On a day of weakness—one of many days of weakness in a life marked by pain, fear and loneliness—Frida Kahlo took the brush, dipped it in ocher watercolor and wrote with thick lines in her diary: “Diego principle. Diego builder. Diego my boy. Diego my boyfriend. Diego painter. Diego my lover. Diego 'my husband'. Diego my friend. Diego my mother. Diego my father. Diego my son. Diego = Me. Diego Universe. Diversity in the Unit”. That passion close to idolatry that the Mexican painter felt for Diego Rivera, the man of her life and her downfall, is today the feeling that fuels a growing fury for Frida Kahlo. A cataract of variations on an iconic artist whose image, at times, detaches itself from what one day was—or seemed—real.

The novel. Claire Berest writes dry. She is 41 years old. She is Parisian. One day she—20 years old, alone, in the United States, without friends, without English—she saw herself in front of a painting of Frida. She still remembers the almost physical impression of how that woman on the canvas was speaking to her. The dialogue did not stop.

Now he publishes the novel in Spain nothing is black (Irradiador Books), an exploration of the passionate story between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in the effervescent Mexico of the 1930s. The first paragraph of it, with more than 80,000 readers in France, reads like this: “You only see him, without even having to look at him.” From there, with a succession of images full of love and violence, the search for the truth emerges in that tortuous relationship.

“Frida and Diego,” Berest tells EL PAÍS, “they cannot live together or apart. They support each other, admire each other and humble each other. They merge and tear apart. They mix everything: desire, painting, politics. They experience their freedom.” Comrade Rivera dreaming of futures from his Olympus as a revered, messianic artist, capable of saying: “I don't believe in God, I believe in Picasso!” And next to her, she: the big-headed hummingbird, with her eyebrows and Indian skirts from Tehuantepec, always in the shadow of Diego Rivera, so cornered that in Mexico she only had one exhibition during her lifetime. Precisely for this reason, Claire Berest reflects, “Frida would have laughed a lot at the current Fridamania; She would have said: 'You're crazy!'

For the French writer, the important thing is that, seventy years after her death, the strength of her painting is still valid. “The pain of the body, of love, of childbirth, of domestic violence, of abortion, of suicide. She is a painter who, with flat areas and bright colors, captured her reality, which continues to be our reality.”

Theater. Matilde Sanquerin saw two Fridas. This is what the painting is called: The two Fridas. One single, the other married. A double self-portrait with their hearts exposed and, in the background, dark clouds in a dreamlike landscape. That painting, and Kahlo's complex duality—two opposing and contradictory souls—triggers the play Love and revolutionwhich is performed at the Reims theater in Florence this January.

The work is a journey through Frida's writings—letters, poems, diary entries and songs, but also the expressive language of Tehuana dresses and flowers in her hair—that orbits around her lebensraum personal: painting, pain, Diego Rivera, poetry, alcohol, Mexico, music, roots, death, doctors, stubbornness and — of course — love and revolution, the two axes of a life short and torrential that two actresses take to the stage. The two Fridas. Their two souls.

Matilde says that Frida Kahlo represents an icon for young girls today. A symbol of self-affirmation and feminist ideals. “However,” she points out, “the role that the general public attributes to her is not true. Frida never spoke about feminism nor did she put being a woman at the center of her artistic and political activity. Today we are bombarded by the face of Frida for a commercial purpose. Hopefully it will help some to decide to discover who she really was.”

Fashion. Dior. There are four letters that do not sound like a revolution. This year the Parisian brand launches a collection. It's called Dior Cruise 2024. Designer Maria Grazia Chiuri says she was inspired by photographs in which Frida challenges conventional gender norms. “From the age of 19, Frida wore a male suit with a vest in a transgression of her femininity that claimed her independence, especially intellectual,” says the designer.

In her collection there are indigenous skirts, pre-Hispanic tunics, many butterflies – a symbol of transformation so present in Frida's paintings -, flowers, parrots, monkeys and a pink dress inspired by a self-portrait of the artist. The Dior brand states that Frida Kahlo “transcended her physicality through her clothes, which became representation, proclamation, protest and affirmation.” The collection can be seen on their website. 3,000 euro bags. Sweaters embroidered with butterflies for 2,300 euros. A wool and cashmere poncho for 1,700 euros. 900 euro t-shirts.

The robot. Daniela Falini records everything. From Todi, a small medieval town located in the Italian region of Umbria, its altruistic website fridakahlo.it It is a seismograph of the Fridian world. Four thousand people visit it every month. Daniela records everything. And she confirms the perception: there is a boom that borders on apotheosis. Exhibitions of his paintings, photographic exhibitions, films, documentaries, plays, musicals, ballets, operas, literary works, illustrated books, music of different genres, murals painted in dozens of countries, clothing and merchandising of all kinds: from mugs to t-shirts, from Barbie dolls to Lego toys, from Swatch watches to floral perfumes. Even with the acronym FRIDA, a robotic arm that uses artificial intelligence to paint has been named: the Framework and Robotics Initiative for Developing Arts. Cruel paradox.

Daniela Falini says that this boom responds to the fact that Frida represents today “a reference for different human groups that still have rights to claim: mestizos (the artist was German-Hungarian on her father's side, Indian-Spanish on her mother's side), the sick, women, people LGTBI+ or the defenders of local traditions against the excessive power of global powers.” For all of them, blending in with the unibrow and mustache is touching a little piece of her rebellion.

The catalog. Luis-Martín Lozano expresses a paradox on three levels. One: interest in Frida has exploded in the last fifty years. Two: publications that deal with her biography, her Blue House, her cooking recipes or her clothing have multiplied. And three: despite the above, Frida's paintings have been less analyzed; almost pasture for oblivion or reduction to the usual ten paintings. The fossilized topic.

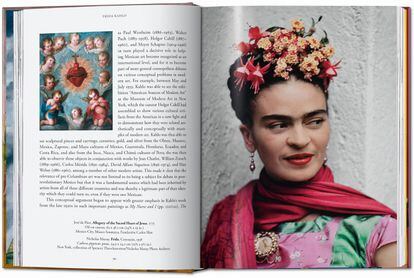

For this reason, Luis-Martín Lozano—who directed the Museum of Modern Art of Mexico and who has thoroughly investigated the work of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo—has endeavored to establish the canon. All works. The 152 autograph paintings of Frida. All of them, reproduced and commented from a new historiographical perspective. The result is the book Frida Kahlo. It is edited by Taschen. It weighs a kilo. It has almost five hundred pages. And from now on it is accessible in a 25 euro version.

In the prologue, the editor highlights a milestone that explains the boom. It was decisive that the North American feminist movement of the seventies made Frida a “bulwark of freedom, of choosing the feminine condition, especially in relation to sexuality, reproduction and the same opportunities for development” between women and men. That made her a global symbol and object of worship. That's where Fridamania began. “Today,” says Luis-Martín Lozano, “his work is inserted in a process very consistent with our 21st century societies, obsessed with individuality, with the consumption of the image, its replacement and immediate disposal, and with the practice of rapacious materialism.”

The origami. And what else? Just these days, up next: the premiere of a new documentary in Utah titled Frida, where filmmaker Carla Gutiérrez travels to the artist's inner world. The graphic novel Long live Frida (The Free Monkey), a book with text by Marie Córdoba illustrated by Juan D'Atri about Frida's construction of Frida. A pop musical in Manchester that addresses her figure. The announcement of a new immersive museum in Touloum (Mexico) that promises a visual and auditory experience. A monologue in Havana titled FK: fantasy about Frida Kahlo, from the Utopia Theater. And an opera in Los Angeles about Frida and Diego's last dreamset on the Day of the Dead and with folk music in the background.

What else? An Al Jazeera podcast about Frida. A tribute to the Mexican painter at the National Gallery of Singapore with her Self-portrait with monkey. And the first book about Frida written with the symbols of augmentative alternative communication for people with disabilities.

Anything else? If he pop-up largest origami in the world with the image of Frida Kahlo. It will be exhibited this January in Milan to beat the world record achieved in Dubai: 8.20 square meters of paper on Frida. An origami montage. With flowers, with butterflies, with a mustache and unibrow. She already wrote it: Diversity in Unity. Frida Variations.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#Fridamania #infinite #pull #eyebrow