It is a rather damning irony that Carl Andre decided to die on the eve of the opening of the exhibition that the Musac de León dedicates to Ana Mendieta, who was the wife of the pioneer of minimalism, accused at the time of having thrown her out of the window from their home on the 34th floor of a Manhattan building in 1985 (and acquitted three years later due to lack of evidence). That day, we interpreted it as if Mendieta, one of those women incapable of the art world separating her work from her murky biography – Frida Kahlo, Dora Carrington or Francesca Woodman are also there -, excessively fetishized as martyrs, had to deal with the shadow of her husband until her last breath. And it is a paradox because the mission of the exhibition, exciting because of the respect it shows for Mendieta as an artist, seems to consist of observing her work and nothing more, without the pathos hagiographic nor the discursive pathos of other recent approaches.

It is not a question of ignoring her tragic fate or of artificially separating the personal and the political—it would be impossible, after all, in the work of a feminist artist of her time—nor of failing to see in her work the poetic reflection of their harsh life circumstances (exile, violence, suicide? Murder?), but the sobriety demonstrated by the exhibition, curated by the late Vincent Honoré along with Rahmouna Boutayeb and Álvaro Rodríguez Fominaya, is commendable. So is the quality of the materials gathered, with the complicity of the heir to this artistic legacy, his niece Raquel Cecilia Mendieta: a hundred works that do not have the exhaustive ambition of a retrospective, but rather aspire to celebrate “the relevance of a contemporary, political and vibrant work”, according to those responsible. It is almost obvious: Mendieta's work has aged better than Andre's, despite the fact that his fame was greater in his time: who do his brick pyramids say anything to today, compared to the ecofeminist vibration that the work gives off? from Mendieta?

During the fall, the Barbican Center in London gave the Cuban artist a leading role in the exhibition Re/Sisters, which traced a genealogy of art that, starting in the sixties, mixed concern for nature and feminist tropisms, as if the fragile destiny of the planet were comparable to that of women. The comparison with her contemporaries worked in her favor: compared to the naive binarism of certain proposals, Mendieta's art contained a tear, as if it were the result of a violence that was not only symbolic.

His work has aged better than Carl Andre's. To whom do the brick pyramids of the pioneer of minimalism say anything today compared to the ecofeminist vibration that Mendieta's work gives off?

When you have perceived that aspect, it is difficult to stop seeing it. It happens with their famous Silhouettes, the central axis of their work, bodies camouflaged in natural environments that seek an impossible communion with the landscape, as if they wanted to return to the maternal womb when they have already been expelled from it and have had to expose themselves, whether they wanted it or not, to misfortunes that were waiting for them out there. Earth, water and fire, the rocks of the road, the moss of the pond and the sand of the desert serve to create living sculptures — “I am sculpture,” she once said, denying a lazy connection to the performance— which are allegories of life, death and transformation. They are influenced by the rituals of Afro-Cuban Santeria, as has been said over and over again, even if it is inappropriate. exoticize to Mendieta or reduce her to the status of someone who spent her life searching for a lost pre-Columbian or pre-industrial paradise.

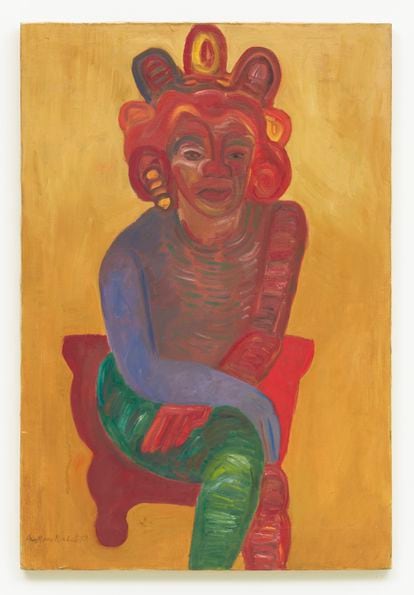

The exhibition is completed with some curiosities: four paintings signed between 1969 and 1971, inscribed in an unexpected neo-Fauvism; images of her anthropomorphic drawings, looking like Neolithic breasts and vulvas, and a set of unpublished photographs discovered in 2022. They provide added value compared to other recent tributes to Mendieta, who has not stopped starring in them for a decade and a half. The only thing missing in this valuable exposition is some counterpoint that exemplifies that his retroactive reconnection with Mother Earth is also, or above all, an aggressive rejection of our arid civilization. For her exile as a child, as part of the call Operation Peter Pan after Castro came to power, when she arrived alone with her sister in the United States (she did not see her mother again until five years later, and her father, imprisoned, until the final stretch of her life). And, without a doubt, because of the situations of racism and violence experienced in that supposedly golden exile.

For example, his series Rape Sceneperhaps impossible to exhibit in the current climate, documented a performance which he made in 1973, when he was still a student at the University of Iowa. After the rape of a young woman on campus, Mendieta invited his classmates to come to his apartment. When they arrived, the door was ajar and the artist was on the floor, bleeding, motionless and mute. She was in the same position as the victim, as documented by the local press. The work, influenced by the Viennese shareholders – especially by the women of the movement, such as Valie Export or Renate Bertlmann – is not present in the exhibition. Yes, however, there are late works that hint, more kindly, at similar aspects. All of them are set in residential suburbs, which translate a duller but equally structural violence: that of having to conform to the dogmas of a society that, in reality, disgusted him. Her communion with nature and her insistent search for her origin (the homeland, her childhood, the womb) were, in all likelihood, more

desperate than placid.

'Ana Mendieta. In search of the origin'. Musac. Lion. Until May 19.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#Ana #Mendieta #returned #home