I never love defining one game with another, and not least a game like Harold Halibut, which wears its influences openly – stop-motion, Wallace and Gromit-style Aardman animations, mixed with maybe a bit of Wes Anderson and in all seriousness, Postman Pat – but which also so clearly deserves to be seen as its own thing.

In this case though it's hard to ignore: the setup for Harold Halibut is very similar to First Contact, arguably the most interesting mission in Starfield (and one itself heavily influenced by a Star Trek: The Next Generation episode called The Neutral Zone), where – spoilers! – you discover a seemingly alien ship lurking in a planet's orbit, emitting strange garbled noises over the radio. You soon discover this is actually a ship from Earth – only one that's taken several hundred years to actually get here, leaving it populated by a load of slightly entitled generational descendants of the original explorers, who's only world is the ship's interior, and only understanding of humanity that they can read about in the selected history books and classes they have on board.

As for Harold Halibut, Harold is a lab assistant-cum-janitor on a similarly stranded spaceship that has instead become an underwater enclave, after arriving at a presumed Goldilocks planet that actually turned out to have uninhabitable land. Having set off in the late '70s and since been totally submerged beneath this new planet's oceans, though, the ship has become a kind of strange, alternate-universe time capsule, filled with fuzzy CRT monitors, intercoms with wobbly sound, and very specific kinds of little England jobs worths. (Much of Harold Halibut, a narrative adventure game about completing largely mundane tasks as a wider, more existential mystery unfolds, feels like a trip to the local Post Office, where you're informed you can't send that letter because you've placed your stamp slightly too close to the label. And that's the wrong kind of envelope.)

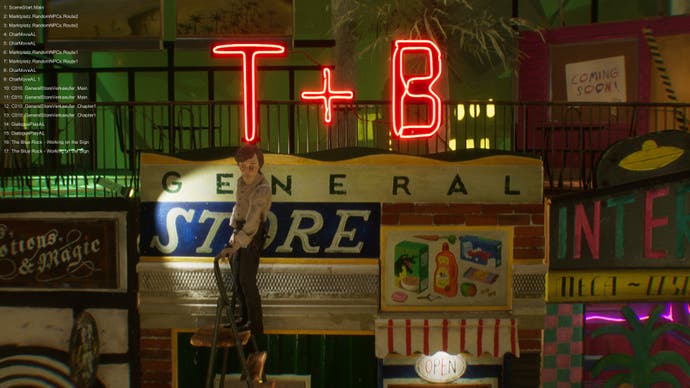

With the animation style in mind it all combines into something exquisitely tactile – there are wonderful buttons and levers and rotating doors – and the environment design, which feels as much like actual set design, proper prop work, is lavish with detail, each room a diorama that's been staged and lit to perfection. It's an eminently screenshottable game, as my bursting storage will tell you, but as much as it's tempting just to linger on the beauty of it – on the little faux chips of paint in Harold's hair, the confoundingly wooden-yet-fluid animation – the real magic is in how this world's been fleshed out beyond its appearance.

Halibut's world is rich and, strangely, for such a sparsely populated commune in the far corner of the universe, bustling with life. It's a testament to the power of writing as much as style, in how its characters each feel uniquely deep and funny and very humanly weird, and how well it captures the vivid small-world syndrome of village life, contained but perfectly preserved underwater here like a closed terrarium. Like Starfield or Star Trek, it's taken an interesting thought experiment and ran with it – but beyond Starfield or Star Trek, it's given that idea time and space to linger, and in doing so allowed a whole ecosystem of life to blossom out. Don't sleep on it.

Manage cookie settings

This piece is part of Wishlisted, a week-long series on Eurogamer covering some of our favorite games from February 2024's Steam Next Fest. You can read all the other pieces from the series at our Wishlisted hub.

#Harold #Halibut #turns #Starfield39s #side #quest #vividly #human #world