On the night of March 31, 1964, the Brazilian military deposed the legitimate president, the leftist João Goulart, in a bloodless coup. A dictatorship began that would last more than two decades. In the midst of the Cold War, the elites were furiously anti-communist and Goulart promised agrarian reform and public policies for the working class. Four years later, the generals closed Congress and toughened repression through the Institutional Ato No. 5. Brazil only restored democracy in 1985. For the many supporters of the coup, that was a revolution so that Brazil would not fall into the clutches of communism, a reading of the constitutional breakdown defended by Jair Bolsonaro. During his presidency the 1964 coup was officially celebrated in the barracks. The current president, the leftist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva Lula, has wanted a low-profile 60th anniversary so as not to bother the Armed Forces after the previous president and several of his general ministers have been accused of coup plotting for the most serious attack. to democracy since the end of the dictatorship with the assault on the headquarters of the three powers in Brasilia in January 2023.

This is a review of some moments of the military regime and the transition to democracy.

The Truth Commission

The Truth Commission published the official account in 2014 after listening to victims, witnesses and holding public hearings. The report counted 434 deaths and missing persons, in addition to documenting the systematic practice of arbitrary detentions, torture, executions, forced disappearances… And it also left the names and surnames of 377 repressors for history. The Amnesty law that exempted them from sitting on the bench freed thousands of political prisoners. One of the most infamous torture centers in São Paulo was converted into the Resistance Memorial.

The 1,300 pages of the final report They include shocking passages such as the testimony of Isabel Fávero: “On the third or fourth day of being imprisoned I began to feel like I was having an abortion, I was two months pregnant. I was bleeding a lot, I had no way to clean myself, I used toilet paper, and I already smelled bad, I was dirty, so I think, I'm almost certain, that they didn't rape me, because they constantly threatened me, I disgusted them. (…) Surely it was that, They got angry when they saw me dirty, bleeding and smelling bad, and that made them even more angry, and they hit me even more.”

Killing of indigenous people

The Truth Commission did not include indigenous people in the official number of those murdered by the dictatorship, but it did record that at least 8,350 died. by action or omission of State agents between 1946-1985. They killed them to plunder their lands, to evict them, from contagion of diseases for which they were not immunized, in prison, from torture and mistreatment. The towns of Cinta-Larga and Waimiri-Atroari, with thousands of deaths each, were the most affected.

The most detailed information about the ruthless persecution of indigenous people at that time is an official report prepared in 1967 and which was missing for almost half a century. The one known as Figueiredo Report concluded that “lack of assistance is the most effective way to commit murder. Hunger, plague and mistreatment are decimating brave and strong people.”

After traveling 16,000 kilometers, prosecutor Jader de Figueiredo prepared a chilling document of more than 5,000 pages that took his name. “The Indian Protection Service has degenerated to such an extent that it persecutes them to the point of extermination,” he wrote. The military's policy to clear the Amazon included machine gunning from the air, launching of dynamite, smallpox inoculation, and donations of sugar mixed with strychnine. In 2013, a researcher, Marcelo Zelic, rescued it from oblivion in the Government archives and disclosed its brutal content.

President, victim of torture

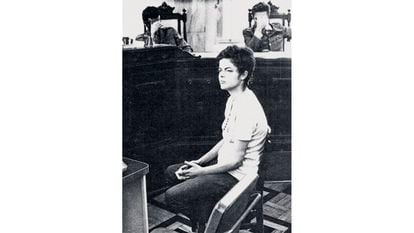

in Rio de Janeiro, in 1970. National Archive of the Truth Commission

Dilma Rousseff, 76, went down in history as the first female president of Brazil, but it usually goes more unnoticed that she was the first torture victim during the dictatorship to reach the head of state. It was she who created the Truth Commission in 2012, a decision for which the military did not forgive her.

A far-left militant, she never shot herself, but that did not save her from going to prison for three years when she entered her twenties (between 1965 and 1968). She suffered torture sessions that marked her forever, physically and psychologically. She was beaten so severely that her jaw was dislodged and several teeth were knocked out. “The torture marks are part of me. I am that,” she testified in 2001 before a commission that managed compensation for those who were retaliated against. “The worst thing about torture was waiting. Waiting to get hit,” she revealed.

At the worst moment of his political career, when Congress was voting on his impeachmentdeputy Jair Bolsonaro starred in an abject moment: the retired and revisionist military man dedicated his vote in favor of impeachment to the president's torturer, Colonel Carlos Alberto Brilhante Ustra.

Lula from A to Z

Tell the biography Lula, by Fernando Morais, that the current president did not take a dim view of the military assuming power in 1964 to restore order. But he was not spared from going to jail either. Already in the transition, when in 1989 he stood for election for the first time, the Air Force intelligence service developed a glossary, according to recently published the newspaper State, which gathered statements from Lula so that the barracks would understand who that unionist was who fought against the dictatorship with a strike. The confidential report concludes that “the charismatic union leader acquired a political personality in the PT [Partido de los Trabajadores] and, leading a brave and noisy party, he took on more daring flights.” Lula lost three presidential elections before winning in 2002.

Against censorship, Camões

In 1972 the censors arrived at the editorial office of State. They reviewed the news and editorial that would go into the next day's print edition. They raised everything that bothered the regime. As usual in dictatorships, what was striking was the newspaper's reaction. He refused to change the design and resorted to ingenuity. Every time a news item or an opinion column was censored and, therefore, left a gap, they would fill it with verses of The Lusiads, by the Portuguese Luís de Camões. An idea proposed by the journalist who directed the film section and the obituaries section, António Carvalho Mendes.

The first verse replaced a news story about the episcopal conference and Pedro Casaldáliga, the bishop of the forgotten and preacher of Liberation Theology. They published verses from the great epic of Camões 655 times.

It is forbidden to prohibit

When Jair Bolsonaro won the election in 2018, Caetano Veloso released a playlist on Spotify that included It is forbidden to prohibit (prohibition is prohibited), composed half a century earlier, in 1968, in the wake of May '68 and in the leaden years of the Brazilian dictatorship. Brazilian popular music and the guitar rock that came from the United States fought a tough duel when Caetano presented it at a concert in São Paulo that ended with loud boos. The composer and singer burst out with a “you're not understanding anything!”, followed by a speech against the conservatism of the public.

At the end of that year, President-General Artur Costa e Silva promulgated the Institutional Ato No. 5, known in Brazil as AI5, which closed Congress and strengthened the dictatorship. Days later, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were arrested, banished to Bahia months later and then sent into exile that took them to London.

Globe and the error of 1964

Or Globethe newspaper of the Globo media group, the most important in Brazil, published in 2013 an editorial titled Editorial support for the '64 coup was a mistake. I remembered the text that “Or Globe agreed with the intervention of the military along

with other major newspapers, such as The State of São Paulo (known as State), Folha de S.Paulo (…) to name a few. An important part of the population did the same, with express support in demonstrations.” The editorialist concludes that “in light of history, there is no reason not to recognize today, explicitly, that the support was a mistake (…). Democracy is an absolute value. (…) Only she can save herself.”

The newspaper claimed that this conclusion was the result of years of internal discussions, but the definitive impulse to publish it, precisely in August 2013, was the massive demonstrations against lifelong politics and a chorus that shouted: “The truth is hard, Globo supported the dictatorship.”

Party to bury censorship

On July 29, 1985, at eight in the afternoon, some 700 artists and intellectuals gathered at the Casa Grande Theater in Rio de Janeiro to solemnly bury the censorship. The new civil Government had been in office for three months. The Minister of Justice had called them to make official the end of the persecution of the culture that displeased the military. The feared censor Solange Hernandes, who silenced 2,500 songs, would have to dedicate herself to something else because the minister declared censorship extinct and announced that from then on a council in defense of freedom of expression would analyze books, records, plays, soap operas… to classify them by age.

Follow all the information from El PAÍS América in Facebook and xor in our weekly newsletter.

#dictatorship #Brazil #scenes #repression #indigenous #people #president #Camões #Globo39s #error