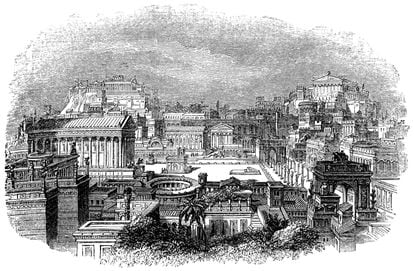

In the 1st century AD, Rome was the first city with a million inhabitants. Until the 19th century, with Beijing and London, no other city reached that population. Although the temporal and human distance that separates us from classical Rome is enormous—it was an extremely violent world, with slaves and emperors—urban problems are repeated throughout the centuries. Juvenal (60-128) already warned in his Satires that the cost of a beautiful residence in a town south of Rome was equivalent to the annual rent “of a slum in the capital.” The French historian Dimitri Tilloi-d'Ambrosi collects this anecdote in his essay 24 hours in Nero's Rome (Criticism, translation by Silvia Furió) in which he describes what distances us, but also what unites us to a world that is ultimately not so far away.

“Some problems are quite similar to today,” explains Tilloi-d'Ambrosi, who teaches courses in Roman history at the Paris-Nanterre University and the Sorbonne and is the author of a doctoral thesis on food and nutrition, in a videoconference conversation. medicine in ancient Rome. “There was enormous pressure due to the lack of accommodation and buildings were being built higher and higher. The insulae —housing blocks— reached five, even six floors, 25 or 30 meters high,” he continues.

Rome, this researcher explains, experienced an intense rural exodus from the 1st century BC, at the end of the Republic: many workers left the countryside to settle in the big city: they were landless peasants, who lived in very poor conditions. hard, working for big landowners. “Many decided to leave for the city and we can see how Rome became increasingly larger, the result of enormous demographic pressure,” he points out. It was a city with flooded neighborhoods, some of which were very undesirable, with homes built in many cases by unscrupulous owners who did not respect the slightest safety standards. What most worried the emperors were the fires, which were devastating, as happened with the fire that devastated the city in the time of Nero, in the year 64 – the emperor was blamed and he in turn, according to a tradition of which Many historians doubt, he blamed the Christians; although the image of the satrap playing the lyre while Rome burned is totally false.

In his book, full of anecdotes and stories, we find many moments that rhyme with the present. Although there was obviously no problem of carbon emissions, regulating traffic in Roman cities was a real nightmare. What today we would call noise pollution was an enormous problem, as pointed out by authors such as Seneca. During the day, there were monumental traffic jams, so since the time of Julius Caesar, the circulation of cars was restricted during the day for the distribution of goods. “Unfortunately, the crash of the iron-clad wheels on the cobblestones of the road inevitably wakes up the neighbors in the middle of the night. “Noise disturbances constitute one of the recurring motifs of satirical or epistolary texts that testify to the experiences in the capital during the imperial era,” writes the researcher.

Throughout the history of Rome, “real anticipated gentrification phenomena” also occurred, writes the historian. Although the use of this term may seem anachronistic, if the definition of the RAE is applied – process of renewal of an urban area, generally popular or deteriorated, which implies the displacement of its original population by another with greater purchasing power – It was exactly what happened on the Aventine. “For centuries, under the Republic, the Aventine was closely associated with the Roman plebs. However, in imperial times the richest social classes settled on this hill and the Aventine then became a neighborhood appreciated by the elites and in which sumptuously decorated luxurious things abounded.”

Like large cities today, Rome was also a very cosmopolitan city, in which numerous nationalities, creeds and languages coexisted. “It was an international city; but so were the ports of Ostia or Lyon,” explains Tilloi-d'Ambrosi. “There were important Jewish communities, people who came from other places on the Italian peninsula, slaves from all over the empire, who formed a very important part of the population. And many oriental merchants. The Syrians, for example, were famous in ancient times for being great merchants, in the wake of the Phoenicians. We see it in Juvenal's texts, although he gives a rather distorted vision, but also in the epigraphy, where many non-Latin names appear. And we also know it from the different cults, to Serapis or Mithras. Religions show the cultural mixtures that occur in Rome and throughout the Empire.”

And, among all religions, the importance of Christians in Rome during Nero's reign remains a mystery. The Annals of Tacitus offer one of the best-known fragments of all Latin literature. Some 60 years after the great fire of Rome, the historian reports that the emperor blamed the followers of this new cult for the fire. “Nero quickly sought a culprit and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a group hated for their abominations, whom the populace called Christians. […] All those who pleaded guilty were first arrested; Then, with the information they gave, an immense crowd was imprisoned, not so much for the crime of having burned the city as for their hatred against humanity. All kinds of mockery joined their executions. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn to pieces by dogs and perished, or were crucified, or condemned to the stake and burned to serve as night lighting, when the day had ended” (translation by Crescente López de Juan for the Alianza edition).

However, for a significant number of historians the chronology d

oes not add up, because, after Nero's persecutions, there were no more attacks against Christians for a century, until Emperor Marcus Aurelius. “They were very much in the minority in Rome in Nero's time,” explains Tilloi-d'Ambrosi. “These are texts that were copied in the Middle Ages and it is possible that some passages were added then. This undoubtedly happened with Josephus and the reference to Jesus in his Jewish Antiquities, which should have been much shorter in the original version. The medieval copyist monks added elements of Christian thought, which Josephus could not have formulated. It is not impossible that the same thing happened with Tacitus because, indeed, this persecution of Christians is very isolated in the chronology. Until the reign of Marcus Aurelius, in the year 177 in Gaul, no major persecutions occurred. And in the 3rd century it is a phenomenon that develops more and more. The persecution of the year 64 tends to be questioned and, in any case, it is a very small community. Christians were more numerous in the East and very minority in the West.” Fake news and alternative truths are not just elements of the present.

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The literary news analyzed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_

#Nero39s #Rome #today39s #world #impossible #rents #gentrification #chaotic #traffic