History books, including Wikipedia, date the beginning of the Industrial Revolution to the second half of the 18th century in England and Wales. As a milestone, they put on their altar the steam engine that James Watt devised between 1763 and 1775. But the accumulation of millions of occupation records carried out over two decades by historians from the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom) will force a rewriting manuals and encyclopedia: Already in the 17th century, the English dedicated to agriculture ceased to be the majority in favor of other occupations, such as manufacturing things or in services. Before that machine revolution, a revolutionary change had already occurred in the workforce.

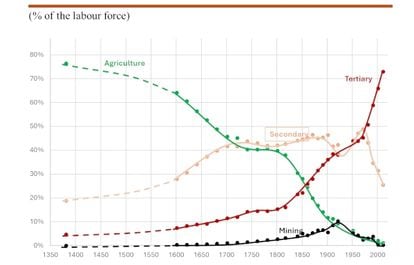

The classic distribution of work establishes a distribution by sectors whose importance has changed over time: the primary, for those related to the countryside and fishing, the secondary, focused on manufacturing, and the tertiary, that of services, which for a long time was called white collar. There were always workers in the three sectors (to which a quaternary dedicated to research and technology should be added). But in England and Wales a complex transition occurred at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, the result of which was that the primary activities, which had been the basic ones of all complex societies for millennia (since the Neolithic Revolution), in favor of manufacturing and trade of manufactured goods. This new revolution, the industrial one, then spread to the European continent in the following century and, from here, to the rest of the world. Faced with this story, dozens of historians, supported by the analysis of massive data, have dedicated the last 20 years to accumulating evidence to rewrite history.

“By cataloging and mapping centuries of employment data, we see a need to rewrite the story we have told ourselves about Britain's history,” says Leigh Shaw-Taylor, professor of economic history at Cambridge. “We have discovered a shift towards employment in the manufacturing of goods that suggests that industrialization was already taking place more than a century before the Industrial Revolution,” adds the project leader. Economy Past, on whose website you can spend hours viewing the evolution, chronology, geographical distribution and demographics of the revolution. The page, its maps and statistics are nourished by 160 million documents from between the beginning of the 14th century and until 1911. Among them, there are parish and municipal archives, censuses, testamentary archives, death records… of several million people in those who specify what they did.

Research shows that already in the 17th century the workforce performing agricultural tasks experienced a sharp decline, while the number of people manufacturing goods increased: from traditional local artisans, such as blacksmiths, shoemakers and wheelwrights, to the explosion of weaving networks. premises that produced fabrics for wholesale sale. Specifically, while the rest of Europe, including powerful France and the German kingdoms and territories, continued to rely on subsistence farming, the number of male agricultural workers in Britain fell by more than a third (64% to 42%). between 1600 and 1740. For comparison, 200 years later, in the 1930s, during the Second Spanish Republic, 47.3% of Spaniards worked in the fields. At the same time, by the end of the 17th century, the proportion of the male labor force involved in the production of goods increased by 50%, representing as much as that dedicated to the fields (from 28% to 42%).

The reality is that changes in the distribution of the labor force began as early as the 15th century, with a proportion of people dedicated to agriculture that continued to decline until in the first half of the 18th century there were more individuals dedicated to manufacturing. than to cultivate the field or take care of the livestock. In fact, at the beginning of the 19th century, when the industrial winds began to spread to the rest of Europe, fueled by the steam engine and mechanization, in England, the figures dedicated to manufacturing had already been stagnant for some time. In an example that history is not as linear as they tell it, many parts of Britain were even “deindustrializing,” the researchers say in a note.

In reality, there were several moments when the revolution seemed to go backwards. By the mid-18th century, around the time Watts was perfecting the Newcomen machine to become the supposed engine of the Industrial Revolution, much of the south and east of England had lost their long-established industries and had even returned to the Agricultural work. For example, Norfolk was probably the most industrialized county of the 17th century, with 63% of adult men in industry in 1700. The figure fell to 39% during the 18th century, while those engaged in agriculture rose from 28% % of the total to more than half. In general, the proportion of men dedicated to manufacturing remained flat throughout the supposed initial and central phase of the Industrial Revolution, to decline sharply from the beginning of the 20th century until now, when only 25% are dedicated to manufacturing things. .

The part of the books that talks about the emergency of the service sector will also have to be changed. For millennia, the third sector workforce was limited to administrative and military personnel and little else. Only in the late phases of the different industrial processes, the white collars of bankers and bankers, salespeople, lawyers, insurance agents, educators and health personnel… began to expand their base until they became, in today's societies, in the majority. In the United Kingdom today, almost 75% of work is related to the service sector, while the percentage dedicated to the primary sector is residual. Already in the 19th century the service sector almost doubled.

Child and female labor

Another of the strengths of this project is that they have been able to segregate and organize the data both by gender and age. Thus, they have observed that female work was central during the first phases of the revolution, but it lost prominence during the 19th century and did not recover it until the time of World War II. In 1851, Easington, in the Durham coalfield, had only 17% of adult women employed. However, in one of the southern industrial centres, the hat-making district of Luton, it reached 78%. “We believe that the participation of adult women in the labor force was between 60% and 80% in 1760, and fell again to 43% in 1851,” Shaw-Taylor details in a note. “It didn't return to those mid-18th century levels until the 1980s,” she adds.

When he wrote those stories of children working in factories, Charles Dickens only reflected the harsh reality. Economies Past allows us to trace the relevance of child labor on the map of England and Wales. In the prosperous textile mills of Bradford in the north of the country, more than 70% of girls aged 13 to 14 were working in 1851. Sixty years later, this figure was still above 60%. Also, up to 40% of the girls in the same area under that age worked on the looms. Only with the introduction of legislation limiting child labor and establishing compulsory education for young children was their role in the Industrial Revolution diminished.

“I don't think our history takes anything away from the Industrial Revolution and the steam engine,” the British historian clarifies in an email. “What we are arguing is not that the Industrial Revolution did not take place between 1750 and 1850. What we are arguing is that the structural change in the workforce that was long assumed to have taken place between 1750 and 1850 in fact ended in 1700. “, Add. For Shaw-Taylor, “this early industrialization paved the way for the technologically intensive Industrial Revolution (the shift to steam-powered machinery) that followed.” In a second part of the project, already underway, they want to determine why this decisive process in history began in England and not elsewhere.

You can follow SUBJECT in Facebook, x and instagramor sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#Industrialization #began #England #century #Industrial #Revolution

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/BRRQWHKHTBFDJJ6EREN2ZD5LLE.png)

Leave a Reply