Colombians believe in peace processes but less and less in reconciliation. They believe in sitting down to negotiate with the enemy but not so much when it is with the ELN or the Gulf Clan. And they also believe in transitional justice courts but less when they look at each legal case with a magnifying glass. This is shown by the figures from the Americas Barometer, a public opinion survey carried out between the University of Los Andes and Vanderbilt University. which was published this week with the results of 2023. An annual survey with 1,500 respondents in 26 departments that shows, broadly speaking, that for Colombians the theory of peace is still attractive. But it is still very difficult to put it into practice.

When asking Colombians if they like peace negotiations, historically, the majority supports dialogue with armed groups: in 2023, 65% prefer negotiations to end the war. This majority support is maintained even by the Government of Álvaro Uribe, the former president who favored a military solution to the negotiations. This, initially, would be good news for President Gustavo Petro and his total peace policy, which is talking with various guerrillas and criminal gangs throughout the country.

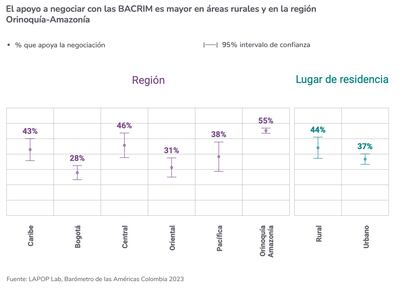

But Colombians believe less in dialogue when they are told who it is with. According to the survey, only 38% of citizens agree with negotiating with criminal groups such as the Gulf Clan. That, obviously, varies by region and how close the respondents are to the war: among Bogota residents, far from that reality, only 28% would support sitting down with criminal gangs. This percentage increases among respondents from the Amazon and Orinoquía, who know the conflict more starkly: 55% would welcome negotiating with these groups. But in general, at the national level, criminal gangs do not have the approval of the citizens.

On the guerrilla side, things are not so positive either. Only 6% believe in a negotiated solution with the ELN guerrilla this year. This guerrilla, it is worth repeating, has made several failed attempts at negotiation with different governments. These failures, and the arrogant attitude that the ELN has had, can explain the pessimism, says Miguel García, co-author of the report and director of the Political Science department at the University of the Andes. “The interesting thing is that public opinion lives in a dilemma: between support for negotiation, but at the same time being realistic versus the possibility of effectiveness,” says García, who has been watching the variations in opinion on peace issues for several years. .

Newsletter

The analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

RECEIVE THE

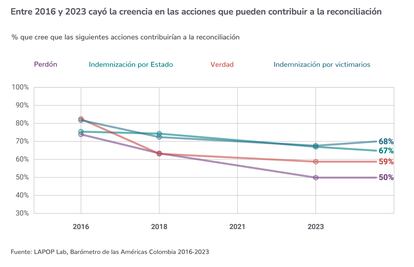

But if negotiating is difficult, reconciliation is also difficult. In 2016, when the peace agreement was signed between the Government and the FARC guerrilla, more than 70% of Colombians believed that reconciliation would be achieved when the perpetrators asked for forgiveness, told the truth about their crimes, and the victims were compensated. Optimism was quite high. The Truth Commission, which completed its major report on the war in 2022, and the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) court, which has held several public hearings on forgiveness and truth, have contributed to these purposes. But despite these efforts, optimism for reconciliation did not increase. On the contrary, it has been decreasing in recent years.

Today only 50% of Colombians believe that forgiveness will lead us to reconciliation, almost 23% less than in 2016. Likewise, the number of people who believe that truth or compensation will lead us to reconciliation is decreasing, year after year. the reconciliation. “There is still hope, but perhaps expectations 6 or 7 years ago were much higher for Colombians,” García explains. “Many see that the JEP macro cases are going slowly, and they may feel that there are unfulfilled expectations. This occurs in a context in which both the right and former peace signatories have been putting pressure on the JEP, so the court is not in a very easy context right now,” he adds.

The JEP, this special court that was born in 2016, has gone through different political crises since it was born. During the government of former Uribista president Iván Duque (2018-2022), who wanted to 'tear up' the agreement, he had to defend himself from the military and right-wing sectors that did not want to see soldiers judged at the same time as former guerrillas. Then Petro came to power and, paradoxically, the most vocal criticisms lately are those of former members of the FARC.

“We are worried that we are going to die owing to the country,” one of them said recently. They criticize the court because the processes are slow, and so are the amnesties. Victims and perpetrators are impatient, and the JEP tries to show that it does have results, that it is committed to reconciliation. This week, for ex

ample, they presented a forest restoration process with the work of former soldiers who committed war crimes.

“These justice processes have their own rhythm,” said the president of the JEP, Roberto Vidal, when asked about the impatience of citizens. “The country is not going to reconcile overnight, that takes time, patience,” added the mayor of Bogotá, who accompanied Vidal on the day the restitution project was launched. Public opinion, unfortunately, has been impatient.

Part of the Americas Barometer report focuses on opinions towards the JEP. Although the court has held public hearings, social media strategies to be more accessible, and symbolic events throughout the country to make itself known, the majority of Colombians still do not fully understand how it works: only 29% say they understand it. That would not be worrying, if you take into account that the majority of Colombians do not fully understand how the congressional commissions or the different courts of the judicial system work. But this ignorance is more worrying if the JEP wants to lead a process of national reconciliation.

“The challenge of the JEP is that they are in the business of administering a different, restorative justice, and perhaps if they begin to show results, the prevention that exists in public opinion will decrease,” says Juan Carlos Rodríguez Raga, professor of political science at the Universidad de los Andes and who analyzed the data from the special court. “But also what the academic literature says is that people, the more they know the courts, the more they support them. And that is what the results show us: when people understand what the JEP does, the more they support it,” he adds.

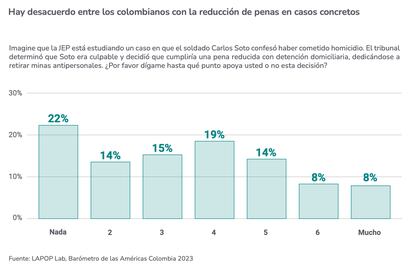

The restorative justice promoted by the JEP, like peace negotiations, is welcomed by a large group of the population, almost 50%. But if the respondents are presented with a hypothetical case, called the former soldier Carlos Soto, the panorama changes. What if it was Soto who committed a homicide in the middle of the war? What if Soto confessed to killing someone and then was given house arrest? What if he doesn't go to jail if he agrees to remove antipersonnel mines? A little more than half of those surveyed do not agree that former soldier Soto has that opportunity.

The government of Juan Manuel Santos said that peace was a difficult pill to swallow. In reality, it is not that difficult to swallow in theory: dialogue, restorative justice, reconciliation with truth and forgiveness, all sound very good to people. It is the day when you have to vote for the plebiscite negotiated in Havana, or the day when you have to judge soldier Soto, or the day when you have to sit in front of a former guerrilla to wait for an apology, that peace is more difficult. . Even so, with their frustrations and slowness, the majority of Colombians continue to respond that it is better to try.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS newsletter about Colombia and here to the channel on WhatsAppand receive all the information keys on current events in the country.

#Colombia #believes #peace #reconciliation #year