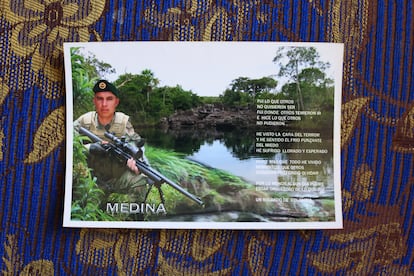

“Honey, we are here in Caracas.” A map with the geolocation of Maiquetía International Airport, where he was stopping over on his way back to Colombia after having fought for several months in Ukraine, that brief WhatsApp message and a three-minute video call that ended abruptly on July 18 at 5:30 p.m. were the last things Cielo Paz heard from her husband, José Arón Medina, during the six long weeks he was missing. It was not until August 30 that she heard from her husband again, when she identified him in a video released by the Russian Federal Security Service, the former KGB. Together with his partner Alexander Ante, another former Colombian soldier from the Cauca department who fought in the Ukrainian army, they were arrested and a Moscow court accuses them of being mercenaries, which could lead to 15 years in prison.

What exactly happened in those six weeks, when and how they traveled the almost 10,000 kilometers that separate Caracas from Moscow, remain loose ends due to the secrecy of the Venezuelan authorities. Their relatives have not received answers, and their actions at the Venezuelan embassy in Bogotá were ignored. Ten days after their disappearance, on July 28, Venezuela held the presidential elections of which Nicolás Maduro has declared himself the winner without showing any credible evidence of that result. Russia is one of the few countries that has recognized Maduro’s reelection. It was also a financial lifeline when the United States sanctions blockade complicated the commercialization of Venezuelan crude oil, so Hugo Chávez’s heir has responded with vocal support to Moscow regarding the invasion of Ukraine.

The Maiquetía airport has become a black hole in which Venezuelan intelligence services operate with total freedom, a risky transit site where they have already made several arrests in the last year. The apparent extradition of the Colombians has been surrounded by mystery. Both the Attorney General of the Nation, Tarek William Saab, and the new Minister of Interior and Justice, Diosdado Cabello, have referred to the case of an American soldier detained in Venezuela a few days ago, but they have not said a single word about the Colombians, an episode that could affect relations between Bogotá and Caracas at a particularly delicate moment, when President Gustavo Petro insists on mediating to achieve a negotiated solution to the post-electoral crisis. In response to the formal request for information made by Colombia through diplomatic channels, the Venezuelan Foreign Ministry responded that it had registered their entry on July 18, and was not aware that they were detained in Venezuela.

Mediana and Ante belonged to the Colombian Army. Afterwards, they spent several years dedicated to security work in Popayán, the capital of Cauca, one of the departments hardest hit by the armed conflict. In a telephone conversation with this newspaper, his wife describes José Arón Medina, before any other trait, as an excellent father. They have two children, one 16 years old and the other nine. “He really likes the army,” she says, recalling that he was a professional soldier for four years. Since then, 15 years ago, he worked as a security guard until he accepted an attractive financial offer to go to Ukraine, where he earned 12 million pesos a month (about 3,000 dollars). He left in November and spent eight months in the war, until he decided to retire. “He said that he had already seen many comrades die and he was not going to risk his life any more, so he decided to go back home, but they never came,” laments Cielo Paz.

Newsletter

Analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your inbox

RECEIVE IT

The woman received the video thanks to Medina’s comrades in arms who are still in Ukraine, and that is how the family found out that he had reappeared in Moscow, along with Ante. The Prosecutor’s Office had even published their posters as missing. “We did not receive a single call from Caracas, we did not know what had happened, if they were alive or dead; they were distressing days, and until now we have had no communication with them,” she says. On Tuesday, she received a call from the Colombian consulate in Moscow to inform her that they would have a public defender. She asks the Foreign Ministry to help them return to Colombia.

Alexander Ante, 47 years old and father of a five-year-old girl, had also retired from the Army for nearly two decades, after 13 years in service, and was a bodyguard in Cauca, says his brother River Arbey. “They went to serve directly with the Ukrainian army,” at the invitation of President Volodymyr Zelensky, he stresses. His brother left Ukraine after eight months, with his head held high and with the doors open for whenever he wanted to return, he maintains. “They are not mercenaries, as they are labelled; mercenaries are those hired by private companies,” he stresses.

er Ante’s military beret and scarf preserved by his mother.ANDRES GALEANO

In the video that was released in Russia, both men identify themselves as members of the 49th Infantry Battalion, called the Carpathian Sich. The soldiers of the 49th battalion, many of them foreigners, have fought on the toughest fronts. At times, the unit has been greatly diminished, particularly in the European winter at the end of last year. Some of its fighters have abandoned the front in the face of the harshness of war. “For a long time, it was the flagship battalion where Colombians fought, alongside the international legion,” confirms by telephone Colombian journalist Catalina Gómez Ángel, who has been deployed for long periods as a war correspondent in Ukraine. She is currently working on a documentary about Colombians on the front, most of whom are former soldiers who worked in security duties. “They tend to be relatively young people; many of them, in addition to money, miss their military life,” she says about their motivations.

The Colombian presence has been noticeable for some time. With the Ukrainian ranks decimated by the rigors of war, they welcome without hesitation these combatants hardened in one of the longest armed conflicts in the world. With some 250,000 troops, Colombia has the second largest army in Latin America, after Brazil. More than 10,000 are retired every year. After President Zelensky’s explicit invitation in February of this year, they have been recruited through WhatsApp groups of ex-military personnel, but also through videos on social networks. They arrive in the country at war on their own, like other Latin Americans. They enter from Poland, cross by land into Ukraine, which keeps its airspace closed, pass through a recruitment center and cross the country to a front in the east. That explains the striking Warsaw-Madrid-Caracas-Bogotá-Cali itinerary that Medina and Ante bought for their return, without realizing that showing up at Maiquetía in the Ukrainian military uniform would expose them.

Although the Colombian Foreign Ministry has not made a public statement regarding the two former soldiers presumably extradited to Russia by Venezuela, it has raised the alarm regarding national combatants in general. Neither Ukraine nor Colombia offer concrete figures on how many Colombians are fighting this war, but the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has acknowledged that at least fifty have died in the last two years. It has also recently reiterated that “the Colombian Government does not promote or facilitate the involvement of Colombian citizens in the Ukrainian army. These personal decisions are completely voluntary and individual.” The ambassador to the United Kingdom, former senator Roy Barreras, even warned in June that “those who leave with the hope of earning money for their families are dropping dead like flies. What they are paid is not even enough for the repatriation of their corpses. So they are being used as cannon fodder.”

International law is ambiguous about the legality of foreign participation such as that of the Colombians in a war like the one in Ukraine. The Colombian Foreign Ministry and the Ministry of Defense have just submitted a bill to the Congress of the Republic seeking approval of the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries. In other words, they are seeking a formal ban on mercenarism in Colombia, although it is not entirely clear that those who go to Ukraine fall into that category, since they fight in a regular army, with payments and benefits similar to those of Ukrainian citizens. kyiv considers them legal combatants. Russian legislation, for its part, considers mercenaries illegal, but at the same time it is one of the countries that most relies on private companies and foreign combatants.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and Here on the WhatsApp channeland receive all the key information on current events in the country.

#drama #Colombian #soldiers #detained #Russia #stopover #Caracas #mercenaries