EL PAÍS offers the América Futura section openly for its daily and global information contribution on sustainable development. If you want to support our journalism, subscribe here.

Luis Martínez, a line fisherman, is not scared by that enormous oil platform stuck in the sea that, like a watchful metal mass, is behind him while he remains in his modest boat. But there are waves of life that worry you. “We left at three in the morning. It's 12 noon, and we only have about seven kilos of fish,” he says. And he shows the catch of him: a few whitecaps (Paralabrax humeralis), and maidens (Hemanthias peruanus). “It's not like before,” he adds, remembering the times when, in just two or three hours, fishermen brought in 30 or even 40 kilos. Even so, from this northern sea, according to the Ministry of the Environment itself, 70% of the fish consumed throughout the country comes from it.

In Cabo Blanco and neighboring areas, for about ten years the National Service of Protected Areas (Sernanp), a Peruvian State agency, has been trying to create, with the support of some NGO, the Grau Tropical Sea National Reserve. As Silvana Baldovino, from the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law, says (SPDA), “it has been a commitment of at least three former presidents and their respective Ministers of the Environment, but the file is not moving forward.”

If created, the protected area would have about 116,000 hectares located in the sea and on the coast. In addition to Cabo Blanco, it would include the Máncora Bank, an extensive marine ecosystem located 40 miles out to sea, where yellowfin tuna live (Thunnus albacares), the conger (Genypterus maculatus), the sharks of the types Mustelus and Triakis, and the swordfish (Xiphias gladius).

It would also include El Ñuro, a fishing cove where sea turtles abound; the reefs of Punta Sal, which are close to the coast and where you can see corals and seahorses; and Foca Island, an island of about 92 hectares where the Peruvian Current, which is cold, and the Equatorial Current, which is rather warm, meet, almost magically.

Only on Seal Island there are 40 species of fish, 31 of birds and 177 of invertebrates (crustaceans, mollusks, echinoderms), according to the Wildlife Guide From this place. When you approach the meeting point of both currents you can see how the colors of the water vary, in the middle of the foam. Meanwhile, dozens of sea lions yawn on the rocks and hundreds of birds hover tamely on the cliffs.

If the reserve is created, the percentage of marine ecosystems that have protection in Peru would increase, which only reaches 7.6%. But, according to Baldovino, “there is a lack of an articulated vision of development, which makes it impossible to identify priorities.” The sea, he adds, is key to food security, it energizes local economies and is a basic foundation of our identity.

On these caressing beaches, fishing is still done on rafts made from wooden logs that move with the help of the wind. Even larger boats carry their sail so that the generous airs help them return. Alberto Jacinto, a veteran fisherman, says that there are still numerous fishermen who leave and return only moved by the sails.

Predation and other evils

But there are also large industrial boats that, as another fisher consulted points out, “as soon as they see the school, they jump in.” Strictly speaking, Peruvian legislation provides that the first five miles from the coast are exclusively for artisanal fishermen, those who capture, at great risk, the species that are enjoyed at the family table or in restaurants.

If the reserve is created, industrial boats, which capture tons of fish, will be able to continue working on the Banco de Máncora, which is far from the coast. They would rely on the Law No. 26834 provides that “acquired rights” be respected, that is, the rights they obtained to fish before the new protected area was created. Even though the same regulation clarifies that these must be exercised “in harmony with the objectives and purposes” of the protected area.

The matter becomes more relevant because, last January, the National Fisheries Society (SNP) – a private trade union organization – filed a lawsuit against the National Service of Protected Natural Areas (Sernanp), so that industrial boats fish in the Paracas National Reservea protected area located to the south with many hydrobiological resources, very emblematic for ecotourism and that would be affected by large-scale fish capture.

Everything indicates that industrial fishing companies are not very supportive of protected areas, as is the hydrocarbon sector. Near Cabo Blanco, at least 30 oil platforms emerge from the water like undisturbed monoliths. Some are in disuse, but others are still active. Part of the new reserve would be superimposed on several extraction lots already awarded. Hence, the Ministry of Energy and Mines (Minem) is the entity that most opposes the new reserve. In a document that América Futura was able to examine, thanks to a source from the Executive, representatives of this ministry go so far as to say that if the protected area is established, this will cause “present and future investments” to be withdrawn. The oil companies, and the lots, have been there for decades, they have “acquired rights.” But his work has not been so clean.

A report from the Mongabay Latam portal, published in November 2019, reported that 88% of the oil spills produced since 2009 (a period in which 1,543,139 liters were spilled) occurred in the northern Peruvian sea. And in 2020 another one happened right in front of Cabo Blanco, at the facilities of the now absent oil company Savia SA.

ghost fishing

A white gar (Caulolatilus prínceps) takes a hook from a fisherman whose boat is stranded near Cabo Blanco. Perhaps to show that, despite everything, this sea is still wasteful. There is, however, another ghost haunting the area where the reserve would be created: the ruthless trawlers that can still be seen in the area today.

Ricardo Bayona, captain of the ship Confianza en el Señor, which has just landed in La Islilla, the cove in front of Seal Island, confirms having seen one that day. He has done better than Martínez: he has caught about 22 kilos of fish, especially whitecaps, in about seven hours. But he no longer finds groupers or conger eels. “The problem is that trawlers enter here,” he says.

SEBASTIAN CASTAÑEDA

Trawling, which in Peru is authorized beyond five miles, throws a net to the seabed that destroys almost everything: small fish, large fish, shellfish. It destroys the marine ecosystem and that is why it is being banned in several countries. In front of Máncora, one night what appears to be a ghostly-looking trawler is sighted.

You can see its enormous sail and two crossed masts, which, according to the artisans, is what characterizes it. Industrial boats use trawling on the Máncora Bank to fish for hake. But there are medium-sized trawlers hanging around near the coast. The Ministry of Production must control them, but at the close of this edition it did not respond to América Futura's questions about its presence in the area.

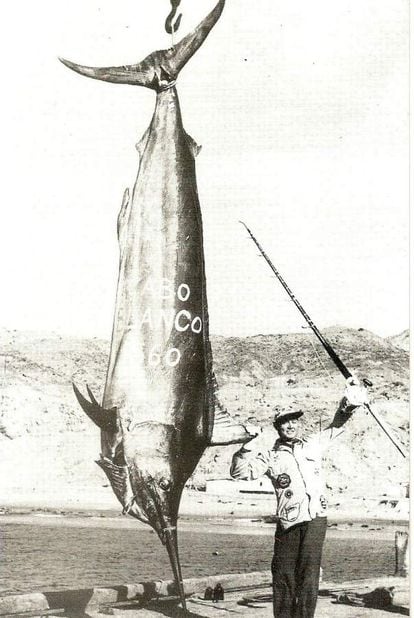

Fishermen agree that the scarcity of large fish is striking. Something that leaves a certain mantle of melancholy because the world fishing record, not surpassed until nowwas obtained in 1953 in Cabo Blanco by the North American Alfred Glassell, who captured a black marlin (Makaira indicates) of more than 700 kilos.

When consulted by this newspaper, Sernanp maintains that the creation of the new reserve is “a priority for the Peruvian State.” He even says that the supreme decree creating it has been pre-published, to open the door to its existence. But resistance to a more sustainable sea remains.

Rosendo Mimbela, an experienced diver who lives in Los Órganos, a cove neighboring El Ñuro, says he harpooned, about 15 years ago, a 140-kilogram small-eyed grouper, which previously weighed more than 300 kilos. Christian Hidalgo, chef and businessman who owns the Tao restaurant, says that “if there is no fish, there is nothing,” aware of the risk for the culinary art.

Yuri Hooker, a biologist who knows Seal Island well, remembers that, by not protecting at least 10% of its marine ecosystems, Peru is failing to comply with the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. In El Ñuro, a ship unloads tons of saw (Scomberomorus saw) and even gives away, without reservation, some copies. There is no way to know if it is the last scene of a present that is running out.

#decade #waiting #law #protect #sea #produces #fish #consumed #Peru

Leave a Reply