Before I started playing Penrose, I had begun to fear I was losing my capacity to read. When I'd sit down to work each morning, I'd already be drowning in unread text from the day before – 85 open browser tabs, a dozen PDFs, and stacks of half-read books spread across the floor, coffee table, and sofa arms. Some days, all the open tabs and files would crash my laptop as soon as I opened the lid. Other days, my brain would crash before I could even make it through a paragraph, short-circuited by my own greedy desire to learn about anything other than what I was already reading – the history of Roman coins, the speculative links between Moebius Syndrome and schizophrenia, the geological history of Antarctica, a neuroscientist who tried to teach animals to play musical instruments.

Michael Townsend, who developed Penrose through his Toronto-based studio Doublespeak Games, describes it as a 50,000-word “non-linear, interactive novella.” To me that sounded like another brick in the wall of the text-based tomb I had interred myself in, being slowly embalmed by the fruitless fluids of my own curiosity. But I also liked Townsend's work, including A Dark Room, the cryptic survival clicker game that had become an unexpected hit on the App Store in 2013. In the years since, he'd pursued a career of studying minimalist game design, tinkering with unassuming ideas that quietly morph into elaborate arboreal contraptions. He uses games as a medium for thinking more than doing, which can sometimes make his work seem formless and withholding, and other times startlingly immersive and urgent.

Penrose tells the story of a brother and sister searching for clues about their mother, a scientist who disappeared under mysterious circumstances when they were children. In practice, it's less of a narrative than a kind of open-world puzzle game that uses text as a scrollable landscape. It has more in common with memento mori-style games-like Her Story de ella, Return of the Obra Dinn, Myst, or even Metroid Prime-a linguistic peephole into some tragic set of past events that have insisted on spilling over into the present .

The game opens in the third of five chapters, with Peter Penrose, a troubled art student who's agreed to drive Catherine, his sister, into the deserted sprawl of northern Nevada to explore the abandoned laboratory where their mother, Marie, once worked. Peter has no real memories of his mother; he was only a few months old when she was last seen alive. But Cat, who was seven at the time, can't forget her. The disappearance reshaped her life, leaving her anxious and uneasy, everything she'd thought of as fixed and permanent has become eerily tenuous and light as a feather, responsible to be blown away in the next light breeze.

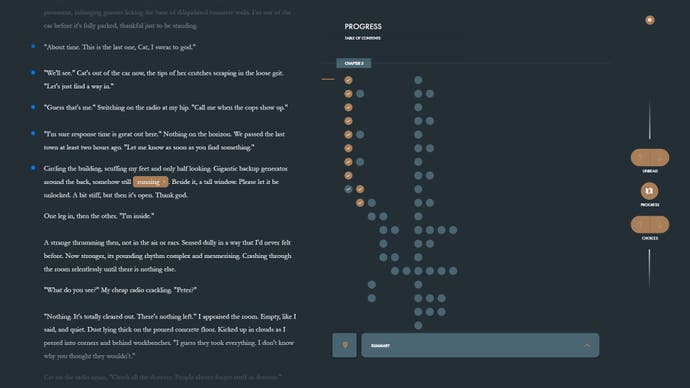

There are only a few paragraphs to read at first, above and below which the text fades into a white blur. It follows Peter's inner monologue as he creeps through the dilapidated lab while Sarah guides him over a walkie talkie from the car. (She's on crutches and can't move well on her own anymore.) When Peter finds his mother's old office in the basement level, he discovers a stack of cryptic notes and a strange machine in an old cardboard box. The word “machine” is highlighted in an undulating orange glow, shooting off animated particles like a newborn star. Tap it (or click on it with the mouse cursor) and the chapter rewrites itself, filling in new text above, below, and in between all the old paragraphs, a small blue bullet point in the margin marking each new addition.

If you read ahead, you'll find out that the police are waiting to arrest Peter on the top floor. Scroll back through a few new paragraphs and you'll find a “running” generator in a room Peter passed but didn't enter. Tap the word and you can change the generator to “seized,” which prevents the alarm from going off. But that introduces a new problem: the elevator he'd taken down to the basement level no longer has power, meaning he never makes his way to the basement to find the machine and Marie's notes. Another quick skim of the text reveals another option buried in the new text: a control system for the alarm that can now be disabled, making it possible to switch the generator back from “seized” to “running,” returning power to the elevator while leaving the alarm disabled.

Soon enough the text starts to open up in galloping leaps. Pressing another highlighted word rewrites the entire chapter from Cat's point-of-view. Later, other characters become the main narrator in chapters you thought you'd already finished, each containing their own small universe of differences. As new chapters are introduced, the timeline jumps from days to decades. The scale is inebriating, feeding a compulsion to see just how many invisible junction points connect one character's reality to another's, something that's beautifully framed by the game's score – from Toronto-based composer Vancorvid – the metronomic pulse of a plucked violin, halfway between a quiz show theme and a countdown timer, notes cautiously climb up through the octave, looking for the daylight of a new thought.

Strangely, the story only becomes more confused as you dig deeper, like twisting a Rubik's Cube to line up the blocks on one side only to push the other sides deeper into disarray. As the game draws back the curtain on both the past – what was going on with Marie in the lab – and the future – what happens after Peter and Cat discover Marie's machine 19 years later – the text becomes eerily abstract. In a funny way, it starts to resemble the earliest text adventures like Zorq and Colossal Cave Adventure, the world reduced to a series of dimly-lit rooms, furnished with cryptically purposeful objects – easels, books, doors, window frames.

Have the characters fallen into a collective hallucination? Have they been inadvertently trapped in a black hole on the far side of the universe? Would they be able to tell the difference between the two? By the end of the game, it can feel as if you've simply run up against the limits of your own cognition, like someone trying to teach a dog about the principles of molecular biology using an elaborate system of treat dispensers and flashing LED light strips.

Roger Penrose, the physicist and recent Nobel Prize winner after whom Penrose was named, believed that mathematics, and not language (or text), was the only real way to understand the laws that govern the universe. Yet, he also famously believed that the human mind could not be understood in terms of mathematics. He has memorably described the mind as a “physical non-computability,” a ghost that haunts the world of numeracy and differential equations with its unknowability, hinting at still another layer of reality that can't be accounted for in even the most radically advanced quantum mechanics.

These gulfs in knowledge can be maddening and inspiring in equal measure, creating their own little black holes that invite us to descend, imagining that we might be able to somehow change the terms of reality if we only knew just exactly how the gears turned. Soon enough three years have passed and you're still sitting on the same couch, at the same laptop, with the same half-read New Yorker story about Thai elephants learning to play the trumpet silently draining your battery by loading and reloading programmatic ads that it will eventually crash your whole system.

Before he became a best-selling author and YouTube celebrity, Penrose developed a series of groundbreaking calculations that demonstrated how it might be possible for an object trapped in the outer perimeter of a black hole to escape before being pulled across the event horizon and lost for good. The maths is beyond me, but the principle as I understand it involves using the momentum built up as the object falls into an ever-shrinking orbit around the black hole, like a marble circling the drain in a sink. To get out of the predicament, the object can simply split itself into two pieces, and use the energy released from shoving a substantial amount of its own mass away to boost its better half onto a new trajectory that will eventually lead it to safety. The trick is learning when to let go. It can take a lifetime to get it right. Sometimes even two.

#Penrose #haunted #interactive #novella #that39s #happy #mess #causality