Faithful to a ritual that is repeated every year at this time, the golden orioles have returned to eat the figs at home. And this time they have done so with a book under their arm (well, their wing). It is the beautiful The secret of the oriolea collection of 47 poems about birds by Emily Dickinson that has been published by Nórdica in a bilingual version (translated from the English by Abraham Gragera). The volume features full-page illustrations by Ester García that are very evocative of the sublimely intimate, melancholic, spiritual and lyrical world of the great American poet, a clear predecessor in her sensitivity to nature (she had a privileged education for the time in natural sciences and knew a lot about botany and the stars) of authors to whom I am devoted, such as Annie Dillard or Mary Oliver, who escaped to the forest like I do, was a great fan of owls and wrote: “How much hope we placed in those summer days, under the clean, white, hurried clouds, oh yesterday, yesterday!”

Most of the drawings, in grey tones with only a few hints of dull colour, are of birds: one can recognise sparrows, doves, jays, hummingbirds, waxwings, crows, owls and a wren – which at first one would hardly associate with Emily Dickinson. The absence of colour is curious, as the book is dedicated to the golden orioles, whose males have wonderful yellow plumage (hence the link between their name and gold). It is true that the illustrations are thus infected by the sober and transcendent character of Dickinson’s verses, so essential and mayflowerianly Puritan she. One thing that catches my attention is a cardinal, the incandescent red American bird (I will never forget the first one I saw, on the clothesline of a house in Nantuckett), perched on a lit oil lamp, both the bird and the fire seeming to have faded.

I found the drawings of dead birds particularly moving (and pertinent). There is a double page where the sad, lifeless corpses of the little birds are mixed with drawings of insects, which makes me think of the plot of my garden in Viladrau that I have turned into a cemetery for the birds I find dead, some as a result of crashing into the windows despite all the measures I take, including placing, to the amazement of the neighbours, brooms with hats and flags on the windows. I always cover the cold little bodies with moss and bark so that the earth I then place on top will be lighter for these unfortunate creatures snatched from the air. And I never stop thinking of the verses (present in the winged anthology of Nórdica) “Safe in ther alabaster chambers,/ untouched by morning and untouched by noon,/ sleep the meek members of the resurrection,/ rafter of satin, and roof of stone”, which Gragera translates as “Safe in their alabaster chambers, / oblivious to dawn and noon —satin sleeper, stone ceiling—, the gentle members of the resurrection sleep”; and which seem to me to be the continuation or complement of those other works by the poetess, also extraordinary, which appear in Sophie’s Choice (Styron’s novel and Pakula’s film with Meryl Streep) and which become the epitaph of the protagonist and her lover: “Ample make this bed/ make this bed with awe./ In it wait until judgment break/ excellent and fair”. [“Haz amplia esta cama./ Haz esta cama con respeto./ En ella espera hasta que el juicio llegue/ superior y justo”].

The secret of the oriole It is full of Dickinson’s verses that shake and enlighten you: “my sparrow’s fate fills me so much”, “and the dawn was lit with bird wings / and Paradise was that peace!”, “part the lark in two and you will find the music, / one layer after another, wrapped in silver”, “only Gethsemane knows” (in the poem on Charlotte Brontë’s grave, which she calls “dear lost nightingale”), or those that compare the dawn with a fan of topaz. There are of course the verses about the orioles from the poem that gives the book its title and those from The Golden Oriole who magically describe the bird as being touched by King Midas (and turned to gold), and sing of its brilliance and glory.

It should be remembered that Dickinson’s oriole is not ours. The one here and the one that visits my fig tree is the European oriole (Oriolus oriolus) and the one the poetess saw was the Baltimore oriole (Icterus salbula), which are from another family, icteridae (from the Greek ikteros, yellow: it was believed that seeing an oriole cured jaundice), unrelated to the orioles of the Old World but which are very similar, by convergent evolution, in size, diet, behavior and plumage. It is curious to think that when Emily Dickinson saw an oriole and when we see one, they were different birds, although the feelings are the same. Among the orioles of the New World (33 species, including the gonzalito of Venezuela) is the Baltimore oriole, named thus not for the city but for its resemblance to the yellow and black colors of the coat of arms of Lord Baltimore, founder of the colony (later State) of Maryland, on whose flag they are preserved.

The book also includes the most famous verses of the Massachusetts author: “Hope is that thing with feathers/ That sits on the soul,/ That whispers songs without word

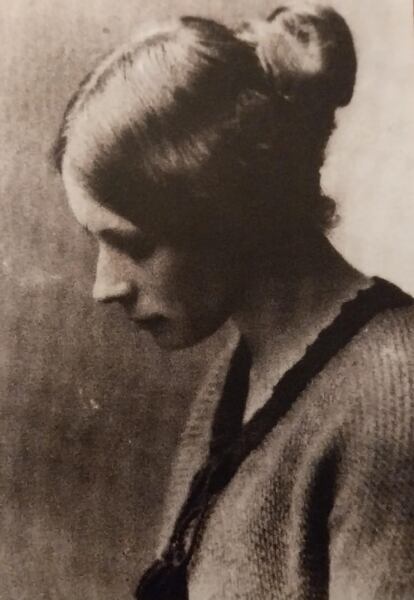

s/ And never, never, stops singing.” The poem is illustrated with a drawing of a young girl in foreshortening (who could be Dickinson herself: her face is not visible) with a little bird perched on her shoulder. The evocative image reminded me of one of the great moments of this summer, along with spending half an hour watching a young fox frolic in the fields of Can Batllic and seeing a bewildered squirrel in my garden (the “crazy squirrel” of Nature (Dickinson’s?) fails in a jump from one tree to another and the aunt falls from ten meters high, barely dazed. That crucial, revealing moment, I was saying, was the discovery in the second-hand bookshop Sweet Books in Girona of an old postcard with the pre-Raphaelite profile portrait of the novelist and poet Flora ThompsonCan one fall in love with a black and white photo of a Victorian author who has been breeding daisies since 1947? You should see the photo. Yeats sees it (as infatuated as I am, but undoubtedly with better literary results) and exchanges Sligo for Candleford.

I have been so taken with Flora—if I may call her by her first name—that, as is often the case with people we fall in love with, I have been quick to try to find out everything about her; which has included launching myself into reading her great work, The Candleford Trilogy (Tin Sheet, 2022, translation by Pablo González-Nuevo), a whopping 636 pages about rural life in Victorian England. As if there wasn’t enough to read in this I returned literary. And I’m liking it, it has something of Thomas Hardy in it, and also of Dickinson, by the way: the omnipresence of the countryside and nature, the essentiality of life.

Flora Thompson, born Flora Timms in 1876 in the Oxfordshire village of Juniper Hill, fictionalised as Lark Rise, tells of her childhood and youth through those of her shadow Laura and her brother Edmund (who would die in World War I like the writer’s own brother Edwin in Ypres) in their small farming village and then in the also fictional Candleford. The existence of the humble people she portrays is hard and precarious by our standards (and by all standards), but they live with dignity and perseverance. “Despite the poverty and the worries and anxiety that accompanied it, they were not unhappy,” writes Flora. “And although they were poor there was nothing sordid about their lives.” They ate things that make Enid Blyton’s teas appetising, told gossip and ghost stories, sang merry tunes (“I wish, I wish it weren’t all for nothing/ And I could be a maiden again for a while”) and looked after the pig who was one of the family, until his time came. It was taboo to wear green, women had a passion for bustles and in every garden there was a rosebush, which did not bear ornate aristocratic roses but humble white ones with a slight pink tint inside and known as “young lady’s blush”. In the little cottage that served as a toilet Laura’s family posted newspaper cuttings (such as the Jack the Ripper stories) and pride of place was occupied by a picture of Gladstone.

I was very interested in what had to do with the natural environment: the beauty of the landscape at the end of summer, when “the ripe, swaying corn in the fields turned the village into an island in the middle of a sea of dark gold” (the same gold as orioles or dandelion wine). The fear that the otherwise wild and rough children felt about stoats. Or the game of sneaking up behind perched birds to try to touch their tails. And I was touched to read that Laura/Flora, who learned to read on her own, loved a worn-out book that a neighbour used to hold up a door and that she gave her when she asked to borrow it: a battered copy of the Travels through Egypt and Nubia by Belzoni, with whom he was able to enjoy “the immense pleasure of exploring the interior of the pyramids in the company of the author.”

Well, here I am in this final stretch of summer, accompanied by my beloved Victorian Flora, surrounded by Dickinson’s birds and with one eye on the sky that lights up again and again, when you least expect it, with the splendor of the beautiful and fleeting orioles, that gift. “What a powerful feeling mine, / to have been invited to this splendid place, / to this party in the great hall of the day!”

All the culture that goes with you awaits you here.

Subscribe

Babelia

The latest literary releases analysed by the best critics in our weekly newsletter

RECEIVE IT

#summer #orioles #writers