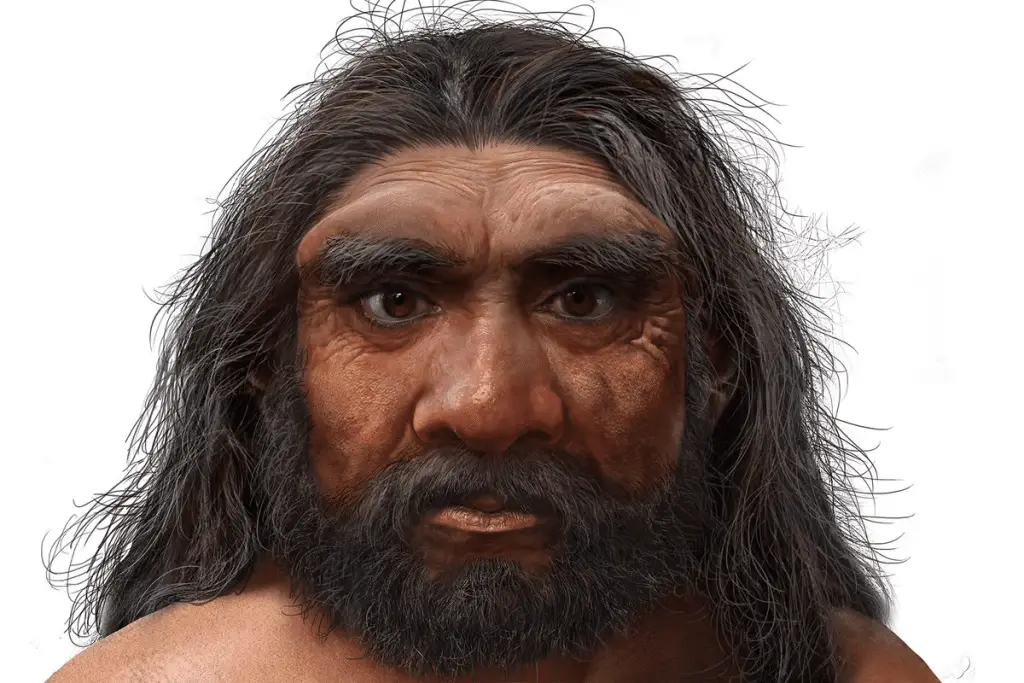

The reasons for disappearance of the Neanderthals which occurred about 30 thousand years ago, only a few millennia after the first appearance of modern humans in Europe, remain controversial and are the focus of research.

The reasons for the extinction of Neanderthals

The last date of appearance of the Neanderthal is commonly cited as approx. 30 thousand years ago (ka). This date follows the emergence of modern man in Europe by several millennia, but our understanding of the exact timing and duration of this interval is obscured by the limitations of our dating methods.

For example, peaks in atmospheric radiocarbon production during this period result in a large degree of uncertainty in relevant radiocarbon dates (Conard & Bolus 2008).

The two species may have coexisted in Europe for up to ten millennia, and perhaps met during this period, although the duration of this coexistence is debated, as is the contact between the two.

The question of what might have happened during these encounters, and what the role of early modern humans might have been in the Neanderthal extinction, has been the subject of intense discussion and a focal point in research.

The disappearance of the Neanderthals is seen by some as a true extinction. Others, however, argue that they did not go extinct, but were instead assimilated into the modern human gene pool.

The fossil record is ambiguous on this point: some modern European human specimens from the Upper Paleolithic have been proposed as potential modern human-Neanderthal hybrids, but this interpretation has been questioned.

Analysis of modern human mitochondrial DNA from Neanderthals and Upper Paleolithic shows no indication of interbreeding (e.g., Ghirotto et al. 2011). However, recent nuclear DNA research has found evidence of limited admixture: a small portion (up to about 4%) of the non-African genomes examined so far may derive from Neanderthals, suggesting that interbreeding likely occurred in the Near East during the first dispersal of modern humans out of Africa, but before their arrival in Europe.

Demographic modeling of admixture combined with territorial expansion, however, indicates that this level of introgression would be produced with very low hybridization rates (<2%) and strong barriers to reproduction between Neanderthals and modern humans, arguing against l 'assimilation.

Pending the completion of the genome and ancient DNA analyzes of the first modern Europeans dating back to the Upper Paleolithic, and following the recent discovery of a third species perhaps coexisting in the Denisova Cave, it is premature to conclude that the level of admixture currently observed constitutes assimilation.

Regardless of this small contribution to the modern human gene pool, Neanderthal populations across Europe suddenly disappeared from the fossil record, and several scenarios have been proposed to explain this observation.

Most invoke as the main factors some degree of competition, direct or indirect, with modern humans or, alternatively, deteriorating environmental conditions.

Competition between different lineages

The hypotheses supporting competition have proposed several possible competitive advantages of modern man. These include technological advances, such as 1) better clothing and shelter, 2) better hunting techniques and more diverse subsistence strategies, which included the consumption of birds and fish, 3) social differences, such as larger group sizes and more social networks developed between modern humans, and 4) demographic factors, possibly including differences in birth and death rates or birth intervals between the two species.

Indeed, important differences have been found between Neanderthals and modern humans in their life history and demography, including faster growth and possibly shorter life expectancy, as well as much higher population density among Neanderthals. Neanderthals and modern humans. Modern Paleolithic humans compared to Neanderthals.

Climate change

The relevance of climate to this debate has until recently been underestimated, as Neanderthals disappeared into oxygen isotope stage 3 (OIS 3) when conditions were thought to be relatively stable. Some recent hypotheses, however, believe that climate instability during the millennia up until the Last Glacial Maximum was a driving force in their extinction.

One model postulates that habitat degradation and fragmentation occurred in Neanderthal territory long before the arrival of modern humans and led to the decimation and future disappearance of populations.

In this view, modern humans would have arrived in areas previously occupied by Neanderthals after the latter were already extinct, and the two species would never have met in Europe.

A similar model views their disappearance as just one of many late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions caused by the loss of an environment with no modern analogues.

Support for a significant climate effect comes from recent detailed paleoclimate records, which suggest that OIS 3 was dominated by climate conditions that were much more unstable than previously thought and may have been precipitated by unusually intense volcanic activity.

Modeling of climate stress (defined as the indirect effects of environmental change) based on these new data detected two stress peaks at ~65 and ~30 ka, the latter appearing to be more prolonged and severe than the former, and possibly related to Neanderthal man. extinction.

This may have been accelerated by the contemporary eruption. However, because Neanderthals had survived previous cold phases, it is difficult to accept climate change as the sole reason for their disappearance.

Furthermore, no association was found between the proposed last appearance dates and major climate events, suggesting they did not go extinct following a catastrophic climate event.

If climate played a significant role, therefore, it would be more complex, perhaps involving environmental deterioration in combination with the advent of modern man, and thus with increased competition for limited resources.

From this perspective, it is the interaction between the effects of climatic and environmental fluctuations and competition with modern humans that would have led to the final extinction of the Neanderthals.

Just like Homo sapiens, Neanderthals organized their living space in a structured way

Because fundamental behavioral differences are often assumed to distinguish Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, the ability to structure space within the sites they occupied in distinct activity areas is often invoked as a key distinguishing trait of our species.

This behavior has never been assessed for both groups at a single site, which hampers direct comparisons to this day. To help resolve this question, archaeologists from the University of Montreal and the University of Genoa evaluated the spatial organization in the Proto-Aurignacian levels (associated with Homo sapiens) and the late Mousterian levels (associated with Neanderthals) at Riparo Bombrini in Liguria, Italy.

By mapping the distribution of stone tools, animal bones, ocher and marine shells on the surface of the Riparo Bombrini site, the researchers were able to produce clear and interpretable models of the site’s spatial patterns, identifying distinct groups of artefacts and materials from to analyze. deduce the behavioral significance of the different groups that lived and worked there.

“This homogeneity in spatial distribution suggests an underlying structure in how these ancient humans used space,” said Amélie Vallerand, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montréal.

“By counting the number of contiguous units of the same cluster type, we could discern patterns that help us identify the activities carried out by these groups.”

“The application of quantitative and statistical methods allowed us to significantly reduce bias and provide compelling evidence that goes beyond qualitative descriptions of spatial organization.”

By combining these spatial analyzes with studies of lithic technology, faunal remains, and marine shells, scientists were able to paint a complete picture of the similarities and behavioral differences between these ancient populations.

Both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens displayed a structured use of space, organizing their living areas into distinct zones of high- and low-intensity activity.

This suggests a shared cognitive capacity for spatial organization.

The main occupancy trends for both groups have been established through thousands of years of reoccupation: the recurring position of the site’s internal hearths and a waste pit that persists on all levels highlights the continuity of the arrangement.

The organization of all three levels was conditioned by land use and mobility strategies: they are structured according to variations in the duration of occupation, in re-occupation intervals, in the number of occupants and in the nature of the activities undertaken. So planning and organization were key.

Neanderthal occupations showed a lower intensity pattern than those of Homo sapiens: artefact densities were of lower deposition and fewer clusters were identified.

There are distinct distribution and space use patterns for each of the levels: Neanderthals used Riparo Bombrini sporadically as part of a high-mobility system in the context of rapid climate change, while Homo sapiens alternated between short- and long-term base camps to adapt to their new territory.

The transition from Neanderthal to Homo sapiens in the Liguria region was characterized by the rapid succession of the technocomplex from the Upper Mousterian to the Protoaurignacian technocomplex (Homo sapiens), without any contact between the two species having been observed.

This study highlights the importance of directly comparing the spatial behavior of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens within the same site, using consistent parameters, to minimize analytical bias.

“There is an underlying logic to how space was used, regardless of what species was present at the time,” the authors said.

“Like Homo sapiens, Neanderthals organized their living space in a structured way, depending on the different tasks that took place there and their needs,” Vallerand said.

#Neanderthals #extinct