Last night on Married At First Sight Australia, Eden revealed she'd be hiding a terrible secret. Another bride – who I won't reveal because SPOILERS, obviously – had texted her asking if she could borrow a top, so she could wear it to… see her ex-boyfriend.

Shocking! Although honestly, for MAFS it's actually not that shocking at all. A couple of episodes ago, at the weekly dinner party, a man – who always seems to be just moderately sunburnt – told another man to “put a muzzle on your wife.” Another guy decided to call it quits straight after the first week honeymoon because his match, a psychic medium, kept interrupting him mid-conversation to receive messages from the dead.

This stuff is horrible – but what brilliant TV! Pure reality television. In other words: thrilling and horrifying, potentially exploitative, low-brow, but also, maybe, if you squint at it, kind of profound?

This sounds like at least part of what developer Nicole He is trying to capture with The Crush House, a game she calls a “thirst-person shooter” set in a kind of late-90s-slash-present-day Big Brother Malibu Barbie Terrace House, which also features a mystery slide.

He is a former creative technologist at Google, a role she described as “like a programmer, but doing kind of experimental projects – or doing things with experimental new technology basically – often playful projects, making art, even with technology.” She's previously got an AI model to interview Billie Eilish, and created a True Love Tinder Robot, effectively a big ugly hand that mashes the screen of a phone to swipe left or right based on your “feelings”, like a good old fashioned Love Tester machine for the modern day. “It's an industry that's very different from games, mostly because the funding model's very different,” He said, “but there's a lot of overlap on a creative level, and from the technical angle.”

With The Crush House, He seems to be bringing the same, slightly peevish eye to things. Ostensibly the setup here is that you are the sole producer and cameraperson on a reality TV show set in the 90s. Responding to prompts from your PA over the radio, you'll wake up on a camp bed in the Crush House basement, take a look at what “thirsts” your audience members have that day, and attempt to satisfy the increasingly rampant demands with what you shoot on your handheld camera, and how you shoot it.

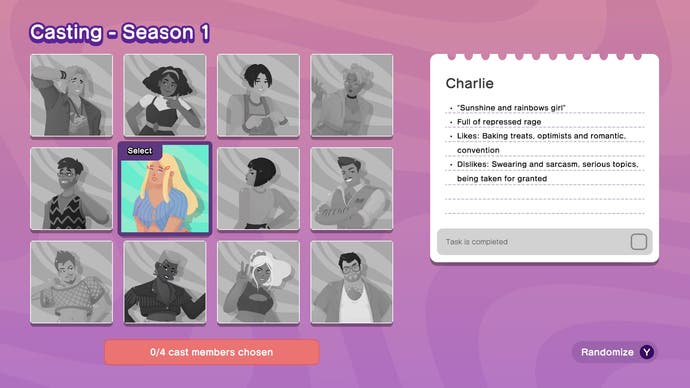

The outcomes are immediately ridiculous. After setting up our house for the demo by picking from three sets of four housemates (in the full game you'll pick each one separately; this was just set up for us to get into things faster), they'll enter one by one and react to each other – as will the audience, via live chat in Twitch-style sidebar on your HUD. The housemates' unique characteristics will dictate their chemistry, or lack thereof, and lead to the usual kinds of reality TV outcomes: smooching, camaraderie, Sims-style flappy-armed fistfights, and so on.

As audience preferences begin to filter through, you'll need to start getting a bit more deliberate with your cinematography. Film buffs enjoy creative angles, for instance. Gardeners like it when you get some plants in the background. Butt guys like it when you can see people's backsides, voyeurs like it when you shoot people from far away and feel like a bit of a creep in doing so. As the game progresses with each day these'll get progressively more challenging however, leading to a requirement for cleverly assembled combos (and mentioned ridiculousness: one popular shot involved a Dutch angle view of a toilet, appeasing the film buffs and schadenfreude fans at once ).

Is that an intentional comment, I wondered, on the nonsensical position any creative can find themselves in when thinking only about giving an audience what they want? “Yeah, absolutely,” He said.

“I think this is true for a lot of games where you're doing a job, right? You're like existing in some kind of capitalist structure, where someone's telling you to do something and you have to do it… and I think it's actually very true, particularly for reality TV audiences, to be quite demanding – because these are actually real people that exist in the world, right? Go on any reality star's Instagram and people are going nuts on the comments asking for this or that, wanting things like insight into their private lives.

“A lot of this game is thematically about that relationship,” He says, “a little bit of the parasocial relationships that we have with these people – or with not just reality stars, any kind of celebrities, just being part of an audience and then being a person who's trying to survive.”

Beyond the slightly absurdist comedy of the day-to-day cycle, however, there's a twist, as The Crush House hints at something that taps into the grimmer side of reality TV production. The first sign you see on leaving your basement bedroom, for instance, reminds you of the two key rules: the audience is always right, and don't talk to the cast. Call it Checkov's sign, as inevitably that rule is broken: one day a cast member will come to you in secret, after the day's filming is over and when you should be in bed, to request a favor.

In this case it was innocent enough – an egotistical character wanted us to film him in a way where only his face was visible while he talked to his love interest, so his own fans didn't get annoyed at seeing him with someone else – but naturally, on the breaking of the rule things begin to unravel. A voice calls you to a previously-closed elevator beneath the house, where the demo ends.

“We are trying to sort of hint towards the dark edge of the things you might uncover – because obviously we're making fiction, so we can ramp it up however you want – but I think when you watch reality TV, it's a lot of like, 'I know this is fake, so what is actually going on in the backdrop?', right? Like what is this person actually here to do? They say they're here to do one thing and actually it's another, or to find love, or whatever – but is that what they actually want? And also, how are they being treated behind the scenes?”

An example Nicole He gives is Love is Blind, a show where people date each other in 'pods' where they can't see the person they're dating, and 'propose' to one another purely off the back of those conversations. In that show, “and I think in a lot of shows actually,” He points out, “they're not allowed to know what time of day it is – which I think is actually torture in some countries…”

It's that “dark edge” that sets The Crush House apart, at least for now. I asked He about the way many people – myself included at times – pass off their enjoyment of reality TV as a kind of ironic enjoyment, or guilty pleasure, rather than just admitting something they genuinely enjoy doing.

“The ironic enjoyment thing is interesting because it sort of gets at this thing where, when you watch reality TV, you experience a lot of the same emotions you experience when you watch horror – the sort of dread and the cringe. Fear even, in the anticipation. Those are some of the emotions we also want the player to experience – both in the kind of day-to-day reality TV stuff, just watching the things happen, but also in the larger story. A lot of people are like 'Oh I like to hate watching reality TV' – what is hate watching? You're having a great time, experiencing human emotion within this media.”

That darker edge of real reality TV has led to some funny situations – there have been times, He said, where the team felt an idea was “maybe too extreme – but then when you realize you can't actually top how insane and extreme things actually are in real reality TV. Like the horrible things that people do to those people? It's almost like we have more sympathy towards the fake characters, the way we treat them, than what actually happens in reality. All that stuff I think is very interesting in the subject – and the kind of stuff that we want to explore in the game around this subject.”

Much of He's work in the past has focused on the internet or technology as a whole, but as she said towards the end of the demo, it's a natural fit to move from that to video games – and in particular with the help from Nerial, the studio she's working with for The Crush House, which previously made indie hits Reigns and Card Shark.

“Obviously The Crush House is, in many ways, completely different from anything I've ever done before, it also, I think, still gets at similar themes of even the smaller projects that I did in the past – about our relationship to the internet, to media, to each other mediated by the internet.

“Even though this is not about the internet or something like that, the tension, the relationship between the audiences, the commenters, the character, the cast members, you as a person creating the content – it's all very relevant.”

#Crush #House #thirstperson #shooter #holds #mirror #reality #production