Even the most powerful men in the world need a checking account to rely on. And that of Charles V (for other I, choose yourselves) was linked to a surname: the German Fugger family. Or Fúcar, as we would say around these parts. “They played a crucial role in his election as emperor,” Professor in Economic History Guido Alfani explains to ABC. This is confirmed in ‘Like gods among men. A history of the rich in the West’ (Attic of Books), a conscientious essay in which he examines how the image and role of great fortunes in Europe has evolved from the Middle Ages to the present.

The stories are told by hundreds in its pages, but this family’s story shines with its own light. According to Alfani, the Fúcars arrived in Augsburg in 1367. At first they were workers in the textile and goldsmithing sectors. However, little by little they expanded their sights and, already in the 15th century, “they entered into the lucrative international business of transferring to the papal court in Rome the sums collected from the obtaining of ecclesiastical benefits and the sale of indulgences.” They obtained their greatest level of wealth from the hand of Jacobo el Rico, an exceptional businessman who stood out in the mining sector and in the trade of spices and merchandise.

Jacobo Fúcar was one of the magnates who promoted Carlos’s rise to the imperial seat ahead of Francis I of France. To be more specific, he gave 544,000 florins to His Majesty, which he eventually recovered with interest. However, he also proved to be a visionary in terms of charity, since, with the help of the Fuggerei foundation, he promoted the creation of what is considered the first European social housing project. His nephew Anton became even more linked to the emperor by giving him money to finance his wars against Protestantism. Although he suffered severe losses in the second half of the 16th century when his debtors – including the monarchy – stopped paying him due to various financial problems.

–It states that it was in the 12th century when commoners began to get rich, which marked a radical change in trend

Yes, it was in the 12th century, during the Middle Ageswhen greater opportunities for personal enrichment arose than there had been until then. It was a time when routes were opened in the Mediterranean, in the Baltic, in the North Sea… Thus, merchant dynasties were born that became rich, but also financial dynasties destined to provide services for long-distance trade. Of course, a new rich class was born and, with it, a tendency towards greater inequality.

–Why were they seen as sinners, while the nobles were not?

Theologians of the Middle Ages understood that the rich who were not nobles should use their income to help the poor. They considered that if they did not do so, they were not true Christians. They saw them as sinners and understood that their crime was greed. The aristocracy, according to medieval theology, had access to wealth by divine design; It was part of a social contract according to which, in return, its members were obliged to protect their subjects. On the other hand, nothing was required of a merchant when he became rich. That was the problem: their wealth was not embedded in a social contract that returned to the people in one way or another.

–Where did that hatred originate?

More than hatred we must talk about suspicion. Especially from a specific type of wealth: that derived from finances. For medieval theology it was a sin to make money from money. You couldn’t lend with interest, because time was charged and, since time belonged to God, you were robbing God.

–This idea changed in the 15th century…

The problem is that theologians tried to put an end to this process, but they couldn’t do it. Governments were interested in privately lending money to the State, for example. And they also benefited from these wealthy merchants bringing wealth to the city. In the 15th century, the situation reached such a point that it was absurd to consider them sinners. Therefore, they tried to find new roles for themselves. The first was that they were willing to help the community and the government in times of crisis. When there was a war, a epidemic…An example would be buying grain abroad during a famine. The rich had to help the community, but if they didn’t, they could be forced. It wasn’t something spontaneous. If local governments wanted, they could demand a kind of forced loans.

-

Editorial

Book Attic

–What was the second role?

The second role was magnificence, a concept that already existed in the classical era, in the Roman and Greek worlds. It meant doing great things. If, for example, a family built a palace in the city, it was an aesthetic benefit; Travelers considered her better because they understood that she was rich and prosperous. It was also feasible for them to invest in libraries, hospitals… That was a conversion of private wealth into public wealth. But it did not consist of making donations (munificence); It was not something free. As Plato said in ‘The Republic’, magnificence was a virtue of the philosopher king; the virtue of a ruler. To make magnificence meant to claim a political role, a social obligation.

–Could you give an example?

The clearest example would be Medici family in the XV. When they began to do great things for Florence was when they began to be, de facto, the hidden rulers of the city.

–He also talks about the Fúcars, the family that propelled Charles V to power.

Yes. In the 16th century the imperial charge was elective, and electors were inclined to receive donations. Today it would be corruption. The Fúcars played a crucial role in the election of Charles V. They were the great financiers of the Empire until the moment when the bankruptcy of the state compromised their position. They are a very interesting case; the early example of a family that used part of its own wealth to establish charitable institutions. They were the promoters of social housing at a global level and of the idea that there were poor people who deserved help, but others who did not because they did not want to work.

–Are the poor today richer than those of the Middle Ages?

Access to economic resources between a mid-level nobleman and a poor person from the Middle Ages, and the same couple, but from the Modern Age, is not very different. It is true that today’s poor have more purchasing power than those of the 13th century. The difference is with the current super rich. Theirs is something that has never happened: some have the wealth of a small state. And this is not something we found in the past.

–You ask yourself a question in the book that I would like you to answer for us. What are the rich for? Or better yet, must they be useful for something?

This is the big problem: are Western societies willing to accept that a very small part of the population is very rich without doing anything in return? The expectation that the rich should help society, something that was established in the Middle Ages and endured afterward, is revived every time there is a major crisis. After COVID, for example, the world wondered why they didn’t collaborate more. We could say that the social contract that was created to integrate them into society has been broken, the one through which they stopped being sinners. I think that if they abandon this idea, they would have to take on another role. There cannot be a group that is not connected to the community without an almost explicit contract. Or, at least, accepted by everyone.

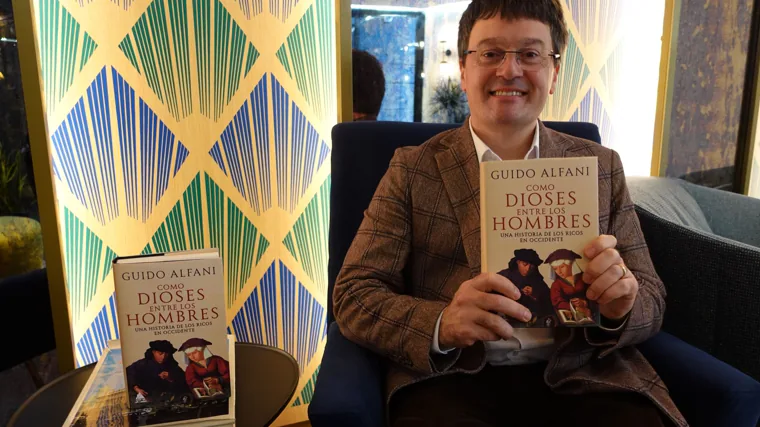

The author, after the interview

–To what extent can wealth influence an electoral race?

Look at the case of the United States with Trump! In addition, he has had the support of another great fortune: Elon Musk. And that, not to mention Berlusconi in my country or Macron in France. The latter is a very good friend of Arnaultwho alternates the position of richest in the world with Musk. In the end, in the West there is a problem with the role played by these super-rich.

–Do you consider yourself a capitalist?

The capitalist system is the best we have found to date. There is only one small problem that Branko Milanovic already explained in ‘Capitalism, nothing more’: he has given us the best when he had a competitor. When faced with socialist countries, or those that defined themselves as real socialism at least, he had his reason to hide his dark side. But today no efforts are made to contain these self-destructive tendencies. Winston Churchill said that we have to get rid of the idle rich, and that we have to do it to protect the system. What do we do today to protect capitalism from its own dark side? Very little.

#Charles #secret #emperor #surpass #Francis #France