You do not know the tradition of the Three Wise Men in Spain well if you have never seen their majesties huddled on top of a field tractor, well wrapped in patent leather paper for the occasion, while they wave with one hand and try not to fall with their hands. other. This image, which to someone might seem intolerably tacky, was pure fascination and magic for several generations. And still today their majesties huddle in patent-leather tractors in many parts of the country, greeting the nervous and invariably fascinated kids. The success of a traditional fantasy like horseback riding has not so much to do with fidelity to a single model of representation (crowned men on camels in bright robes), or even with fidelity to the memory of that representation that we saw in our childhood, but rather that really draws on what we hope to feel, on the ability to create an atmosphere of fascination and magic that accompanies that feeling that anything is possible while we wait for our gifts. And that is achieved in many different ways.

In recent years we have argued heatedly about how a successful recreation of the Three Wise Men tradition can be affected by issues such as the presence of wizard queens, the fashion trends their majesties must follow, whether live animals are appropriate or not, or what Baltasar should look like, and what the political implications of that particular face are. Many of these issues have been discussed in terms of the “authenticity” of the tradition, understood as fidelity to a supposedly shared model of representation, but that model was never such. The first historical representations of the wise men that Matthew mentions in his gospel show three white men on foot wearing hose and knee-length skirts, short capes, and caps instead of crowns or turbans. They are shown this way because that was considered a recognizably “oriental” way of dressing in Europe. If then the kings had been painted long cloaks with an ermine and a crown, or a black Baltasar with a turban (elements that today we consider the quintessence of the tradition), the people of the time would have considered it absurd that the portal of Bethlehem was visited by a desert nomad and a couple of European kings. What today is a satisfactory story in our society would be a tremendous nonsense for our ancestors.

The definitive transformation of those Zoroastrian priests from Persia (that is what the word “magi” means in the Bible) into the Three Wise Men of the European tradition occurred during the Renaissance. That was a time of many cultural, political, and religious changes, and of many resistances to those changes, as it seems to be the case today. Renaissance painters made the worship of the magi a fashionable subject and began to experiment with their representation. Although some iconographic elements were earlier, the representation of the magi as kings with European crowns combined with orientalizing details that gave a certain image of exotic luxury was consolidated, the capes became longer and the theme of the three ages was deepened: the white beard represented senescence, the brown one middle age, and the beardless king would represent youth. The differentiated skin coloring, and its interpretation as different ethnic origins, would later be consolidated with colonial expansion starting in the 16th century, until it forms the contemporary narrative. But what about the tractors?

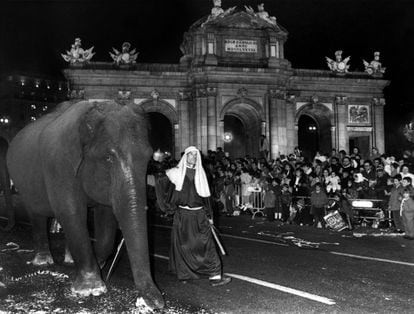

Popular culture underwent a radical transformation with industrialization and capitalism, and this affected one of its favorite expressions: horseback riding. Although today we imagine the scene of the Three Wise Men in our minds as an orientalist fantasy that evokes a family past of a certain elegance, at least since the 19th century the parades have become a peculiar technological and advertising exhibition. From early on, motor vehicles were incorporated into them, which over time displaced horses, mules and donkeys. And they wouldn't just ride tractors or cars. Their Majesties would ride motorcycles at various times in the 1950s and 1960s, advertising Vespa and escorted by bullfighters and pages dressed as robots.

On other occasions they would wave from the blades of huge, decorated excavators, from motorboats and from helicopters, depending on the location and who was financing the affair. As the space race was a topic present in the society of the sixties and seventies, space rockets were also represented in the parades, while the Kings were escorted by astronauts. Those cute astronauts mixed with scooters, bullfighters and excavators effectively excited the fascination of young and old people with technology and a promising future for the country, an emotion that ultimately fits with the original scene of worship, in which Some Persian magicians bet on a Jewish child who has just been born, but who would later change history.

Recreating magic, illusion and optimism cannot be done today as it was then, nor then as in the previous century. The things that move us are other. Today, cinematographic characters abound and the emotional and magical success of the parades is not linked to traditionalist purism (which is a fantasy in itself) but to the presence of characters from Hollywood, video games and even drag queen and other current fantasies that at this moment have the ability to recreate a surreal and prodigious night, which transports children's minds to a fascinating and promising magical world, like the one that space rockets made of painted cardboard and aluminum foil evoked for me. The traditions that survive are those that are transformed.

One day the parades will be led by people whose gender will be peacefully irrelevant to the magic of childhood illusion. Of course, we will not expect their faces to be as they are now to be believable, and perhaps in the future it could become realistic that there were 12 again, as in the origins of the tradition, instead of three as they are now. Perhaps their majesties will become artificial intelligences so that we can fully experience the fascination of the magic of the future, and perhaps they will not even be anthropomorphic. They will parade in vehicles not yet invented and will represent the values of a society different from the current one, whate

ver they may be. Those of us who live now may see it as ridiculous, but those who live it in their time will be enjoying their own sense of tradition, and their own fascination with the wonder.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#Wise #Men #magic #traditionalist #purism