An apparent game of cat and mouse has been established in Spain in recent weeks, and links the three powers of the State: executive, legislative and judicial. It occurs on account of the future amnesty law: its urgent processing in the Cortes – as a condition imposed by the pro-independence parties to invest the socialist Pedro Sánchez as president – runs parallel to the investigation of judicial cases that, if the law prospers, will be deactivated. And the judges who instruct them have stepped on the accelerator. Last November, when Junts and the PSOE were in full negotiation, studying how to delimit terrorism crimes in the amnesty, Judge Manuel García-Castellón – who had had the case open for four years – issued an order that expressly pointed out that crime to former president fugitive (and leader of Junts) Carles Puigdemont; The PSOE and Junts then agreed on a new wording to try to avoid the accusation, and the judge issued another order that expanded its possible scope. Something similar has happened with another cause linked to processes instructed by Barcelona judge Joaquín Aguirre. With each step that the legislators take, the judges take another in parallel; and vice versa.

In Europe it is difficult to find precedents for this situation; It is also difficult or impossible to find amnesties with characteristics similar to the Spanish one and linked so directly to support for an investiture. But there are some examples of clashes between rulers—or legislators—and judges.

United Kingdom

On May 1 of this year the deadline imposed by the Troubles Legacy Bill (Legacy and Reconciliation of the Problems in Northern Ireland Act), the norm with which all those involved – who have not yet been tried – in crimes committed during the three decades of sectarian violence that devastated Northern Ireland until the signing of the 1998 agreement between Great Britain and Ireland. That day, the judicial cases still alive will be closed (except for those that are very advanced) and from then on, no new ones will be able to be opened due to these events. The law is, basically, a general amnesty—with certain conditionality—for all crimes committed during the 30 years of violence. More than 3,500 people died in that period, in which the British army ended up becoming fully involved in the war that faced the terrorism of the IRA and that of unionist and Protestant paramilitary organizations.

The main political parties of Northern Ireland, their institutions, the British Labor opposition, the Dublin Government and even the US Administration have opposed this amnesty promoted by Rishi Sunak's Government, which, although affecting both parties to the conflict, It is designed almost exclusively to exonerate military veterans who continue to be criminally prosecuted for acts of dirty war on Northern Irish territory.

The Northern Irish judges have conveyed their frustration to the victims regarding the obligation to settle the cases, and in some cases they have accelerated the investigations to try to avoid the “guillotine”—as the deadline imposed by the amnesty law is known—of May 1. . All, however, have assumed the consequences derived from the law.

What affects the most is what happens closest. So you don't miss anything, subscribe.

Subscribe

Six investigations have already entered the procedural phase. Another 13 are almost ready to go to trial. But the pending cases are piling up, and there are not enough coroners (the judge conducting the initial instruction) to move them forward. “We are trying to inform the affected families, who belong to different communities [católicos o protestantes], and that they obtain the truth of what happened to them through a judicial investigation, which is how it should be done. But with a deadline as peremptory as that imposed by law, in some cases it will not be possible,” Jon Boutcher, chief commissioner of the PSNI, the British police in Northern Ireland, acknowledged last Thursday.

Judge David Scoffield, investigating the murder of five people at the hands of British soldiers in Belfast more than 50 years ago, expresses a widespread feeling among the Northern Irish judiciary: “Together with other magistrates, I have decided that I am not going to raise expectations [de los familiares de víctimas] about the progress of their cases, because it may not be possible.” Last September he accepted the relatives' request to speed up the procedure, because the amnesty would no longer apply if the only thing left pending, come May 1, was the sentence. “I am going to do everything I can, in a reasonable and realistic way, to try to conclude this case. But there are no guarantees that he will achieve it,” he emphasizes. “And I have no doubt that other judges with similar cases, who do not see a reasonable prospect of being able to conclude them, will avoid giving them priority. “To be able to dedicate the available resources to more advanced research.”

France

It is difficult to find in the recent history of France a precedent of legislators and rulers fighting with judges over a specific law. There are also no precedents for amnesties granted in exchange for their beneficiaries supporting the investiture of the person granting it.

The French Constitution explicitly recognizes amnesty. There have been, since the founding of the Fifth Republic in 1958, two great political amnesties; and both have been applied, not all at once, but in several stages, each time expanding the criteria to qualify for the measure. The first was the amnesty for crimes committed during the war and the independence of Algeria, and between 1962 and 1968 it progressively benefited people with more serious accusations and sentences, until it reached General Raoul Salan, one of the ringleaders of the coup d'état against the General De Gaulle and head of the terrorist organization against the independence of Algeria, OAS. The second amnesty affected acts of violence in New Caledonia, a French territory in the Pacific, and was adopted in two stages: the Matignon agreements, which put an end to what was feared to be the beginning of civil war in the territory, They contemplated an amnesty but excluded bloody acts. In 1990, Parliament extended the amnesty to include these acts as well.

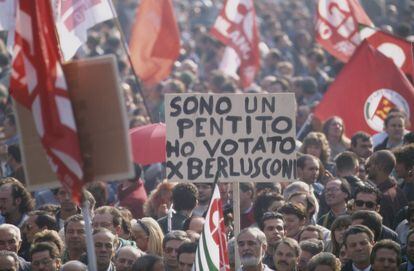

Italy

Italy also does not have a precedent for an amnesty law similar to the one now being debated in Spain. The transalpine country, however, does often experience collisions between the judicial and legislative powers due to new regulations already approved or in parliamentary process. The main difference is that in Italy the majority of the judiciary gravitates towards the progressive orbit and it was during the right-wing governments when the biggest clashes occurred. It happened with the law known as Colpo di spugna on corruption crimes, promulgated by Silvio Berlusconi. The decision was so controversial that the top staff of the Milan prosecutor's office, which had investigated democracy's biggest corruption case—Clean Hands—presented his resignation. The judges refused to apply the rule, which also affected the then Minister of Justice, Alfredo Biondi, and had to be reformed.

Since then, whenever there has been a government led by the right in Italy, these types of collisions have occurred. The latest example is the Cutro decree on immigration, which provides for expanding the cases in which migrants can be detained or their extradition processed. The rule has not been applied by courts such as that of Catania. These days, in fact, the Supreme Court is holding hearings on the State's appeal against the judges of said Sicilian city who did not apply it.

Germany

In Germany, judges are not usually identified with political tendencies. It is very rare, if not unheard of, for political parties to accuse each other of having influence in the judiciary. At any level. The judges of the four federal courts (the Supreme Court, the Social Court, the Administrative Court and the Labor Court) are elected by a committee made up of the 16 Ministers of Justice of the federal states and 16 representatives of the federal Parliament. In the election, consensus is sought and, if discrepancies occur, they do not reach the media. Concepts such as “conservative majority” or “progressive majority” in the courts are not part of the political debate.

Yes, there is some precedent for a controversial amnesty law, but very distant in time and very different from the Spanish case: the so-called Dreher Law, which in 1968 represented a setback for the persecution of Nazi crimes. The text modified the statute of limitations for crimes committed at that time by accomplices of the Nazi machinery (not by the hierarchs who gave the orders) and led to the filing of numerous proceedings against ordinary concentration camp personnel who helped commit thousands of murders.

Portugal

In Portugal, confrontations between legislators and judges have always occurred after the norm was approved in the Assembly of the Republic, not when it was being processed. It has happened with several important laws such as the euthanasia law, which the President of the Republic sent to the Constitutional Court, and the one that should regulate security forces' access to metadata, which has been struck down by the high court. In both cases, the text returned to Parliament, where legal corrections are usually incorporated. In this last legislature, the political pulse has been more between the legislators and the President of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, than between legislators and judges.

The last amnesty granted in Portugal has nothing in common with the Spanish one. It was granted last summer on the occasion of the Pope's visit for World Youth Days and was aimed at those under 30 years of age with minor crimes and infractions. The pardon benefited a thousand inmates: the vast majority saw their sentence reduced and 25% were released.

In the half century of democratic era, Parliament has approved six amnesties (three for religious visits and three political ones). The most controversial one forgave the militants of the terrorist group Fuerzas Populares April 25 (FP-25), who committed attacks in the 1980s in which 17 people died. This amnesty, which had been promoted by the President of the Republic, the socialist Mário Soares, was approved only with the votes of socialists and communists.

Information prepared by Rafa de Miguel, Marc Bassets, Daniel Verdú, Elena G. Sevillano and Tereixa Constenla.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#clash #legislators #judges #conflict #precedents #Europe