“Short and neat hairstyle is the fashion favorite,” read the headline of one Vogue British magazine from 1923, based on a photograph of Dora Stroeva, the cabaret singer who wore loose-fitting suit jackets and her hair was slicked back. At the time, the publication was run by Madge Garland, the editor, and her partner, Dorothy Todd, the fashion editor. They published Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein and Vita Sackville-West and photographed women wearing the latest Chanel and Vionnet, and others wearing baggy trousers or white shirts, something that was quite common in the interwar period.

Five years later, Condé Nast fired them for “not fitting the image of the header”; the same year, 1928, in which the writer and friend of the couple, Radclyffe Hall, published The well of lonelinessnow considered the first novel with an openly lesbian plot. The British Government immediately banned it. In the fierce criticism that it published The Sunday Express In the book, the author appeared wearing a jacket, bow tie and monocle, a way of reinforcing the ‘inverted morality’ of which Hall was accused. This, obviously, amplified her legend, causing thousands of lesbian women to start dressing exactly like her.

“All our clothes mean something to the environment. Fashion serves to camouflage or to stand out when words fail. Many lesbians have always used fashion with that intention, although in very different ways,” explains fashion historian Eleanor Medhurst, who has just published Unsuitable (Hurst Publishers), a history of lesbian fashion, “because it has often been overlooked when we talk about the aesthetic of love,” she says. It is an investigation that has taken several years and that she has documented on her blog Dressing Dykes; from Christina of Sweden, the 17th century monarch who scandalized Europe by combining men’s and women’s clothing, to the present day, when the hashtag #Lesbianstyle on TikTok has 40 million posts. “This current explosion actually shows that there is not and has not been a single specific style, but rather a relationship with a complex and constantly evolving aesthetic; it is true that in the last two decades these styles have luckily been more visible,” explains Medhurst.

Until 2024, when Kristen Stewart parades around in military jackets over bras and tells prime-time host Seth Meyers that khakis and denim shirts “are kind of an old-fashioned thing,” lesbian women have had to dress to hide, to assert themselves, or to be recognized only by their community, and above all, they have had to fit in or oppose the aesthetic stereotypes that society has built around them.

Radclyffe Hall, Madge Garland, Anne Lister (who inspired the Gentleman Jack series) and all the women who in the 19th and early 20th centuries dared to show themselves as they were (that is, to mix outfits of both genders) because they could dare; they were all rich and/or aristocrats. The rest hid in clandestine clubs in Paris, Berlin or Harlem, where they gave free rein to their identity and, with it, to their aesthetics, either by reappropriating masculine clothes, reinforcing the idea of canonical femininity or mixing both, which in the 1940s became known as the butch-femme role (male and female lesbian), an archetype that, seen from the present, was a reflection of heteropatriarchal relationships, “but with a difference. In stable couples it was usually the femme who brought home the money, because the butch and her aesthetics made it difficult for her to have a career,” Medhurst says in her book. The butch-femme role Second Wave of Feminism, In the 1960s and 1970s, it gave rise to the “anti-fashion” movement, that is, the rejection of aesthetic impositions as a way of avoiding the male gaze. A uniform of combat boots, jeans, short hair and no makeup or bras (very similar to what, 50 years later, Seth Meyers described to Stewart on his show as “the uniform of a lesbian icon”): “It was not a typically masculine wardrobe, but rather androgynous. The goal was to achieve ‘ugliness’, something that women have been taught to avoid at all costs,” explains Medhurst, “in this way they were freed from aesthetic pressure and male judgment, and could be themselves.” If at the beginning of the century Madge Garland used the ‘excuse’ that “women’s things were fun frivolities” to break prejudices from the pages of Vogue, 50 years later lesbians flatly

rejected fashion for being frivolous and they did so, paradoxically, for the same reason: to break with heteropatriarchal conventions.

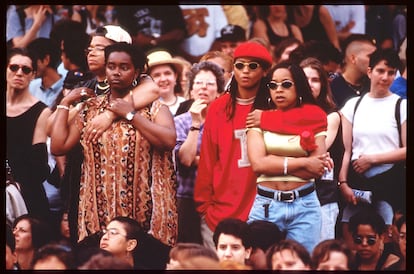

But, like any identity aesthetic on the margins, came the ‘stylization’ of lesbians by the media. In 1993, singer KD Lang appeared on the cover of New York Magazine with the headline Lesbian Chic: The Brave World of Gay Women; weeks later he starred in the Vanity Fair alongside Cindy Crawford. The singer wore a suit and the model, a swimsuit. “A media aesthetic that featured powerful, white lesbian women with highly qualified professions, wearing perfectly cut suits,” writes Medhurst. “It was not a positive fashion, because it only reflected a type of lesbian promoted by the media,” she tells this magazine. Only 20 years passed between those covers and the series The L worldwhich took this concept to an extreme completely removed from reality. So is fashion itself, where, despite the capitalization of this archetype, there is still no famous openly lesbian designer (not their case). “We are entering the happy era of lesbian fashion,” was the headline. The New York Timesreferring to those celebrities who display their identity through an intentional mix of sensual and utilitarian garments, trying to transcend binary wardrobes. The problem, perhaps, is that lesbian fashion, an identity tool, cannot (or should not) be turned into a temporary uniform, that is, into just another fashion. “I think that we are finally talking about an aesthetic of authenticity, beyond styles or stereotypes,” says the historian, “fashion has always been opportunistic, and has often used queerness for its own benefit. It is the community that creates the style with its clothing choices.”

#overalls #lipstick #lesbians #claimed #aesthetics #fashion