Writer. Intellectual. Patriot. Coup. There is no qualifier capable of containing Yukio Mishima’s genius, the most famous Japanese writer of the twentieth century. Man of arms and lettershe conjured his destiny with the pen and consumed it with the sword, leaving behind … Yes a legacy as problematic as fascinating. In it centenaryhis figure continues to challenge the separation between art and artist, between creation and life.

Kimitake Hiraoka was born on January 14, 1925 in Tokyo, beginning of such an extraordinary existence that requires being narrated in reverse order. Forty -five years later and under another name, he introduced the edge of a dagger into his entrails; A ‘harakiri’ as an end point having failed in his attempt to cause a military uprising against the constitutional order. In between, an eternal work in struggle with its fleeting biography.

“Yukio Mishima is still one of the best known authors of modern Japan,” says Masao Saito, a professor of Japanese literature at Osaka University. «In fact, his books are read more than those of Yasunari Kawabata or Kenzaburo Oeboth winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature». Up to five times between 1963 and 1968 was Mishima nominated for the award, but his political radicalism frustrated each attempt. That last year the distinction fell to his mentor, Kawabata. “I ignore why I have given me the Nobel to me, there were Mishima,” he confessed. “A literary talent like yours is only produced by humanity every two or three centuries.”

This discredit even the artistic greatness of Mishima in his homeland, although in Saito’s opinion less and less. «His political opinions and the dramatic way in which he died have influenced the perception of their work, sometimes preventing an objective evaluation. With the passage of time, we may be entering a new stage ». The academic stands out, for example, the recent reprint of the novel ‘A life for sale’ – published in Spain by Editorial Alliance, such as the majority -, which has achieved 300,000 copies sold and a film adaptation.

Ceremony in Tokyo in 2010 on the 40th anniversary of his suicide

AFP

“Despite their historical importance in Japanese literature, Mishima’s books can be quite difficult to understand, which today makes them a challenge for younger readers,” says Saito. «Mishima was a writer with an incredibly broad expression range. While it is true that he wrote complex and demanding novelsalso produced entertainment works that captivated the general public. In recent years, the latter have experienced a revaluation and have gained greater appreciation ».

Literary excellence and challenge to the established order They represent two inextricable dimensions in Mishima’s trajectory since the appearance of his second novel, ‘Concessions of a mask’. This recreates the youth of a homosexual boy in Japan of principles and mid -century, self -fiction of synchronous intimacy: its privileged sensitivity amalgam family, western canon and erotic drives with the national identity crisis after the defeat in World War II .

The brill -successing book raised the author to the condition of celebrity Before complying with the 25th Japanese conservatism, the confession of everything inappropriate in him gained approval and praise, a recurring tonic in a life marked by contradictions and extremes.

“The impact of ‘confessions of a mask’ can be explained in two ways,” says Eri Watanabe, a professor of humanities at Osaka University. «First, Japanese society maintains a tradition of homosexuality Since premodern times. Young priests of temples and artists, for example, sometimes associated with political authorities through a male homosexual culture. This has also been present in the army. In that sense, Mishima became the very incarnation of Japanese military culture, “he says. »Secondly, Japanese society is one of the most sexualized and sexist in the world, and I think that ‘confessions of a mask’ was consumed more as pornography that as problematic homosexual literature ».

Exhibition about Mishima at the Gakushuin school in Tokyo

From there, Mishima produced a large and acclaimed corpus composed of 35 novels, 25 plays, 8 volumes of essays and even some feature film. All this constitutes a Beauty Studywhose maximum splendor always finds the edge of annihilation; notion to which he would end up consecrating both his life and his death, settled in tradition – the samurai world equated both concepts, he insisted -, in his readings – like the French intellectual Georges Bataille – and, mainly, in the historical context of his childhood : The Belicist Japan Imperial who tried the vital perspectives of any young man towards the sacrifice in combat.

The echoes of this obsession resonate in initiatory in ‘confessions of a mask’. Despite his desire to become a kamikaze pilot to destructive glory of the emperor, when in February 1945 he underwent prior recognition suffered a cold that the doctor confused with tuberculosis. In the novel it narrates how the misunderstanding facilitates, until it is declared “not suitable for military service” and sent back home. His alter ego leaves the barracks to the race, exultant. Perhaps a repentance for life, perhaps an ephemeral moment of authenticity, perhaps both.

The fifties ended and the Japanese press already referred to Mishima as A ‘suppasuta’, a superstar. There was no more global artist, nor more Japanese. Now, that duality contained, in his opinion, a fierce ontological conflict. “The writers who know the Japanese language have come to an end,” he lamented in an interview. «From now on, we will no longer have authors who carry within your body the language of our classics. The future will be internationalism ».

That feeling of loss catalyzed its politicization process: a conservative reactionary, paladin of nostalgia that reacts combative to loss and, as such, a seducer archetype so many decades later. Mishima rejected subordination to the United States and the westernization of Japan, because he believed that capitalist materialism came to corrupt the ‘kokutai’, The homeland and its cultural tradition Specific. «Mishima began making political statements in the sixties. Until that moment he was had for an artist dedicated entirely to literature. For this reason, it seems unfortunate that even works prior to fifty have often been interpreted from an ideological perspective, ”says Saito.

The influence of fanaticism He began to take over his writing thereafter. In 1966, Mishima published ‘The voice of heroic spirits’a story that criticized the resignation of Emperor Hirohito to his divine condition, considering that he snatched the meaning of the immolation of the Kamikazes and other young soldiers during World War II. Two years later the theatrical piece premiered ‘My friend Hitler’which he interpreted himself, expression of his benevolent attitude towards fascism.

«Today his figure continues to raise questions. How could he profess those ideas and undertake those actions despite having been blessed with the greatest intellect and literary talent of his generation? ”Watanabe says. «Mishima found value in times of war, always full of tension and death, where the continuity of life was not guaranteed. He believed that the postwar period, acclaimed as a liberation of fascism, was on the contrary and despised him for having lost that tension. And with a simile, it resolves: «It could be called The Japan Cell».

It was 1968 and the hurried vital drama of Mishima began its outcome. In October of that year he founded the tatenokai, the society of the shielda private militia funded through its literary royalties and composed of a hundred university students with training in various physical disciplines. “The least armed and more spiritual army,” in charge of defending tradition. “There are two contradictory notes in Japanese identity: elegance and brutality,” he said of that. “After the war, the brutality has been hidden.” By then, the author already secretly prepared his final creation.

He November 25, 1970 Mishima left the house, leaving on the desktop the final page of ‘The corruption of an angel’, the fourth and last volume of ‘The Sea of Fertility’, its most ambitious literary project, an ideological testament on the Japanese cultural uniqueness, Almost two thousand pages covering from the Russian-Japonés conflict to their contemporaneity. All future commitments on their agenda had been canceled.

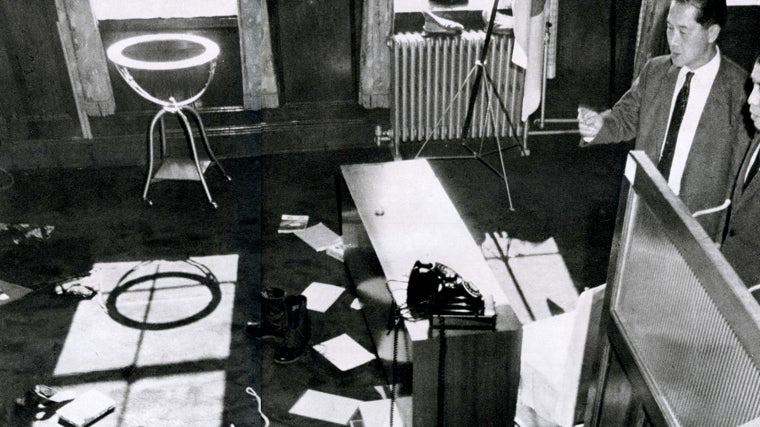

Office where they discovered the body of Mishima

ABC

Accompanied by four members of the Tatenokai, he went to the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Self -Defense Forces. Once inside they immobilized the commander. Mishima went out to the balcony, suddenly a stage, from where he called the troops to take arms against the Constitution to restore the emperor’s divinity. Some soldiers gathered in the courtyard ignored him, others made fun of him. “I think they haven’t heard me,” he muttered when he returned inside. Then, he knelt on the floor and drew the dagger.

His ‘harakiri’ It was a violent expression of the Japanese tradition that shocked a society given to the calm of pacifism and the market economy, completely alien to such atavisms. One of his biographers, John Nathan, ventured that the lifting attempt was nothing more than a pretext for ritual death with which Mishima had always dreamed. A work of art itself. Its elements had been in sight from the beginning, in ‘confessions of a mask’. Soldiers, blood, death. Glory. “Nothing happens if they don’t understand me immediately, Japan within fifty or one hundred years will understand me,” I used to ensure Mishima. His manifesto foreshadowed Japan’s rearmament. Does an increasingly hostile world end up giving, at least in part, the reason? “Unlike Western suicide, the ‘harakiri’ is an expression of pride,” he proclaimed in one of his last interviews. “Sometimes it makes you win.”

#Mishimas #controversial #life #death