In January 1324, Marco Polo died in Venice. A merchant who had spent more than 20 years in then unknown lands of the East. And that he left his adventures written in a book that was best-seller when the printing press had not yet been invented in Europe. A myth for travelers and readers. Also those of now: cinema, television series, comics, even video games make use of his figure. Among the dozen films, the stellar 1965 production titled in Spanish stands out. The conquest of an empire; and among the television series, the one that RTVE broadcast for Spain in 1982, with unforgettable music by Ennio Morricone.

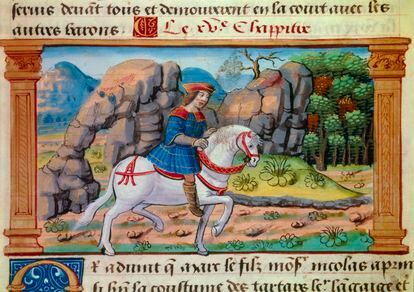

Marco Polo dictated his book to a certain Rustichello of Pisa while both were imprisoned in Genoa. The book was copied by hand and spread like wildfire; More than 140 manuscripts are known. The first printings were made in 1477, in German and Italian. Initially known by its French title, Le dévisement du monde (The Description of the World), soon became better known as The book of wondersor also Il Milione. Although Polo dictated the book from memory – which is always treacherous, exaggerating or inventing – he himself confesses that during his travels he “noted some details on his tablets.”

Who really was Marco Polo? From the first editions of the book he is presented as a Venetian knight or merchant. He must have been born in 1254, but where? The Croatians are convinced that he went to the Dalmatian island of Korcula. The Croatian Government has just restored (or recreated) his supposed birthplace, turning it into a mansion of carved ashlars, Gothic windows and a tower. He merchandising around Marco Polo invades this beautiful fortified island. The surname Polo could be of Croatian origin, yes, but the child Marco would have been taken to Venice by a merchant uncle established there. The island of Korcula was then under the rule of Venice, the great power of the region opposed to Genoa and other marine republics such as Pisa or Amalfi.

Precisely in a naval skirmish between Genoa and Venice, when Polo had already returned from the East, he was captured and taken to Genoa, where he dictated his book. He had accompanied his father Niccolò and his uncle Mateo for the first time when he was only 17 years old. Then he returned alone and gained the trust of the Great Mongolian Khan – the fictional dialogues between Kublai Khan and Marco Polo constitute one of the most brilliant books of the 20th century, The invisible cities, by Italo Calvino. Upon his return, he settled down, married a lady named Donata, had four daughters with her, and upon her death he made a will in their favor. Marco Polo's house in Venice is now occupied by a theater.

Bulletin

The best travel recommendations, every week in your inbox

RECEIVE THEM

To understand and value Marco Polo's feat, we must take into account his time: the 13th century began to leave the dark Middle Ages behind and preluded the Renaissance. Gothic art flooded cathedrals and temples with light, the first universities were established, there was a hunger for new knowledge and discoveries. The East remained a mystery. The few pioneers to enter it had been limited to what we today call the Middle East. Christian pilgrims had reached the Holy Places since the 4th century, among them the Hispanic lady Egeria, around the year 380. Our compatriots were also the Jew Benjamin of Tudela (1130-1173) and the Andalusian Ibn Yubair (1145-1217) who, like Egeria, they left writings about their trips to the East.

Crucial episode in the discovery of the East were the Crusades, begun in the 11th century. But in the century of Marco Polo the crusading dream had died out. And the map of the world changed: in the unknown Far East, Genghis Khan laid the foundations of the Mongol Empire in 1206; Within a few years, that empire stretched from Korea to the Balkans. For the Europeans, paradoxically, it was a great opportunity, since they were allowed to trade throughout that territory, safe from the Muslim power that gripped the south. Cathay (China) and Cipango (Japan) entered the maps.

Marco Polo was one of the merchants, missionaries and adventurers who took advantage of that opportunity. Marco Polo's contemporaries were some Franciscan missionaries such as Juan de Pian del Cárpine, Guillermo de Rubruck, Juan de Montecorvino and Oderico de Podernone, who also left two books of memoirs written. But between 1346 and 1351 the Black Death devastated Europe (200 million dead) and a couple of decades later, in 1368, the Mongol Empire fell, thus ending that era of certain cordiality and exchange between East and West.

He Book of Wonders by Marco Polo is actually the sum of three volumes: First book, Second book and The book of India. In them he describes unheard of things, until then unknown. Like “a liquor such as oil that flows from the earth” (petroleum), “black stones” that burn (coal), paper money (which would not be used in Europe until 1661). He talks about exotic fruits, rice drinks substitutes for wine, gems and precious stones, various silks, spices, fantastic animals – such as the unicorn (actually the rhinoceros) or the Roc or Rush bird that appears in the stories of Sinbad and Arabian Nights―. He mentions “macaroni and other dishes made with pasta”, but it is not true that he brought “Chinese noodles” or spaghetti to Europe: spun pasta was already manufactured in the Arab mills of Sicily many centuries before.

But perhaps the greatest merit of Marco Polo and his book is that, without him knowing it, he does the work of an anthropologist. forward the letter. Describes shocking uses and customs. For example, he says that some burn their dead, others practice cannibalism, they cover themselves with tattoos, they cover their teeth with gold, “they go completely naked, both men and women (…) they have carnal relations like dogs in the street, they do not consider villainy “Let a foreigner dishonor them at will with their wives or daughters.” In Yunan, the husband, after giving birth, goes to bed with the child for 40 days, while the wife takes care of the house. And in India, wives (and sometimes servants) are thrown onto the pyre where the deceased is burned.

Silk and spices are a constant in his book. He does not mention something like a Silk Road (so encouraged now by the Chinese authorities), but he cites the Camino de Santiago as something that was already popular then. As for the spices, we must think that this was the goal of Columbus, who, by the way, kept a copy of Marco Polo's book annotated in the margins in his own handwriting. When on his deathbed his wife and friends begged Marco Polo to confess, in that final moment, whether what he had told in the book was true, he barely stammered: “I have only told half of what I told you.” saw”.

Subscribe here to The Traveler newsletter and find inspiration for your next trips in our accounts Facebook, x and instagram.

#Marco #Polo #man #told