Javier Milei’s chainsaw, which had promised to fall on the “caste”, began with the most vulnerable in Argentina: among the first victims of the scrapping promoted by the far-right Government are patients with cancer and other severe pathologies who stopped receiving since the State high-cost medications, essential for their treatments. In the last four months, at least seven people have died while waiting for the medication that kept them alive. The authorities celebrate a cut of 140,000 million pesos (about 150 million dollars) in the health area, but deny the end of the assistance program. Only a few have begun to receive the medication again after prosecuting their cases.

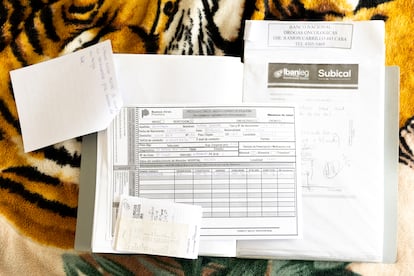

Since December, hundreds of patients have maintained an unequal fight with the State over the medications they normally received through the Directorate of Assistance for Special Situations (Dadse), an organization dependent on the Ministry of Health that grants subsidies for the acquisition of high-quality medicines. , medium and low cost. It is the last resort for low-income patients, including girls and boys, who do not have medical coverage or any type of help.

The head of this organization, Sergio Eloy Díaz, resigned from his position last Wednesday, according to Argentine media. In the previous days, patients had flooded the courts with individual and collective resources and filed criminal complaints against the Minister of Human Capital, Sandra Pettovello, the head of Health, Mario Russo, and even against President Milei for the crimes of “abandonment.” of person.”

“The only answer we receive is that we have to wait, when we know well that these diseases do not wait. The situation is desperate.” The story is from Gabriel Medina, a 29-year-old merchant who was diagnosed, at the end of last year, with a very aggressive cell lymphoma at the level of the clavicle. “Not having any answers causes a lot of uncertainty at a time when the state of mind is essential to cope with the disease. One feels discarded, abandoned while our own life is at stake. “It is not normal that they allow people to die or feel afraid for their lives.”

A vial of Brentuximab, the medication he needs, costs around 10 million pesos (more than 10,000 dollars). Gabriel needs three vials every 28 days. “Clearly, something impossible for an individual to afford,” he says. He has been supporting his treatment, which he had to start urgently, thanks to the solidarity network of organizations and relatives of patients who donate medication that they no longer use. “That is the only thing that gives me hope for life. Thanks to that solidarity, today I can do my treatment on time. But at the same time, I think that I can receive that medication because other patients died. They take you to that point, you have to wait for someone else to die to be able to receive the medication,” says the young man from his house in Monte Grande, in the southern outskirts of the city of Buenos Aires.

be able to breathe

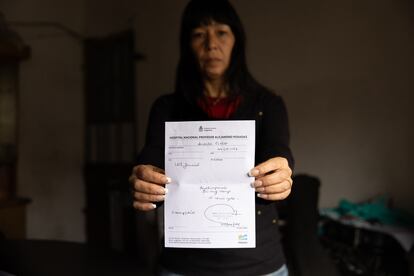

A few kilometers away, in the Buenos Aires town of Quilmes, María Celeste Quintana answers the phone. She does so slightly more relieved: days ago she received part of her medication after five months of waiting in which she had scheduled chemotherapy sessions after, like other patients, having reported her case. In 2019, Celeste, a History and Library Science student at the University of Buenos Aires (UBA), was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer that affects the lymphatic system. Her right lung is affected and, if the disease progresses, it can make it difficult for her to breathe.

The daughter of retired workers, Celeste does not have private or union medical coverage and her health is in the hands of public hospitals in the city of Buenos Aires: there she was treated with repeated cycles of chemotherapy and an autologous stem cell transplant. “But mine is a chronic lymphoma, it will always be there. What I need is a control treatment to prevent it from growing,” describes the 32-year-old woman. Until December, Dadse covered the necessary medication: 28 million pesos every six weeks in Pembrolizumab vials that can only be purchased by the States.

“I was there from November, when I handed in my papers at Dadse, until April complaining because the medicines were not arriving. I was able to have the chemo session, which I had scheduled in January, with a donation of half of the dose that corresponds to me to save the moment,” says Celeste. Not following the established time

s in an oncological treatment is a window that opens for the disease to progress. “We have to fight too much against the disease without having to fight against a State that does not provide medication,” she points out.

Since February, an exhausting judicial tug-of-war began for her: that month she presented an appeal for protection that on March 1 was in her favor. However, the Ministry of Health appealed. “I couldn’t believe it, they appealed saying that my case was not her jurisdiction, that it corresponded to the province of Buenos Aires. Even so, the court ordered that the medication had to be given to me anyway, but they were not doing it, as happens to many other patients,” she reviews.

They received only succinct responses from the authorities. In a television interview, Minister Pettovello justified the lack of medicines by maintaining that purchases during the previous government, headed by Peronist Alberto Fernández, were carried out “in an irregular manner” and that they would move forward in auditing the tenders. For its part, the Ministry of Health, headed by cardiologist Mario Russo, criticized what they considered “press operations” (relatives or the patients themselves who reported their situation in the media) and assured that Dadse “it did not close nor will it close during this administration.”

While patients see their chances of survival threatened day by day, the authorities celebrate a saving of 140,000 million pesos in Health, the result of a radical plan of cuts in a context in which medicines became more expensive by 146% between November and February, 53% above inflation, according to the Center of Argentine Pharmaceutical Professionals (Ceprofar). At the same time, thousands of members canceled their medical coverage after the deregulation of the increases, on which the Government now had to reverse.

“That they say that they stopped the delivery of medicines due to an audit of the program is cruel. In any case, we are not to blame, we are people who need medication to live,” Celeste asserts regarding the organization that during 2023 delivered 22,500 medications and granted 6,170 subsidies.

Mythanasia

“The word is mistanasia: death due to unworthy abandonment of people. A thousand times we had conflict with governments, but never like now was there the will for people to die.” This is how Florencia Braga Menéndez defines it, the project director of the Argentine Patients Alliance (Alapa), one of the six organizations that filed a collective lawsuit to complain about this “unprecedented” situation. “Throughout these years we have never seen anything like this, before there could have been a shortage, some delay, but never something like what we are experiencing today,” adds Débora Bosco, president of the Cancer Solidarity Foundation (Fusoca), which for For more than a decade, he has accompanied patients in their treatments, remedying deficiencies where the State does not reach.

The most distressing thing, both agree, are the patients who “already lost the battle.” According to what they were able to reveal, at least seven patients died in the last four months “while waiting” for their medication, but there may be more. Aldo Javier Pinto, Camila Giménez, Alfredo González, Mariana Floridia, Patricio Romanos, María Teresa Troiano and Alexis Caballero are their names. “My son was a serious patient but they didn’t give him a chance. The medication he needed never arrived. Nothing is going to cure this, but the guilty have to pay because my son had a chance. [posibilidades] of living with medication. He was a young boy, with many projects and a desire to live,” says Claudia, mother of Alexis, a 22-year-old oncology patient, helplessly.

Emails, calls, messages to the authorities’ Instagram accounts, notes on the doors of different organizations: no response to “the hopelessness” of mothers and fathers of children who are going through complex illnesses and who, if they do not restart their treatment, their health condition worsens. “Seeing a child die is heartbreaking, it is very helpless,” says Mirta Hashimoto, the mother of Cielo, 14, who suffers from lupus, an autoimmune disease that attacks and self-destructs vital organs. With proper, lifelong treatment, however, her condition can be stabilized. For that, she needs seven specific medications that today her parents, both without permanent employment since the pandemic, obtain through donations.

“We live every day with anxiety, with the pressure to have your diet (strictly healthy), your medication, your sunscreen from the beginning to the end of the day because lupus affects the skin tissues. Guarantee gas so that you are not cold because of the joints that hurt, when we don’t even have natural gas, we have a bottle. Try to do our best to give them the best quality of life in matters that are sometimes impossible for us. We need a present State, because we all have the right to health and to live with dignity,” says Mirta.

“I never thought that (the authorities) would go to such lengths, to such an inhuman attitude when lives are at stake,” adds Natalia, another of the mothers who fights for her son’s medication, in a long list of chronic, severe and even terminal: “For them, we are a useless expense.”

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América newsletter and receive all the key information on current events in the region

#Javier #Mileis #chainsaw #attacks #ill