EL PAÍS offers the América Futura section openly for its daily and global information contribution on sustainable development. If you want to support our journalism, subscribe here.

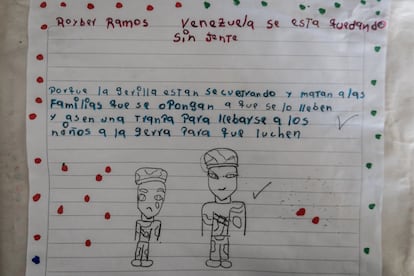

The song Somos Melo, by Donikrap, plays at full volume. The choke sauce floods this small classroom full of children who dance in front of the mirror the steps that teacher Geraldine marks. On the second floor of the school Still I Rise [Y aún así me levanto]located in the heart of southern Bogotá, the teacher Andrés asks the students to respond in English. The little ones wait for the canvases made from egg cartons to dry and, in the Spanish room, a string of self-made newspapers hang from a white ribbon, waiting for teacher Johana to arrive. In one, they announce that “a bacteria is discovered at the bottom of the sea” responsible for the “disappearance of the Titanic”; The judicial section notes how the Government “is doing justice” for the disappeared. And internationally they lament that “Venezuela is running out of people (sic)”: “The guerrilla is kidnapping and killing families who oppose it. “They set (sic) a trap to take the children.”

In no classroom is reality left out. Much less at school Still I Rise, opened five months ago in Ciudad Bolívar, a town in Bogotá where half of the population lives below the poverty line. Not only are the stories of exclusion, forced disappearances or the Venezuelan exodus important here, but it is the reason why the bilingual school was installed there and not elsewhere. In the Lucero neighborhood, which until a few years ago was an invasion, the majority of families live off recycling or “rebusque.” And children are often dragged into the same dynamics of poverty and exclusion. “Not only because they are vulnerable do they have to settle for any education,” says Laura Trujillo, the school’s program director. “They deserve top-quality education and high-level teachers.”

The idea of Still I Rise is precisely that: bringing the International Baccalaureate (IB) to the south of Bogotá. Until now, only students from higher strata who pay at least $600 a month in schools such as Anglo Colombiano, Marymount or Nueva Granada had had access to this educational model. For a few months now, Matilde Loaiza, 13, takes a similar curriculum without paying anything. This education is fully financed—from uniforms to school routes—by an Italian NGO of the same name as the school that receives funds from individuals and companies whose income does not come from illegal mining.

Loaiza still can’t believe she was selected from almost 500 children who wanted to join the school. Trujillo remembers how shy and quiet she was when she was found selling clothes at the flea market, along with her mother and her thirteen siblings. All of them are dedicated to recycling and live in “very precarious” conditions. “Here it shines. Mati It comes from the toughest contexts we know and has had an enormous change,” says the director. “The school and the psychosocial team have that transformative power,” she says. “In Bogotá there is also a level of poverty that one can only imagine in La Guajira or Chocó. These realities exist two hours from our homes.”

Newsletter

The analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

RECEIVE THE

Now Loaiza allows herself to dream of being more than a mother. “When I grow up I want to be a police officer because my sister had a son very soon and she couldn’t be one. She still cries a lot about it,” explains this girl who stopped studying after the pandemic. “We had classes on-line And since we are 14 siblings and there were only two computers and two cell phones… The teachers scolded me a lot for not bringing my homework. That’s why they took me out. I only helped my mother recycle for two years.” Since she signed up, she is putting all her effort into translating everything she thinks or says into English and finishing the book. Good night stories for rebellious girls. “We want to read all the books on the shelf so they bring new ones.”

“We do not want to be volunteers who abandon projects”

The school has been operating with the IB methodology for almost half a year, awaiting official certification. For now, it is a non-formal center for reinforcement and support both for children who already have a school and for those who are out of school. The teachers hope that by next semester they will be able to have the certification from the Ministry of Education as well as the IB to be able to become an approved school. In this first acceleration phase, the school educates 60 minors between 8 and 14 years old; 21 of them are Venezuelans and 11 internally displaced. They hope that they will soon be able to fill the school’s capacity of 180 children.

These were the steps that also followed with the first international school that this Italian NGO opened. In 2018 they decided to open one in Madare, a complex neighborhood in the Kenyan capital that receives an intense flow of migrants from nearby countries in conflict such as Ethiopia, Burundi or Congo. In 2024, upon obtaining certification, they became the first school in the world to offer IB for free. The one in Bogotá would be the second. “We seek to develop in the child a very holistic way of being that at the same time is very demanding with self-regulation, research…” explains Trujillo.

“A police officer earns more than a teacher”

Yamileth Julio Berrío feels that when she drops her daughter Melani, 10, at school, a small part of her continues learning. It has been almost three decades since the last day of school marred happy memories of him in the hallways of his school in the interior of Sucre, in the Colombian Caribbean. “The paramilitaries even said that if they came back and there was someone, they wouldn’t even leave the dogs alive,” she recalls moved. The next thing she remembers is that they ran away—her parents to Venezuela and she and her younger siblings to the capital—and that even the pot of milk was left on the stove because of the rush. “It makes me very proud to know that my daughter is not going to die without knowing how to read or write like my parents,” says this cook and single mother of three girls. “She wants to be so many things when she grows up… Before she made me laugh, but now I think she can. School has been a blessing, I hope they never leave. I wish they would give us parents a class too.”

Trujillo knows that they fill a gap that the State does not occupy. However, she is critical of the role of NGOs. “We don’t want to be like those volunteers who go to complex areas, take photos with the children and abandon the projects. We realized that schools give them a routine and stability that, in times of crisis, become the meaning of their lives. “We came to stay.”

For Víctor Manuel Gómez, professor of Sociology of Education at the National University, the role of certain foundations or NGOs is fundamental in countries as unequal as Colombia. “The State is present but it is present in a bad way,” he says over the phone. “Current teachers are not the most competent people to turn children into active, curious and complete citizens.” That is why, according to the academic, the “vicious circle of poverty” is not closed: “Education is fundamental for social mobility. And projects like this, bilingual and comprehensive, help children’s cultural capital develop.” For the State to be present, according to Gómez, it is necessary to put the magnifying glass on teachers: “We have to greatly reinforce the training, demands and salaries of teachers. In this country, a soldier or a police officer earns more than a teacher.” Their salary ranges between $670 and $1,300.

With pristine black loafers and in front of the word Bravery [valentía] written on the patio wall, he waits for his turn to come at the gymkhana. Erick Manuel Colina laughs out loud and mixes with his team as if he doesn’t care about the story he carries on his shoulders. This 12-year-old Venezuelan has been migrating from one place to another all his life. Abandoned by his mother at birth and with several brothers murdered and in prison, he has traveled from city to city with his grandmother, dedicated to recycling. “I want to learn to read and write quickly,” he says with his eyes on the patio. “It’s fun here. I hope we don’t have to go out again.” In this little oasis, children just seem to be children. Something huge in a community like this.

#elite #school #vulnerable #migrant #children #Colombia