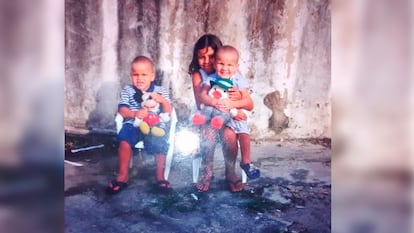

Jesiel Viana is an engineer software A 34-year-old Brazilian who has no photos of his childhood. At that time there were no cell phones, his family was very poor and everything was far away. He grew up in Inhame (Piauí), a small town in the interior of the most arid and needy Brazil. Electricity only arrived this century, when he was 15 years old. Son of farmers —a mother who can read and write and an illiterate father—, Viana belongs to the first generation of children of Bolsa Familia, the program that lifted 25 million Brazilians out of poverty, alleviated hunger, improved health… That small monthly aid —about 144 reals today, 25 dollars or 23 euros— changed the destiny of this family with three children who grew beans and manioc. They barely survived with the minimum and with loans at usurious prices. That kid who saw his first computer at 18, earned a master’s degree in Software Engineering and is a teacher. His case may seem exceptional but it is not so, as an academic study has just certified.

Researchers have found that 64% of the first generation of Bolsa Familia children are adults who no longer need public assistance, breaking the cycle of poverty that often trapped their families for centuries. And half of them have found some formal employment, according to the study. Social mobility and CCT programs: The Bolsa Família program in Brazil (Social Mobility and Cash Transfer Programs: The Bolsa Familia Program in Brazil), published in the journal World Development Perspectives (World Development Prospects). The authors followed beneficiaries aged 7 to 16 between 2005 and 2019 to check whether they still needed the state for basic needs as adults.

The Bolsa Familia, created by Fernando Henrique Cardoso and expanded by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is known as one of the most effective and cheapest anti-poverty programs in the world. Despite its success, 21 million households still need this monthly payment — the emblem of the Workers’ Party’s social policy — the amount of which has increased fivefold since the pandemic.

“The program has positive long-term effects, they are unanticipated effects. Nobody thought about that when Bolsa Familia was created,” he explained to the newspaper. Economic Value One of the authors of the study, Paulo Tafner, director of the Mobility and Social Development Institute, argues that the success lies in the fact that Bolsa Familia imposes two trade-offs: it is mandatory for children to go to school and be vaccinated. Thanks to this, several generations continued studying without having to work to help the family economy.

Over the years, the state has benefited from this, according to the study cited above. These children contribute to the public coffers with their taxes. A virtuous circle was created, which, however, did not overcome inequalities. Bolsa Familia worked better among men, whites and the most prosperous regions.

Like Viana, millions of Brazilians have conquered—thanks to public aid and taking advantage of every opportunity—a life that was unimaginable when they were children. These are the stories of four of them: a computer engineer who grew up without electricity in Piauí; a psychologist and successful businesswoman who started working at 14, later than her siblings; a cardiologist’s assistant who at 13 shared a single pair of sneakers with a brother; and an English and Portuguese teacher raised by a widowed grandmother who once a month managed to give her a treat, some filled cookies paid for on credit.

Aline Nogueira dos Santos, 34 years old, Rio. Teacher of English and Portuguese

“My grandmother raised me and my two brothers,” she begins on the phone. “She was an illiterate widow with a minimal pension, but despite all the difficulties she did not let us lack anything basic. Bolsa Familia was not a matter of survival for us, as it was for others, but it brought us a certain dignity,” says this Rio de Janeiro native who teaches languages in two private schools. With the help, she was able to provide them with moments of happiness in the midst of that precariousness. Bolsa Familia meant making a special plan, going to the park, a toy. Maybe getting new clothes for Christmas. And a little treat from time to time. “At that time there were street vendors who sold door to door a kit of filled cookies, or yogurt, and you paid the following month.”

At 18, Dos Santos had his first formal job. And at 24, he entered university thanks to a loan of which he has only two installments left to pay.

Graciane Barbosa, 31 years old, Chopizinho (Paraná), psychologist

“I always say that I am a child of public policies,” says Barbosa, the youngest of three siblings raised by a single mother who worked all her life in general services and for a couple of years needed Bolsa Familia. With that, in that difficult phase, they were able to buy school supplies or eat meat sometimes. The little girl’s destiny began to change in third or fourth grade, when she entered a program to eradicate child labor. It worked. At 14, she earned money as a babysitter and studied at night, but it was a huge improvement compared to her siblings: the eldest worked from the age of 9, the middle one at 11. “That program became a refuge. I did karate, theater, drawing, tutoring, literature… It broadened my horizons, gave me a repertoire for life.”

Barbosa teaches at the university and works as a psychologist with autistic children in the thriving practice she created. She is a proud contributor. Daughter of founders of the Landless Workers Movement, she says: “If I want to make a very liberal analysis, I will say that I contribute 20,000 reais a month.” [3.500 dólares] in corporate tax to the public coffers.” He hopes that this money will serve to provide opportunities to those who need them.

She explains that when Lula came to power in 2003, families like hers no longer felt helpless. Their lives changed. Her mother, married at 14 and a mother at 16, fulfilled her dream (with public assistance) of buying a house made of brick, tiles and a decent bathroom. “And I have a life I never dreamed of. My own house, a car, a doctorate…”

Samuel Zanetti Barreto, 38, Viamão (Río Grande do Sul). cardiologist assistant

The eldest of five siblings, things were going well enough in the family for everyone to attend private schools until everything went wrong. His father became unemployed and his accounts were seized. “Those were very difficult years,” he says. First, everyone went to public school. Then, his mother and older siblings did what every Brazilian family does when they lose their income: sell empanadas or sweets on the street. “Bolsa Familia was essential,” a lifeline, because, although his father found a job, it was not enough to support the seven of them.

Zanetti, who was always a good student and works as a technician in artificial cardiac stimulation, gives a very clear example to illustrate what it means to be poor. “When I was 13, my brother and I studied in separate shifts. People thought it was strange. We only had one pair of trainers for the two of us. And, of course, you feel ashamed.” Added to the material shortage was marginalisation due to sheer ignorance. Although they had a small library at home, they lived for years without documentation or access to banks. The support of other evangelicals was crucial, he adds.

When the eldest son received a scholarship to university and a paid internship, the family began to dig itself out of the hole. He and his four siblings built life plans and emancipated themselves from the state.

Jesiel Viana, 34 years old, Inhuma (Piauí). Software Engineer

He grew up far from almost everything, with almost nothing in a farming town. At 11 years old, the boy who became a computer programmer software He worked the land and traveled 30 kilometers every night to go to school. The eldest of three, at 12 years old he had his first long pants – a pair of jeans—. They ate meat at most once a week or when they hunted some wild animal. Bolsa Familia, which her mother received for more than a decade, was essential because even with that they were in dire straits. “We lived with the minimum, my parents didn’t spend anything, they are evangelicals.”

At 18, Viana moved to another galaxy, to Brasilia, to stay with an uncle. There he saw the first computer of his life. He worked at a gas station to save up before going to university thanks to a scholarship. He remembers that he enrolled in computer science because “the cost of the material was zero.” At first he was completely lost. “I didn’t understand even the most basic concepts, but I was embarrassed to ask,” but he always had the conviction that he would succeed and enormous self-confidence. After earning a very good living for a few years in the capital as a computer engineer, he wanted to return home, to Piauí, one of the states where the most families receive Bolsa Familia. He took an exam and got a teaching position at a federal high school where the students believe he is joking when he tells them that he grew up nearby in enormous hardships. Without electricity, a computer or photos.

Shortages persist. Sometimes a student is taken home to have lunch with his family because otherwise he would go hungry.

Follow all the information from El PAÍS América on Facebook and Xor in our weekly newsletter.

#Bolsa #Familia #children #inherit #poverty #Brazil