“If the reader doesn’t know enough, he can really feel wrong”. Ville-Juhani Sutinen, who won Tieto-Finlandia on Wednesday, writes about the worship of iconic works.

Pretty accurate twenty years ago, as a young poet and student of literature, I entered an antique store with the intention of making discoveries. However, after half an hour of pegging, I hadn’t seen any discharge.

Since I was determined to find something, I hurriedly grabbed the first Great Novel I came across. It happened to be by Mikhail Bulgakov Satan arrives in Moscow. When I took the book to the cash register, the divar salesman stated dryly: “Let’s go with the classic line.”

It is good that there are books classified as classics. The canon, which is instilled in us by school, friends and a bunch of established historians, works like an algorithm that filters out what is outdated, trivial or otherwise just too insignificant to survive in a changing world. The classics are supposed to have something universal that lives across time and place.

Author and translator Ville-Juhani Sutinen was awarded at the non-fiction Finlandia in Helsinki on November 30.

Right here however, there is also a problem with classic books. At some point, they start to be read as too universal, in which case their connection to their own time fades, and the works turn into Great Novels.

Some classics are overrated. Or maybe overrated is a bad word, because these books do deserve appreciation, but not for the reasons one imagines. We should probably talk about misappreciated classics.

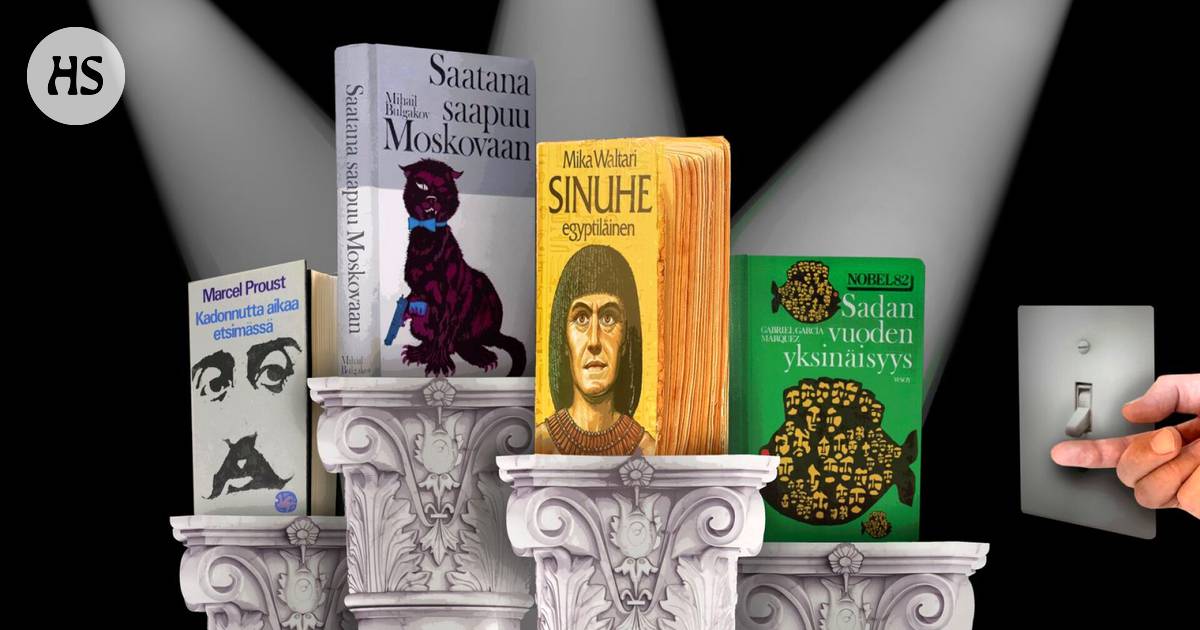

Such works include, among others by Marcel Proust Looking for lost time, Gabriel García Márquez One Hundred Years of Solitude and Mika Waltarin Sinuhe Egyptian. This shortlist includes many favorite works, so I emphasize that I do not consider these novels to be bad. I’m just saying that they are considered good for the wrong reason.

Proust tries too hard to be a great writer and achieves something with it, but if all amateurs who try too hard were defined as classics, there would be a backlog in the canon. One Hundred Years of Solitude again bursts with symbolism, which makes it mysterious, but the book also gets tired under the extravagant allegory. Yours on the other hand, it’s a perfect reading novel, because it’s written so loosely that it doesn’t burden even a browser of click headlines.

Maybe the biggest among the misappreciated classics is Bulgakov’s Satan arrives in Moscow. Many features associated with classic books, such as the concept of the universality of the novel and the idea of larger-than-life art, are concentrated in it. In addition, besserwissers can use knoppie knowledge when remembering, without exception, to state that the name of the original work is different from the one by which Finns know the book.

Satan arrives in Moscow represents to the modern reader the mythical Russian soul, the writer’s fight against tyranny, and the Great Roman polished into a diamond under the yoke of oppression. More abstractly, it reflects creativity in the midst of chaos, art for art’s sake as the world plunges into destruction.

For these reasons, I also picked it up in an antique store: it was a safe bet for a dilettante like me that couldn’t go wrong.

I’m afraid, that Bulgakov himself would have considered such interpretations devilish. He had the right reasons for writing his work. However, these historical, social and personal motives do not survive the survival of the classic.

At the same time, Bulgakov’s real relationship with power is forgotten: the how Stalin also protected him, and how Bulgakov used this popularity to his advantage to get his books published and his plays into theaters, as any writer would surely have done.

A similar oblivion plagues all misappreciated classics. Looking for lost time today represents over-decorated postcard nostalgia, nothing else. One hundred years of solitude is known to be an allegory of Colombia, but the details of the country’s social framework are obscured in the face of the assumed universality.

And To you the universal human message is emphasized because it would be too difficult to find out what people were really like and how they acted in ancient Egypt – which is no wonder, since Waltari himself did not bother to think about how the historical context affects emotions, thinking and even senses.

I myself read these books and many other misappreciated classics for the first time as a young literary enthusiast. I didn’t know much about the background context of the novels: a war was a war, be it the first or the second, and a dictator a dictator, be it Lenin or Stalin. But this is not the case. It all matters.

Contemporary culture emphasizes feeling instead of reason, intuition instead of knowledge. When reading a novel, it is considered important to identify with the characters and experience the world of the work as true. However, it is not enough.

Rational thinking and comprehensive background information are also needed so that the book can be interpreted in a way that respects the work and its author.

Many readings are possible, but not any reading is correct. If we don’t know enough about Russian history, society and culture, it’s impossible for us to understand Raskolnikov no matter how much we hang out with him.

I guess this shouldn’t really be said nowadays, when every opinion is equally important and everyone’s feelings are equally valuable, but if the reader doesn’t know enough, he can really feel wrong.

As we read classics as classics, we forget reality and move to the world of myths. However, literature is not a higher sphere of truth, but is bound up with things like society, politics and technology, and even crude banalities like time and money.

Therefore, these issues cannot be ignored when looking at literary classics. Art is not larger than life. Art is born from life.

When praising Bulgakov’s intransigence, isn’t it also praising the myth of the suffering artist and thus indirectly the tyranny that, by causing pain, distills art to the fore?

I am sure that if Bulgakov had not lived under a repressive system and in constant uncertainty about publication and livelihood, but had lived in present-day Finland and enjoyed a grant from the Kone Foundation, Satan arrives in Moscow would be a well-thought-out and polished piece, and thus truly worthy of a classic.

#Essay #people #misread #classic #novels #claims #Finlandia #winner #VilleJuhani #Sutinen

/s3/static.nrc.nl/images/gn4/stripped/data114761488-3d9710.jpg)