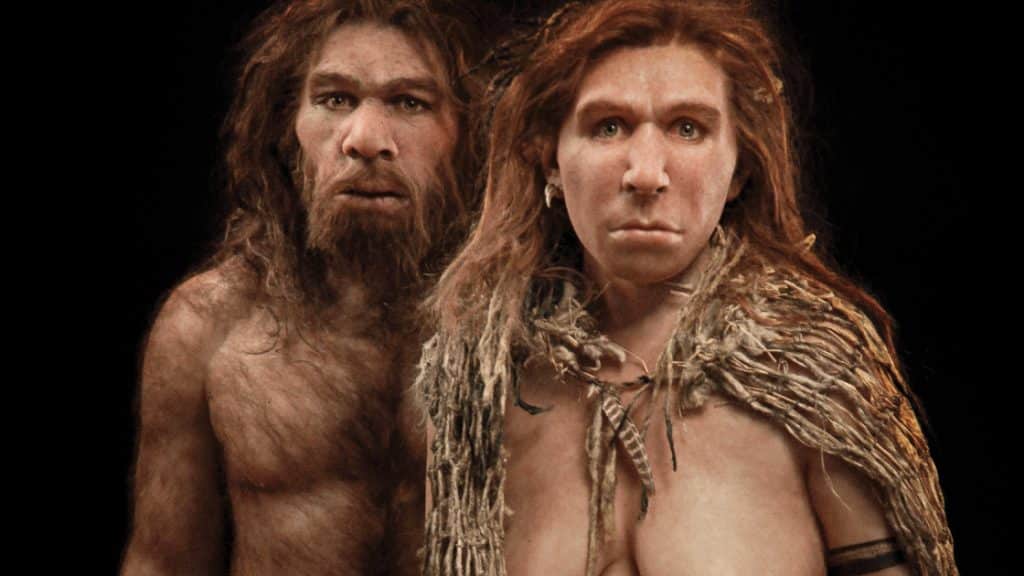

When i first humans they evolved from ape-like ancestors, came down from trees, started walking upright, and lost their fur. But without fur, our ancestors would have been exposed to the elements. They would have needed protective clothing.

The first clothes of humans

So when did humans start wearing clothes? This is a tricky question, because clothes don’t survive the way artifacts made of stone, bone, and other hard materials do. Instead, scientists need to get creative. The evidence used to answer this question comes from a few major sources, including bones bearing evidence of flaying, sewing needles and awls, and lice.

“We tried to understand what changes occurred in the evolutionary history of lice that might be related to the loss of body hair in humans, and then the subsequent acquisition of the use of clothing in humans,” David Reed, told Live, a biologist at the University of Florida.

Lice are incredibly specialized in their habitats; a type that evolved to grasp human head hair wouldn’t survive among human pubic hair, for example. But before our ancestors lost their fur, those lice probably roamed all over their bodies.

Then, by examining DNA to reveal the evolutionary history of lice, scientists estimated that these two types diverged about 3 million years ago. However, a study of human genetics indicates that we lost our hair about 1.2 million years ago. Taken together, these studies suggest a time frame when our ancestors lost their fur.

Another type of lice has evolved to live in human clothing. These lice are generalists that can live on a wide variety of fibers.

“They feed on average once a day – they gorge themselves, which is disgusting – and then retreat into their clothing, where they’re safe,” Reed said.

By looking at when lice separated from clothing, Reed and his team estimated that anatomically modern humans began regularly wearing simple clothing about 170,000 years ago, during the penultimate Ice Age.

There is evidence that hominids – the group that includes modern humans and our closely related extinct relatives – wore clothes long before then. According to research published by Ivo Verheijen, a doctoral candidate at the University of Tübingen in Germany, markings on bear bones found at the Paleolithic site of Schöningen in Germany suggest that hominins, perhaps Homo heidelbergensis, wore bear skins to keep themselves safe. hot about 300,000 years ago. and colleagues in April 2023.

“If you want to remove the skin of an animal, the cut marks you leave most are on the ribs, skull, hands and feet. And that’s exactly what we found in Schöningen,” Verheijen told LiveScience.

“We started comparing it to other sites from around the same time, and they also have cut marks on the hands, feet and skulls. So there seems to be a pattern in this time period of people exploiting bears for their pelts.”

Evidence of flaying is not necessarily evidence of the existence of clothing; hominids could have used these skins to build shelter, for example. But because temperatures were about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) colder on average at the time, people likely used these skins to keep warm, Verheijen said.

“People had to be active to collect food in the landscape,” Verheijen added. “So some kind of clothing must have been necessary to survive here.”

But if there is evidence of clothing dating back 300,000 years, and clothing lice didn’t evolve until 170,000 years ago, what happened in the meantime?

Lice tests “can only measure when humans wore clothes very regularly because lice have to feed on human skin” regularly, Ian Gilligan, an honorary fellow at the University of Sydney’s School of Humanities, told LiveScience. “So if someone wears a piece of clothing one day and then doesn’t use it for another week, the lice won’t survive,” he said.

Furthermore, the lineage of clothes lice we studied may not be the only one in existence. “There are probably other lice that have infested clothing off and on over the last few million years,” Gilligan said.

Furthermore, it is likely that different human groups have started and stopped wearing clothes several times throughout history.

For example, between 32,000 and 12,000 years ago – until the end of the last ice age – Tasmanian Aboriginal people retreated into caves, probably to protect themselves from the cold. But the archaeological record also shows evidence that they made clothing, including skin scraping tools used to scrape animal skins and bone awls used to make holes for sewing.

“Skin scraping tools and bone awls dating back 12,000 years to the mid-Holocene [da 11.700 anni fa ad oggi] – those tools just disappeared from the archaeological record,” Gilligan said. He noted that “they elaborately decorated their bodies, colored their hair, painted themselves, had scarifications, so they didn’t need clothes.”

Why didn’t all primates evolve into humans?

As we migrated around the world, inventing agriculture and visiting the moon, chimpanzees – our closest living relatives – remained in the trees, where they ate fruit and hunted monkeys.

The modern chimpanzeeWe have been around longer than modern humans (less than 1 million years compared to 300,000 for Homo sapiens, according to the most recent estimates), but we have been on separate evolutionary paths for 6 or 7 million years. If we think of chimpanzees as our cousins, our last common ancestor is like a great, great grandmother with only two living descendants.

Why did one of its evolutionary descendants achieve so much more than the other?

“The reason other primates aren’t evolving into humans is that they’re doing well,” said Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. All primates alive today, including mountain gorillas in Uganda, howler monkeys in the Americas, and lemurs in Madagascar, have been shown to thrive in their natural habitats.

“Evolution is not a progression,” said Lynne Isbell, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis. “It’s about how organisms adapt to their current environments.”

In the eyes of scientists who study evolution, humans are not “more evolved” than other primates, and we certainly have not won the so-called evolutionary game.

While extreme adaptability allows humans to manipulate very different environments to suit our needs, that ability is not enough to place humans at the top of the evolutionary ladder.

Take, for example, ants. “The ants are as successful or more successful than us,” Isbell told LiveScience. “There are many more ants in the world than humans, and they are well adapted to where they live.”

Although ants didn’t develop writing (even though they invented agriculture long before we existed), they are hugely successful insects. They just aren’t obviously excellent at all the things humans tend to care about, which are the things they excel at.

“We have this idea that the fittest is the strongest or the fastest, but all you have to do to win the evolutionary game is survive and reproduce,” Pobiner said.

The divergence of our ancestors from ancestral chimpanzees is a good example. While we don’t have a complete fossil record of humans or chimpanzees, scientists have combined fossil evidence with genetic and behavioral clues gleaned from living primates to learn about the now-extinct species whose descendants would become humans and chimpanzees.

“We don’t have his remains, and I’m not sure we would be able to place him with certainty in the human lineage if we did,” Isbell said. Scientists think this creature looked more like a chimpanzee than a human, and likely spent most of its time in the canopy of forests thick enough that it could travel from tree to tree without touching the ground, Isbell said.

Scientists believe that ancestral humans began to distinguish themselves from ancestral chimpanzees when they began spending more time on earth. Perhaps our ancestors searched for food while exploring new habitats, Isbell said.

“Our early ancestors who diverged from our common ancestor with chimpanzees would have been adept at both climbing trees and walking on the ground,” Isbell said.

It was more recently – perhaps 3 million years ago – that these ancestors’ legs began to lengthen and their big toes pointed forward, allowing them to become mostly full-time walkers.

“Probably some differences in habitat selection would have been the first notable behavioral change,” Isbell said. “To make bipedalism work, our ancestors would have gone into habitats that didn’t have closed canopies. They would have had to travel more over the ground in places where the trees were more extensive.”

The rest is the history of human evolution. As for chimpanzees, just because they stayed in the trees doesn’t mean they stopped evolving. A genetic analysis published in 2010 suggests that their ancestors split from ancestral bonobos 930,000 years ago, and that the ancestors of three living subspecies diverged 460,000 years ago. Central and Eastern chimpanzees became distinct only 93,000 years ago.

“They’re clearly doing a good job as chimpanzees,” Pobiner said. “They’re still around, and as long as we don’t destroy their habitat, they probably will be” for many years to come.

#humans #start #wearing #clothes