The memory of Denver nine months ago seems out of this world. In mid-January 2024, the capital of the state of Colorado reached its peak occupancy in the makeshift temporary migrant shelters, with 5,200 people, almost all asylum seekers sent by bus from Texas by Governor Greg Abbott, sleeping in hotel rooms paid for by the city. On the streets, entire families, already expelled from the shelter system for reaching the maximum time in the system, were reported to be spending the freezing winter nights at the foot of the Rocky Mountains under bridges and waiting for hours to get a hot meal.

Mayor Mike Johnston, with the city’s accounts in the red, asked the federal government for help several times. There was no response. Faced with silence and a municipal expenditure of 72 million dollars since the end of 2022, to care for a total of 42,000 migrants, he and his team decided that something had to change. They devised a new program, focused on long-term integration.

In the spring, while Chicago and New York were announcing new, stricter time limits for staying in shelters, Denver proposed something almost the opposite: full and continuous support for six months, the time it takes to approve an asylum application and obtain a work permit. Now, with the new program in operation since late June and at full capacity, with 865 beneficiaries, including 215 families, and also with new migrant arrivals at a minimum due to the implementation of Joe Biden’s executive order to limit illegal border crossings, the city is different.

Sarah Plastino, director of the new program, explains that “the goal of the program came from the fact that a large number of people were leaving shelters and entering our communities here in Denver at the same time.” “We knew we needed a program that would specifically support those people who did not yet qualify for a work permit and needed to apply for asylum. So we designed this to capitalize on the six-month waiting period to train those who were waiting for their work permit and provide a large number of people with stability.”

First, they decided that instead of housing people and families in hotel rooms night after night, which would be extremely expensive, they would be placed in permanent housing for six months. This is cheaper for the city, but it also gives the beneficiaries more autonomy. In partnership with non-governmental organizations, they assigned apartments and houses available on the regular market, according to the size of the families and the area where the children were already attending school. Using the same logic, they began to provide food and vouchers to prepare meals at home, which is also much more economically efficient for the city than providing food through restaurants or contractors. Also, to make it easier for them to move around and communicate, those who have joined the program have been given mobile phones, SIM cards and public transport passes.

These foundations provide stability in the present and generate a very different relationship with the authorities. Plastino tells the recent anecdote of how he put a migrant in contact with the police who needed help with a delicate security issue. “She probably wouldn’t have felt comfortable enough to trust me and then talk to the police,” he reflects.

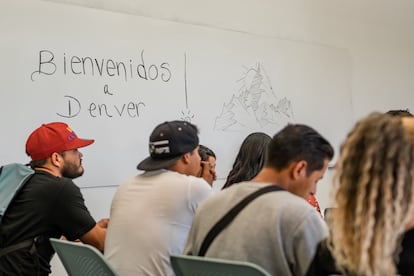

But the program has a long-term vision above all. While minors are legally enrolled in school from the moment they arrive, adults had to wait six months with their arms crossed while they received a work permit, since they had no resources and no legal way to generate them. Now, under the program and in alliance with the Workers’ Center, a non-state organization in the city that is dedicated to the training and professional development of the working class, they offer English classes for migrants and also job training in the areas where there is the greatest demand for employment: construction, hospitality and care. In addition, in direct contact with potential employers, it is expected that they will get good jobs as soon as they have authorization.

This was already something the Workers’ Center did independently, but by collaborating with the city the operation has grown immensely, says Mayra Juárez-Denis, executive director of the organization. “The city saw what we had done and was very impressed. We had limited resources… Now they refer these participants to us and it’s like the same program we were running, but on steroids, because we have twice as many resources, more collaborators and interest from companies, which are in contact with the city’s Department of Economy, to find jobs for people beforehand. That collaboration is very powerful.”

They are committed to training at least 500 people this year. The plan has several distinct stages. The first, which is now ending, focuses on the basics, mainly English, computer and cultural classes, to facilitate assimilation into a new society. The second, which is just beginning, is the vocational stage, aimed at preparing immigrants for the jobs that are available.

As an immigrant from Monterrey, Mexico, Juárez-Denis hopes that this program will demonstrate “the power of our institutions, not just government institutions, responding to the needs of the community.” She maintains that this way, a chain of solidarity and support is cultivated that strengthens the social fabric. She has already seen this in action: a family of migrants who “literally arrived with a backpack” and now, after finding employment, can also teach others.

For Sarah Plastino, the program is a source of pride after months of hard work to make it a reality. “It is designed to benefit the individual, but also industries where there is a shortage of workers. It is very strategic,” she says, adding that she would like to make it a model to follow by showing that even on a smaller scale it is possible to provide effective solutions to complicated problems.

However, the basis for the program’s success for now depends on border crossings remaining very low and, therefore, new arrivals in Denver being practically frozen. Throughout the months of July and August, Texas did not send any buses with migrants to sanctuary cities and only a handful of new immigrants arrived in the capital of Colorado who are being served with a basic reception program that provides shelter and food; but for only a few days before facilitating their transfer to where they can be received by relatives or friends.

In the event that migrant arrivals spike again, Plastino says they are prepared and have redesigned the reception system based on lessons learned during the most critical period, although she does not provide details. In any case, the most important lesson is that one must be flexible and adapt to the specific needs of each moment, stresses the director of the program. In the current context, that means a comprehensive and long-term support program to facilitate the social and labor integration of the nearly one thousand migrants who now call Denver their home.

#roof #English #job #training #Denver #offers #model #integration #migrants