The reunion with the French Foreign Legion and the desert began with a Viking ship. I found it by chance at the Mauerpark flea market in Berlin. There, at a second-hand junk stall where they also sold a paper Tiger tank, they had the coveted Playmobil drakar that I had been looking for for a long time. I got it for 20 euros, with all the oars. Life without a Viking ship is not worth it (let alone death: there is no funeral, it is known, like the one held aboard one of those ships). Existential reasons aside, the drakar was good for me to inaugurate the renovation of the Viladrau swimming pool – a small converted pool – and to complete the trousseau of my recently arrived grandson Mateo, who does not know what awaits him. As often happens, small, seemingly inconsequential decisions in our lives trigger a surprising cascade of coincidences. It was arriving home with the Viking ship after an arduous journey taking it as hand luggage on Ryanair and starting to leave Beau Geste all over.

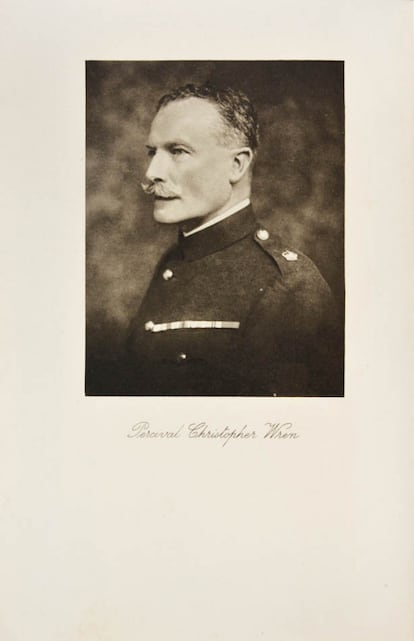

You will remember that in the novel of blood, sand, brotherhood and self-sacrifice by PC Wren, one of the summits of adventure literature and made into a film numerous times, the two oldest of the three Geste brothers, the twins Michael (Miguel in our old editions and known as Beau), and Digby conspire as children to organize whoever dies first “a funeral of viking”, which requires the sacrifice by fire of a ship in which the deceased honorable warrior lies with his weapons, at whose feet the corpse of a dog has been placed. The novel tells how Michael, the firstborn for an hour, and Digby are maneuvering two toy boats in the lily pond of Brandon Abbas, the mansion in which they have been welcomed by their rich aunt, in the company of the rest of their childhood band. , when the little brother, John (Juan), a year younger, is injured and a pellet is extracted from his leg, an ordeal that he endures with exemplary stoicism, which earns him the coveted rank and title (worthy of the Kingdom of Redonda of the missed Javier Marías) of Firme Compañero, Strong Fellow, and a symbolic Viking funeral with one of the small ships and lead figurines. The scene and the twins’ childhood promise will have a terrible adult echo when Beau (I hope I’m not giving anyone a spoiler at this point) dies in the remote fort of Zinderneuf, besieged by the Tuareg after the three Geste brothers have enlisted in the Foreign Legion. French.

Well, the thing is that not only did I find the other day, while my drakar was filling its scratched sail in the pool, an edition of Beau Ideal (my favorite novel and the third of the trilogy he composed with Beau Geste and Beau Sabreur) at the point of book crossing in the Plaza de Viladrau and that shook everything, but another book by PC Wren fell into my hands that I didn’t know existed and that is a prequel or spin off of the original trilogy. The return of the Geste (the edition I found is from 1951 by Lara publishing house) Wren wrote it in 1929 with the not very imaginative title of good Gestures and subtitled Stories of Beau Geste, His Brothers, and Certain of Their Comrades in the French Foreign Legion, and it is exactly that: a medley of stories, in the style of small dioramas of the Legion, focused on the lives of the three brothers and their comrades in the time before the central events of Beau Geste —Michael and Digby’s stay in Zinderneuf, the mutiny, the Arab attack, and the eventual arrival of John in the rescue column commanded by Major Henry de Beaujolais, chief of spahis and old friend of the family (and the Beau Sabreur, good sabreur, from the second title of the trilogy).

The return of the Geste, which has a delicious and very romantic cover – a handsome legionary with a determined look clinging to his rifle – begins with the three brothers in the Legion barracks in Sidi-bel-Abbès reviewing how many nationalities and professions can be found among the members of the unit, from an Austrian count and a former colonel of the Don Cossacks to a fig packer from Smyrna through an Italian opera singer and the employee of a shipping company from Barcelona. C’est la Légion!, where a recruit can respond to an officer who asks him what he did before in life: “I was a general, mon colonel”. Among the stories of legionaries that Wren recounts, many told in Mustafa’s cafe in the barracks, that of one who has been terribly disfigured by the Arabs when he was taken prisoner and in search of whom his girlfriend comes without knowing his condition (the Geste will help him to face the compromising situation); that of the former enlisted Japanese officer who proves himself an ace in martial arts against his bullies; that of La Cigale, a courageous former Belgian cuirassier who is only afraid of loneliness and who encounters the ghost of a Roman legionary with whom he shares experiences, or the very moving one of the two legionnaire friends who die tragically for each other . Stories of the Legion, including episodes that expand or illuminate events of Beau Geste (life in Zinderneuf, the battle of El Rasa, Beaujolais’ march towards the fort with legionaries and mules), and some revelation such as that Digby Geste was as into Isobel as his brother John. To highlight some of the phrases that appear here and there: “In the eyes of a woman in love, any vulgar man seems a hero”, “combat is the best medicine for cafard”, “perfect love ends fear, and perfect fury accomplishes the same.”

The reunion with the Gestes is very much a celebration since the happy circumstance occurs that this year, in October, marks the centenary of the publication in the United Kingdom by the John Murray publishing house of Beau Geste (1924). I am not aware that any event has been scheduled, at the expense of what we fans of Wren’s novel can organize here, among whom are legionnaires so conspicuous, and with such a different profile, like Fernando Savater (who has dedicated unforgettable pages to Beau Geste in its The African adventure) and Arturo Pérez-Reverte (author of the heartfelt prologue to the edition of the novel in the collection of Zenda’s adventure classics). Their thing would be to make a pilgrimage, Lebel rifles on their shoulders, to Zinderneuf, that fort, “isolated in the immense desert as if it were an islet in the middle of the vast ocean”, in whose loopholes the comrades who fall must be placed, to give the enemy the feeling that we are still a considerable force who defend him.

Since in reality Zinderneuf – which the novel places alternately north of Zinder (Niger), marching from Ain-Sefra downwards, and in French Sudan – never existed, the birthday can be celebrated anywhere, in the Sahara or No. And I have done it for now at home, pheasant sentinelle in front of my miniature model of the fort (the Airfix classic) – whose only occupant is the lead figurine of a legionnaire painted by Javier Gómez in his role as The Mercenary -, clinging to my grandfather’s Smith & Wesson revolver and wearing Aleix’s gift of the French kepi with a cotton napkin. I have reread my old edition of the novel (Youth, 1946) humming the legionary march Voila du boudin. He didn’t remember that adjutant Lejaune (“the only man who at first glance seemed bad to me, completely bad,” says John), Sergeant Markoff in the movies, had previously served in the Belgian colonial army in the atrocious Congo of Leopold II, whence he was! they had been thrown out for their cruelties!: sacré chien d’adjudant!. I also didn’t remember that Digby dies in the last pages when a Berber’s explosive bullet hits him in the head while he, John and some friends who have deserted cross the Sahara posing as Senussis on a pilgrimage from Kufra to Timbuktu. Wren must have been in a hurry to finish after so much sand because he settles in three sad paragraphs the death and burial in the dunes of Michael’s poor twin, without a Viking funeral.

Perhaps the anniversary is not the time to debate again whether Wren, whose biography is full of dubious data, served in the Foreign Legion as he claimed. It seems not – as Martin Windrow explains in his splendid book on the legion Our Friends Beneath the Sands (Phoenix, 2010)—and that the details that make his novels so interesting and realistic, including that of the legionnaires placing their dead comrades in the loopholes of the fort besieged by the Tuareg, were provided to him by a former legionnaire in a bar (one can imagine thirsty). Be that as it may, how good it is Beau Geste (and the two novels that followed it), and what a desire to rush to enlist in pursuit of atonement, redemption, pure adventure, or oblivion. Comrades of the walls of Zinderneuf, clinging to your last duty as to your rifle, with your eternal gaze on the infinite shining dunes, wait for us. Soon we will be with you, brothers.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

#Celebration #shots #embrasures #Fort #Zinderneuf #years #Beau #Geste