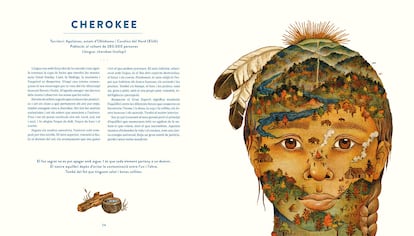

Igloolik is a tiny island northeast of Canada. His name, in the local language (inuktikut), It means “it has houses.” Not many, actually: either because of the location, near the Arctic; because of the extension, which can be walked from one end to the other on foot in less than five hours, according to Google Maps; or because of the climate, with temperatures that almost never exceed seven degrees and can drop to 30 below zero. Aviaq Ginny Mary Pavvik Akumalik Berthe Johnston grew up in one of those homes. Or, as it is also presented, Aviaq Johnston.

Easier for most of the public. The same filter that the young Inuit author initially applied to her texts. “I come from a very isolated part of the world. But what I read was very Western, so my writing reflected that. “I built plots in big cities, with characters I had never met in my life,” he said a few weeks ago at the Bologna Children’s and Youth Book Fair, the most important in the sector, where he went to explain how he became aware of his roots. And to vindicate a movement that has grown tired of being silenced. Many indigenous communities had their land stolen. Then, the language and the voice. Finally, the future. So the time has come for them to tell his stories. And in his way.

“Every child has the right to hear their story in their own language,” defended Victor DO Santos, children’s author and Brazilian linguist, in the same conference, titled Origins: indigenous voices in books for young people. Something obvious for any white kid from the first world, used to starring in almost all the novels, movies, songs or video games that surround him. Less common for the other half of the planet. Rare, for any small member of minority, marginalized or even discriminated groups. Or for those who have special needs. And practically impossible for the indigenous people.

So much so that, when little Noemí finally had the opportunity, “she didn’t stop reading.” The memory is by Adolfo Córdova, author of the first children’s book published in the nuntajiiyi that is only spoken by a few tens of thousands of inhabitants in the Mexican Sierra de Santa Martha. Among them, Naomi. And his teacher, Emmanuel Rodríguez, who helped the author to translate Jomshuk, Child and Corn God (Castle), based on the ancient local legend of a boy born in the jungle, capable of avoiding all kinds of dangers and even death thanks to the help of animals. “Not even books offered Naomi a personal refuge. If anything, a foreign home. But it is not enough to bring other works to these languages. You have to look for those that are originally written in those languages. And if they do not exist, you have to write them down,” Córdova pointed out.

The story of Michel Jean’s great-grandmother is not yet published in innu-aimun. Although the author, a member of the Innu, in Quebec, assures by phone that he is working on it. Meanwhile, Kukum (Paper Times) has conquered thousands of young and adult readers around the planet with the true story of a woman who falls in love with an indigenous man and embraces his lifestyle. But, at the same time, the novel tells another true story. And not at all idyllic. “Today everyone is worried about the end of the world. These communities have tried it, they have seen how theirs disappeared and were forced to accept another, which they never chose,” says Jean. Because, for almost a century, Canada locked indigenous children in so-called “residential schools”, boarding schools where their identity, their language and, sometimes, even their very existence was broken. “What happened still has consequences. Today we represent 2% of the population but 30% of the homeless. Thousands of young people were forcibly taken and displaced hundreds of kilometers. If you were the 22nd to get off the plane, you were already called with that number. You were punished if you spoke your language,” Jean explains. An estimated 5,000 never returned home. Including a cousin of the author’s mother.

That is why Jean believes that his novel is also “a declaration of intentions”: “No one was interested in our story. An editor told me: ‘If you don’t tell it, who will? It is our responsibility. It doesn’t mean that others can’t, but it does mean that we are the ones who know it the most and are in the best place to understand it, and tell it.” In Bologna, Aviaq Johnston wanted to start his intervention in inuktikut. And he has published his first young adult novel, Those Who Run in the Sky (Those Who Run in the Sky), in 2017, both in English and your home language. Screams previously isolated that now come together to make more and more noise. “It is a recent phenomenon of representation of those who did not have it, with different degrees depending on the countries. The circulation of these books, which would hardly have been disseminated beyond their market, is also important to put an end to folkloristic and stereotyped visions,” he highlighted. Dolores Prades, editor and director of the Emilia Institutededicated to spreading the love of literature, and coordinator in Brazil of the Latin American and Caribbean Chair of Reading and Writing.

Something similar is happening with Maori, ‘ōlelo, Mapuche or Kriol. “What happened in Quebec is the same as in South America, Africa or with the Sami, in Scandinavia,” Jean reflects. Or in Australia, dwhere the Indigenous Literacy Foundation not only brings English books to the most remote Aboriginal communities. She also tries to foster her reading passion with daily sessions. And it promotes the edition of children’s and youth stories rooted in the territory, and told in their languages. “There are children who speak four or five. English may be sixth. And yet it is the one they find at school,” he reflected. Nicola Robinson, from the foundation, in Bologna. Where she collected on behalf of her entity the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, the largest in children’s publishing, in recognition of her 13-year work that has brought more than 750,000 books to some 400 communities and published 109 works in native languages.

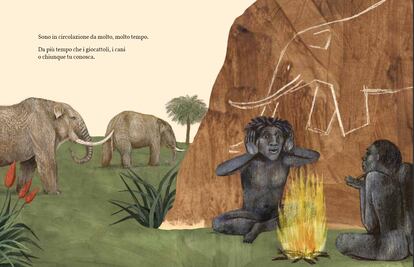

“What does ‘indigenous representation’ mean? Is it okay to talk about these topics without the authors and illustrators belonging to those communities? And books by indigenous creators, but on other topics? Or works in native languages, but carried out in another place, far from the town?”, Santos questioned in Bologna. And he remembered that a statement unanimously approved by UNESCO in 2001 raised cultural diversity to the level of “common heritage of humanity”, as “necessary as biodiversity for nature”. The writer has also emphasized it lately as he knows best: with a book. His last work, The most precious thing (illustrated by Anna Forlati, Terre di Mezzo), celebrates the importance of languages. “You can find me anywhere. In every nation, city, school or home,” its pages read.

“There are 364 languages in Mexico. But today only 6% of the population speaks them. The dominant languages have been responsible for marginalizing them,” Córdova attacked. Here is language as a weapon and legacy of colonialism. “We are 11 indigenous communities in Quebec and only one language is recognized by the government: French,” criticizes Jean. Something that the rehearsal Strengthen the foundations (Pocket-size), by the eternal Kenyan candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, who cited, for example, the theses that so many African university students are still forced to write and debate, in their countries, in the language of the old oppressor.

“In Uruguay until recently it was said that indigenous culture no longer existed: that was the official message. They teach it to us at school,” he lamented at the Nat Cardozo meeting in Bologna, author of Origin (Red Fox Books), a tribute in words and drawings to the lesson that twenty indigenous peoples offer on how to live in harmony with nature. “The Western world conceives history as an arrow, directed towards progress. For the Innu, however, it is a cycle. We do not see the human being as the dominator, but rather a part of the system, which depends on the other species. We do not think that the hunter kills a moose because he is very skilled, but because the animal gave its life,” Jean clarifies.

In three decades of activity, the Lee and Low publishing house has developed another teaching. “Our mission is to publish works about and for everyone. Over the years we identified marginalized groups that we added. It is always said that ‘diverse books don’t sell’ and we wanted to disprove it with a profitable company,” said Jason Low, director of the American label. Faced with a dismantled stereotype, the editor shared another authentic one, which still inhabits many bookstores. The one that leads to placing a thriller on the “African American literature” or “LGBTIQ+” shelf instead of “mystery,” just because of the skin or orientation of its author. Which, on the other hand, reduces visibility; therefore, success. And, then, it facilitates the prophecy that these novels “don’t sell.”

With the success of Kukum, Jean has perceived the opposite: a growing interest, especially among those under 35 years of age, more sensitive to causes such as climate change, decolonization or identity battles. Although, at the same time, resistance remains the same, or even increases. In Spain, the same as in Canada. The Innu writer and journalist points out: “The Government adopted a law that prohibits denying the consequences of residential schools, in the same way that you cannot deny the Holocaust. People in Quebec perceive themselves as a good society. When people talk about colonization they say: ‘That happened in the US, not here.’ It’s hard to realize that the story is not exactly what you were told. Our school textbooks start in 1492, but archaeologists have shown that in my community people have lived stably for 5,000 years.” And he maintains that Kukum He is awakening many followers, who send him messages like: “I feel embarrassed. What I can do?”. The author’s first advice is summed up in one word. Innu like him would say “aimitau”. On the island of Johnston, it would be “ᐅᖃᓕᒫᕐᓂᖅ”. “Heluhelu”, in Hawaiian; “chilcatun” in the Mapudungun of the Mapuches. What does it mean? Very simple: read.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#struggle #indigenous #literature #child #hear #story #language