posters of the party still hang, depicting a plane and the legend “Summer, sun, remigration”. Remigration was voted the most negative word of the year in Germany. The euphemistic intention does not hide what it means for the ultras: the forced repatriation of millions of people of foreign origin, even those with naturalization.

Mayor Stange says that migration is not a problem in the village. “There are hardly any immigrants!” he exclaims. “We have 40 or 50 people living here from Ukraine who fled the war. And maybe 15 or 20 asylum seekers, Africans. That’s all. Maybe people are afraid of what happens in other places, I don’t know.”

“Rositz is like an enclave in this area, that’s true,” admits Daniel Bär, the only respondent who agreed to give his name. He finishes serving a customer in his shop specialising in lawnmowers and asks: “Have you been to Altenburg, in Gera? There is immigration there and of course it is a problem. There are other reasons for voting for AfD, but the main ones are dissatisfaction and immigration. Muslim immigration, more specifically,” he says. “We don’t want to become North Rhine-Westphalia,” he says, referring to the land from the west, the most populated in the country, which has welcomed the largest number of refugees in recent years.

He prefers not to say what he voted for. “We don’t talk about that here,” he says, pointing to his colleague, who smiles and nods. People, says Bär, know that AfD is not the solution to the problems, but they vote for them anyway because they are not a party “of the establishment”.

The far-right party won in Thuringia with 32.8% of the vote and managed to become the second force in Saxony, with 30.6%, just over one point behind the Christian Democrats of the CDU, who are now facing complicated multi-party negotiations to try to form coalition governments without the presence of the far-right party. AfD describes the cordon sanitaire applied by the other parties as “unconstitutional” and claims its right to govern as the party with the most votes.

Another man, who asked to be given only his surname, Junge, says that he voted for the CDU for “strategic reasons”, i.e. to support the strongest against the AfD. He is actually a left-wing voter, he says. “Reunification was not balanced. Here in the east there was a lot of euphoria at the beginning, but then we realised that we had been abandoned. It is not just a question of wealth or jobs, but also of identity,” says the retired engineer: “People feel forgotten and misunderstood, but the migration factor is relevant. I think only 5% of AfD voters are racist; the rest are not, but they are outraged when they see Afghan refugees going on holiday to their country.”

Follow all the international information at Facebook and Xor in our weekly newsletter.

#People #unhappy #protest #eastern #German #town #ultras #swept