As we saw last week, complex numbers, in addition to being used to discover buried treasures, constitute, despite their uncertain ontological status, a powerful mathematical tool.

With an approach similar to that of locating buried treasure, numerous geometric theorems can be proven, such as the famous “Napoleon theorem.” The quotation marks indicate that the name should not be understood literally, since it is very doubtful that the author of the theorem was really Napoleon Bonaparte. Coxeter and Greitzer, in their book Geometry Revisited, state that “the possibility that Napoleon knew enough geometry to obtain this result is as questionable as whether he knew enough English to compose the famous palindrome ABLE WAS I ERE I SAW ELBA (I was clever before I saw Elba).” It is more likely that the theorem was proven by his friend Lorenzo Mascheroni, or by one of the other illustrious mathematicians with whom Bonaparte used to associate, such as Laplace, Lagrange or Fourier. And some believe that it could have been demonstrated, a hundred years earlier, by Torricelli or Fermat, who studied very similar geometric constructions. In any case, it has gone down in history as Napoleon’s theorem, and it goes like this:

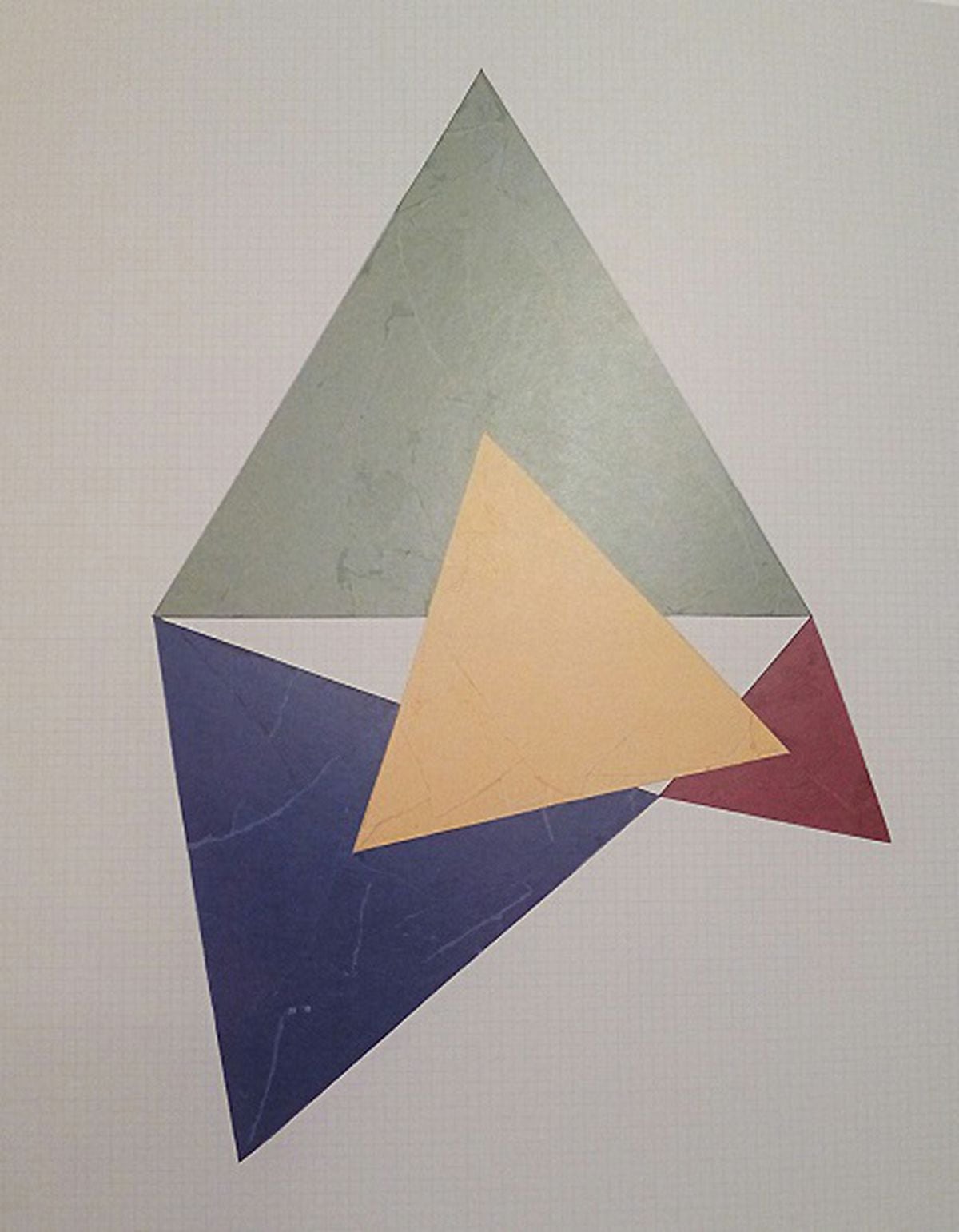

If on the three sides of any triangle we construct two exterior (or interior) equilateral triangles, the centers of said triangles are in turn the vertices of an equilateral triangle (called Napoleon’s triangle).

Placing the problem on the complex plane, as we did with the treasure map, it is easy to prove the theorem; but it can also be attacked with other tools, such as analytical geometry, trigonometry or from certain symmetries. I invite my sagacious readers to try to prove Napoleon’s theorem with their favorite tool.

And after proving it – or taking it for granted – it is not difficult to prove that the center of Napoleon’s triangle coincides with the barycenter of the original triangle (remember that the barycenter, centroid or center of gravity of a triangle is the point of intersection of its medians) .

Napoleon’s problem

We must not confuse Napoleon’s theorem with Napoleon’s problem, proposed by him and solved by Mascheroni, which consists of dividing a circle into four equal parts (or what is the same, finding the vertices of the inscribed square) using only one compass (do you dare to try it?). Mascheroni included it in his book Compass Geometry (1797), in which he showed that any geometric construction that can be done with a ruler and compass can also be done with a compass alone. Incidentally, Mascheroni dedicated his influential book to his friend and protector Napoleon Bonaparte.

There are also some chess problems related to Napoleon, who was a great fan of this game and a more than acceptable chess player. One of the most famous is an artistic finale composed by Alexander Petroff in the 19th century. The author called it “Napoleon’s Retreat,” since it was inspired by the defeat of the French army in the Battle of Moscow in 1812 (if you find the solution, you will understand why).

You can follow SUBJECT in Facebook, x and instagramor sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.

#Napoleons #theorem