Once again, the story is repeated. The east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (RDC) is once again the scene of violence and suffering. From the Rwanda genocide in 1994, when around 800,000 tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed in just 100 … Days for Hutus extremists, the region has not known peace. The fall of Kigali in the hands of the Ruandés Patriotic Front (FPR), led by Paul Kagame, ended the massacre, but not to the ethnic tensions that continue to mark the fate of the great lakes.

Since then, the conflict between Tutsis and Hutus has served as a catalyst for an endless war in the east of the Congo. The region has become a chess board where rival militias justify their violence with the defense of one or another community. In the epicenter of the crisis is the rebel group M23, mostly composed of Congolese tutsis and backed by the Rwanda government.

Lifeless bodies lie in the streets of Kiwanya after the 2008 massacre, when the fighting between the CNDP and the government forces turned this community into a death field. In the midst of chaos, civilians were trapped without the possibility of fleeing, paying the price of a war that did not belong to them. The scene, captured then, remains a reminder that in the east of Congo violence is not an isolated episode, but a constant that is repeated with different names but with the same victims

The M23 did not arise from nothing. He is a direct heir of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), an armed group led by Laurent Nkunda, a former Tutsi exophsi of the Congolese army that became one of the most feared and enigmatic figures of the conflict. Nkunda, known for his messianic speech and his self -proclaimed mission to protect tutsis in the east of the Congo, directed the CNDP with a combination of brutality and salvationist rhetoric, justifying their attacks as a fight against discrimination of their community.

His moment of greatest notoriety came in 2008, when his troops launched a fulminant offensive that took them to the rubber doors, the capital of Kivu del Norte. In a demonstration of power, the CNDP defeated the Congolese army easily, leaving the city on the verge of collapse. However, instead of occupying rubber, Nkunda opted for a different strategy: he pressed the international community and negotiated from a position of force. The offensive unleashed a humanitarian and diplomatic crisis, forcing the United Nations and the region to intervene.

But his boom was brief. In 2009, Rwanda, his main ally until then, turned his back. In an unexpected turn, the Ruandés army, in a joint operation with the Congolese forces, captured Nkunda in Rwanda and put him under house arrest, ending his military reign. The CNDP was dismantled, but its combatants were absorbed by the Congolese army in a fragile agreement that only postponed the conflict.

In 2012, a group of CNDP ex -combatants defected from the Congolese army, claiming the breach of the integration agreements signed in 2009. They made the call March 23 (M23), in reference to the date on which Kinshasa allegedly had complied with its promise of recognition and autonomy for the Congolese tutsis in Kivu del Norte. The story was repeated again: the M23, with the silent support of Rwanda, launched a fulminant offensive and took rubber in November 2012, humiliating once again a Congolese army unable to contain its progress.

Accused of war crimes and mass violations. In the east of the Congo, the brutality against the civilian population has been a recurring war strategy, where sexual violence and massacres have become weapons for the control of the territory. His capture is a rare exception in a conflict marked by impunity, where the victims are still waiting for justice while the war continues their course.

Álvaro Ybarra Zavala

The occupation of the city only lasted eleven days, but it was enough to leave an indelible brand in the memory of the population and in regional geopolitics. The international pressure, headed by the UN and the East African community, forced the M23 to retire, and in 2013 the group was officially defeated after an offensive of the Congolese army backed by a special United Nations intervention force. Its leaders fled to Rwanda and Uganda, and for almost a decade the M23 disappeared from the battlefield.

But the conflict never really ended. In November 2021, the M23 resurfaced from the shadows, better trained, better armed and with a combat capacity that surprised both Kinshasa and the international community. In less than two years, the group has made significant strategic advances, taking control of vast territories in Kivu del Norte and approaching dangerously, once again, rubber.

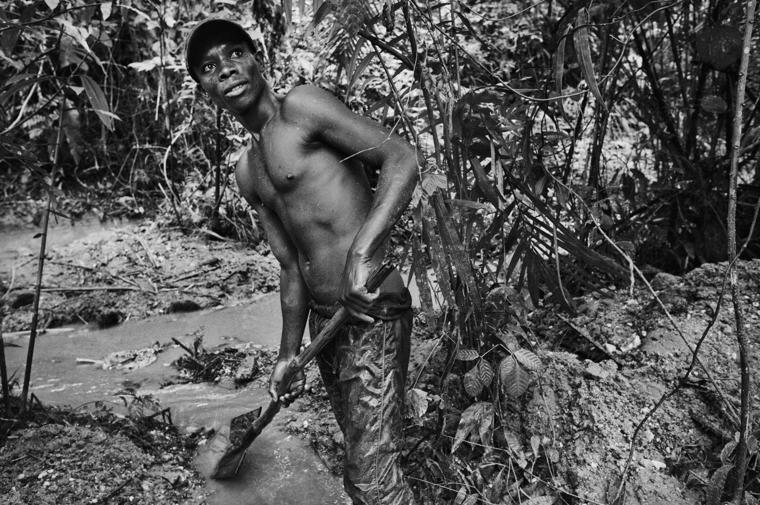

With the hands covered with mud and sweat, an illegal miner excavates in search of Coltán on the outskirts of rubber, in the heart of Kivu del Norte. Extracted in extreme and regulation conditions, this key mineral for the global technology industry feeds not only the black market, but also war. Armed groups such as M23 have turned mining exploitation into one of their main sources of financing, controlling and looting these deposits to sustain their fight. In the east of the Congo, the violence and mineral wealth go hand in hand, turning the subsoil into the true trench of the conflict

Álvaro Ybarra Zavala

In the center of this new offensive is Sultani Makenga, the M23 military commander, a veteran of the Congo wars who already led the 2012 offensive. Makenga is a man of war, tanned in combat and with direct connections with Kigali. Beside him, in the political sphere, Bertrand Bisimwa has become the visible face of the movement, trying to present it as a legitimate actor in the unstable policy of the region.

But behind ethnic speeches and protection promises for Congolese tutsis, the true battle is not because of identity, but for the control of resources. The east of the Congo is one of the richest regions in the world in strategic minerals such as coltan, gold and cobalt, essential for the global technology industry. Rwanda has been indicated in multiple UN reports for its participation in the looting of these resources, and the M23 is nothing more than another tool in this silent war for the control of the Congolese subsoil.

#war #inheritance