Until now I thought that the unhappiest boat in the world was my brother-in-law's, The black pearl as we called his privateering crew and that, after being shipwrecked on the tricky reef of Chipiona, is slowly decomposing in a shipyard in Galicia awaiting scrapping. In the meantime, the sailboat has lost, due to illness, after the boatswain, another of its crew, Nacho – so brave in the shipwreck and such a great guy -, so the list of casualties is already worthy of the Surprise after facing the Acheron. In comparison, the famous outrigger boat (which is not a Caribbean beat but the outrigger, outrigger or side float) of Luf Island might seem like a happy boat. Not much less.

It is prominently anchored in one of the most spectacular rooms of Berlin's brand new Humboldt Forum, the spectacular amalgamation of baroque palace and modern building (by Frank Stella), built on Unter der Linden avenue halfway between Alexanderplatz and the Brandenburg Gate, on the former grounds of the demolished Palace of the Republic (from the former East Germany), which in turn had occupied the space of the Berlin Schloss, the Berlin Palace converted into ruins during the Second World War. The Humboldt, built between 2012 and 2020 and inaugurated at the end of that year, has housed the formidable ethnographic collections of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin-Dahlem, which have been deployed in their new and spacious home in the midst of the controversy over the decolonization of the museums. The way the new center deals with the issue of colonial predation – for example, by showing a lively virtual debate between conservators, art curators, museographers and activists around the Bennin bronzes – is a good example of the ways that have opened in the exhibition of objects looted by colonial powers and the discussion about their return. Luf's ship sails in the middle of that storm.

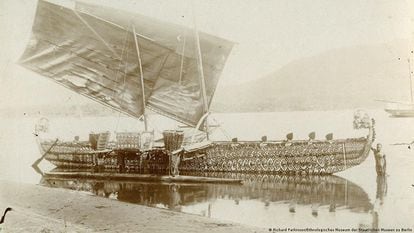

When you see it for the first time, in the area dedicated to sailing in Oceania, your heart skips a beat. The boat, a huge Melanesian canoe more than 15 meters long, weighing 1,358 kilos, two masts with rectangular mat sails and outriggers attached to a large platform, looks like something out of an adventure novel or the cartoons of The Ballad of the Salt Sea (Norma, 2006), by Hugo Pratt, the first Corto Maltese story. You almost hear drums, chants and the rhythmic beating of the oars on the waves as you imagine the ship moving forward, fringed with foam. In fact, next to Luf's boat, and among other vessels, a canoe is exhibited I puked you (tepukei) double-hulled, single-rigged sail from the Solomon Islands, similar to the catamaran on which Rasputin and his Fijian sailors sail when they find Corto adrift. And the world in which Luf's ship was built was very similar to that of Pratt's album, when that area of the Pacific was under German rule and was plied by its cruisers and gunboats (and Lieutenant Slütter's submarine).

The ship, built at the end of the 19th century, comes from Luf, the largest of the 12 Hermit Islands, in the Bismarck Archipelago, currently integrated into the State of Papua New Guinea but then part of the German protectorate of Deutsch-Neuguinea whose main part was the Land of Kaiser Wilhelm.

It makes you want to get on the boat and go in search of La Escondida Island, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, and in the background on the right, past Pitcairn, Easter. Or go for a snack with Friday. Unfortunately for mythomaniacs, unlike the Kon-Tiki —Thor Heyerdahl's legendary raft— in his museum in Oslo, in this case it is not possible to do so since the gunwale is very high. But when you know the history of the boat, you lose the desire to party.

He Luf-Boot, as the Germans call it, is a beautiful ship built without a single nail or any metal (assembled with plant fibers), meticulously decorated with marine and symbolic motifs and heir to a tradition of naval technology that goes back thousands of years. The oily core of the parinarium nut ground over a fire was used to seal joints. The helmet is painted black and white with red drawings of phalluses, turtles, stars and fish lau schematic. Bow and stern are the same. These boats were very valuable possessions, they were kept in sheds that were like large communal houses and many had their own name, although this one, if it had one, is unknown to us, beyond the name. Don Tinan, big boat. With Luf's ship, which had the capacity to carry, with sails or oars, 50 travelers or warriors, we are in the world of the incredibly skilled sailors of the Pacific who, in their boats – with a great variety of types (in the museum you can see six)—discovered and colonized the southern seas by island hopping.

The nautical skills of these people, Melanesians, Micronesians and Polynesians, who did not have instruments, nautical charts or writing and yet sailed through breathtaking expanses of water with the joy and expertise of Kevin Costner in Waterwold, who cannot be denied guts, left Westerners dumbfounded when they arrived in the area (Cook was lucky enough to meet Tupaia, priest-navigator of Raiatea and the only qualified Polynesian sailor interviewed at length by Europeans). For them, the ocean was not a hostile environment but rather their home, as pointed out David Lewis in the classic We the sailors (Melusina, 2012)—never get on a Polynesian canoe without it—where he explains the techniques of these people to orient themselves, including the observation of migratory birds, clouds, wind, waves or phosphorescence (lapa you).

Luf's ship seems to be floating in the room of the Humboldt Forum and it is from the outset, as I said, a lively and stimulating vision when you arrive after visiting the rooms in which the material looted in the German colonies of Africa (and the genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples of present-day Namibia). However, the story of the boat is an amazing drama. Built around 1895, it was the last of its kind and when the inhabitants of the island of Luf wanted to

demolish it, they found that there were too few of them to do so. The population had been decimated—by German punitive expeditions and the diseases brought by the Europeans in their cocktail of civilization and syphilization—to such an extent that there were not enough people to take such a large ship to the sea. Even sadder: the great canoe was supposed to be the funeral ship of a recently deceased chief, Labenan, for his burial in the open sea (I imagine in a Viking style), but since it was impossible to drag the ship to the water, this pious order could not be fulfilled. task.

The boat remained on the beach, a mute witness to the colonial cruelties of the Germans in Luf. In 1882, troops of the Imperial Navy had landed on the island in one of the frequent punitive operations against the local population of the territory, which were usually carried out at the request of commercial firms (such as Hernsheim & Co), which complained of lack of collaboration of the natives in their exploitation plans, which included converting the locals into forced labor and their lands into productive coconut plantations. Accusations of cannibalism (so fashionable) were often used as an excuse to massacre and plunder. In Luf there were 11 days of terror (December 16, 1882 to January 5, 1883). cruiser marines Carola and the gunboat Hyäne (hyena!), they behaved with extreme ferocity, killing numerous people, raping women, burning villages and boats and looting the villages, stripping them of any valuable or interesting objects. Then they let the inhabitants die of hunger. Fifty people out of nearly half a thousand survived. There were no casualties on the German side. in his book Das Prachtboot, Wie Deutsche die Kunstchätze der Südsee raubten (The Magnificent Ship, How the Germans Stole the Art of the South Seas, S. Fischer, 2021), dedicated to the ship as an example of the greedy, criminal and predatory German colonial policy in the Pacific, the historian Götz Aly describes through historical testimonies, including that of his own great-granduncle, a military chaplain in the Kaiser's Army, the desolation caused by the attack.

The abandoned ship was acquired in 1903 from the “dying tribe” by the colonial businessman Max Thiel, of Hernsheim & Co, moved to the island of Matupi (where it was photographed in shallow waters) and sold to the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin, the predecessor of the Ethnological Museum as an exotic ethnographic treasure. Aly questions whether Thiel's acquisition was legal—which would be surprising given the context—and suggests that what he did was take the ship and take it for granted. In any case, there are no documents that prove the sale by the original Lufite owners, among whom would be a certain chief Sini. For Aly, the ship, the masterpiece of the Berlin ethnological collection and the Humboldt Forum, is not only an important testimony of human culture worth preserving, but “an example of colonial tyranny.”

The ship arrived in Berlin in 1904 after being shipped dismantled to Hamburg from Matupi on the steamer Prinze Waldomar. In the capital it was exhibited intermittently and then permanently since 1970. In order to reach its new port in Humboldt, the ship had to sail through the streets of Berlin for two hours and was taken into its room before finishing the new museum. To get it out now, a wall would have to be torn down, which Aly does not consider a problem: “Tearing down walls in Berlin is associated with good memories,” she says. His book was published six months before the museum opened, and his account of how the ship constitutes a testimony to colonial violence and the theft of Oceania's cultural relics, and, as one put it, “a memorial to the horrors of the German colonization”, raised blisters. Even more so because the historian established a connection with the properties stolen by the Nazis and proposed the restitution of the ship. However, the National Museum of Papua New Guinea, in Port Moresby, has declined to request the return of the ship, which it considers is already well established in Berlin as an ambassador of Pacific cultures and a tourist attraction. In 2020, the Berlin museum did repatriate two mummified Maori heads.

Be that as it may, one goes to see a ship and finds a piece of history, an extermination and a floating ciborium controversy. Aly has disgraced those responsible for the Humboldt by not explaining the story well and posing as saviors and guardians of the cultural treasures of the South Seas (the museum has 65,000 objects from the area), as if what had happened to the peoples who suffered the terrible German colonization would have been a natural catastrophe. Come on, the Kaiser tsunami. Looking out on Luf's ship, the wonderful and unfortunate ship that could never sail due to lack of arms, you no longer see only the great adventure of the Pacific sailors, but the heart of darkness, which is everywhere.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#unfortunate #ship #world #South #Seas #Berlin #visit #outrigger #ship #island #Luf