The rabbit had arrived at the Vitale house in Montevideo with the worst of fates on its back: ending up stewed in the family pot. But chance intervened and the lucky man ended up in the arms of Ida, the smallest of the offspring. “Who kills a rabbit?” asks the poet Ida Vitale (Montevideo, 1923), sitting in front of the river – almost the sea – of the Las Flores resort, in the south of Uruguay. She says that her friend, her rabbit, nameless and somewhat smelly, accompanied her during a period of her childhood, until her chance, the same one that one day gave it to her, also took it away from her. “In the end he escaped, went somewhere and they ate him.” The aforementioned left the house, but not the memory of its former owner. Later, it would reappear among his verses: “They gave you a rabbit / They let you love it / without having explained / that it is useless to love / what ignores you.”

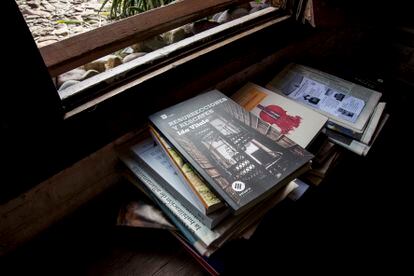

Vitale, who turned 100 years old in November, remembers the ill-fated rabbit when the interview—chat, to be fair—that he gave to EL PAÍS in Las Flores came to an end. The untimely appearance of a black cat stole his attention and he quickly left the room to catch it. “I would have liked a cat or a dog, but it was a rabbit,” he would say later. In his light walk he stopped in amazement at a solitary flower, at the irregular shapes of the clouds and at the low tide. “You have a whole world over there,” he comments. Since December he has been here, almost untraceable in a house overlooking the beach, resting with his daughter Amparo Rama. These years have been busy: he received the Cervantes award and the Guadalajara International Book Fair award in 2018, the Federico García Lorca award in 2016, the Reina Sofía award in 2015, among others. He participated in literary fairs in Europe and America, in tributes and conferences, and recently presented the documentary Ida Vitale.

What follows is a fragment of the interview with this poet, translator, essayist, teacher, which began with the deranged song of the cicadas and ended at dusk with the misfortunes of the ungrateful rabbit. Her refined speech and her indefatigable humor, the reader will see, enjoy impeccable health at her “exaggerated age,” as she often says.

Ask. Have they bothered you a lot about turning 100 years old?

Answer. I haven't been very accessible [ríe]. I feel perfect, just a little hot.

Q. “What happens by chance is not coincidental,” says his poem. The back of the world. How much chance was there in your life?

R. Being born is a chance. I could have fallen into a house of bores, but no one forced me to read anything. Well, at random you have to help him.

Q. You helped him, you were a curious girl.

R. All children are curious. Imagine a world of children who are already bored. If you are not curious about a world that is all new and different… Sometimes you get bored of people, yes. Because in families there is everything. There are those that entertain you and those that bore you.

Q. Boredom is a source of wisdom and inventions, says another of his poems. During this time, boredom seems to have little room, amidst so much noise and stimulation. He does not believe?

R. Well, what for some may be stimulation, for others may be boredom. Even stimulus doesn't work.

Q. What does boredom mean to you?

R. It means work to get out of it. There is no other.

Q. You were the only child in a large family, you grew up surrounded by elders. He got bored?

R. I had many uncles, of all kinds. I had an aunt, Débora, who was the director of a school, which can be a very negative thing, but no. She was a restless woman. I grew up next to her and it wasn't bad.

As a child, Vitale took care of the plants in the family house, which her grandmother Galinda named in Latin as did her aunt Ida, a botanist, who died when she was young. From her he inherited her name, her room and her library. She went to school with her other aunt, Débora, a pioneer teacher. She protected her uncle Pericles, the good one, and detested Rosalino, her superfluous doctor uncle. “That's why I tried to be in good health,” she says, laughing. Later, at the Faculty of Humanities of Montevideo, she studied Literature with the Spaniard José Bergamín, her revered professor. She knew and read with devotion Juan Carlos Onetti, she admired Jorge Luis Borges, she was a friend of the short story writer Felisberto Hernández. He named her dog Macedonio, after Macedonio Fernández, the famous Argentine writer.

In 1949, Vitale published his first collection of poems: The light of this memory. The second, given word, saw the light in 1953 and was praised by Juan Ramón Jiménez, an unavoidable reference. She married the critic Ángel Rama and with him she had two children: Claudio and Amparo. During the Uruguayan dictatorship (1973-1985) she would go into exile in Mexico with the poet Enrique Fierro, her great traveling companion. They returned to Uruguay and left again, this time to the United States, where they lived until 2016. “They are here and there: passing through / nowhere,” reads their poem. Exiles.

Q. Do you remember when you discovered the love of reading?

R. There were books in my house and they read to me. There was a library, which was for children, with novels and stories. It was wonderful. There wasn't much poetry. Then I went to [León] Tolstoy because there was also a library of Russian authors. I was a big prose reader. I find the novel admirable, if it is good.

Q. Prose reader who chose to write poetry.

R. By choice or because I suppose I considered poetry to be easier [ríe]. When you get used to admiring what is good, you realize how difficult prose is.

Q. In Lexicon of affinities, says: “Words are nomadic; “bad poetry makes them sedentary.” If a child asked you what poetry is, what would you say?

R. First I would ask him: don't you know something about that to help me? What is poetry? It's difficult to define.

Q. Some reviews describe her as an “essentialist” poet. Does that definition fit you?

R. I don't know what they mean by that! They repeat it everywhere. I must be the representative. You can write that I abhor him.

His great friend Álvaro Mutis, a Colombian poet, said he is envious of the reader who is about to discover Vitale's works, because a pleasure awaits him that he does not suspect. In addition to those already mentioned, the poet published Each one in his night, in 1960, where you can read: “I only accept this illuminated, true, inconstant world of mine. / I only exalt its eternal labyrinth and its safe light, even if it hides.” Also walking hearer (1972), silica garden (1980), parvo kingdom (1984), Try the impossible (1998), Plants and animals (2003) and Byobu's ABCs (2004).

Q. When they awarded him the Cervantes Prize in 2018, the jury highlighted that his language is both intellectual and popular. How did you take it?

R. I must have thought: popular? [ríe]. But I didn't say anything. I have always thought that Chileans, for example, handle everything that is popular very well. So that it is not clumsy or unpopular, you have to know how to code it. I love what is popular in music.

Q. Music has been a source of happiness for you, it is very present in your life, in your texts.

R. The music, of course. Music was heard at home. There were also guys who listened to tango, all the time. I don't rule out that they guided me at school. I always liked it a lot and tried to be a singer. There was a teacher who lived very close to home, [la soprano] Olga Linne, from a German family, who was wonderful. She taught classes and from time to time gave a concert. And she was flawless. One day I said: “I have to learn from this woman.”

Q. I can do it?

R. I studied four or five years, when I was young. I didn't go to the movies, I didn't buy chocolates, to be able to pay him. It fascinated me. He charged very little and I suspect he charged me less.

Q. But he took the path of writing and did very well.

R. [Ríe] I would have wanted to be a singer, like her.

Q. Well, there is some of that. In the documentary for its 100 years of TV Ciudad (Montevidian public channel) the editor Valerie Miles maintains that you are a rockstar Of letters.

R. ¿Rockstar? How crazy! I don't aspire. Well, it should be translated as “stone star” [ríe y ríe]. Stone, I accept it.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América newsletter and receive all the key information on current events in the region.

#century #Ida #Vitale #wanted #singer

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TRVGLFXGTJGSTEONM3LGSQLGKU.jpg)

Leave a Reply