After receiving the call from 112, biologist Jesús Tomás quickly went to “fish for little gray turtles” among the houses of Almazora (Castellón). Dozens of newborn loggerhead turtles flooded the road and the coastal chalets, attracted by the light after emerging from a nest on the beach. With its 4 centimeters of shell and 20 grams of weight (less than a strawberry weighs), its survival prospects were not good. The statistics say that only one in a thousand becomes an adult. But that changed the day they were collected: 22 of them entered the LIFE Intemares hatchling program, coordinated by the Biodiversity Foundation of the Ministry for the Ecological Transition. When last Friday, after a year of carethey returned them to their beach of origin, their shell measured 25 centimeters and they weighed 2 kilos: this is the size that in the wild it would have taken four years in reaching. It won’t be so easy to swallow them.

Adapted to places such as the Gulf of Mexico, Cape Verde or the eastern Mediterranean, until two decades ago the Spanish coast was too cold for the loggerhead sea turtle (‘Caretta caretta’). They didn’t nest here. But global warming has changed the situation. The temperature of the sand during incubation determines the sex of each specimen and today its traditional breeding places. produce too many females of this species classified as “vulnerable” at an international level.

«In recent decades, 90% females have been generated. This deviation in the medium and long term is not sustainable,” says José Luis Crespo, veterinarian in the conservation area of the Oceanogràfic Foundation, which participates in the project. But in Spain that doesn’t happen. Levante, being cooler in comparison, has become a ‘producer’ of males for the species. «We are producing 70% males. “It is the only area in the world where this is happening,” he says.

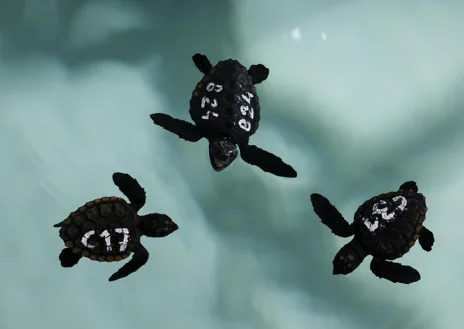

Above, the 22 loggerhead turtles about to be released on the beach of Almazora (Castellón). Below, loggerhead turtles barely weeks old. Some are observed by journalists in the ‘Ark of the Sea’

Is “evolution in action”defines Tomás. Especially because this species normally returns to its birth beach to lay its eggs and is now breaking with this behavior, explains the professor at the University of Valencia and coordinator of the sea turtle nesting protocol that is activated by calling 112. Only the year In the past there were 29 nests spread along the Spanish coast, while in 2024 there were 13. Each one can house 60 to 130 eggs, of which 75% usually hatch. Protocol dictates that most stay on the beach. “They are allowed to go out to sea to respect natural processes,” says Tomás. But there are 20-25% of the eggs, plus 6 or 7 specimens hatched on the beach that end up in the Oceanogràfic facilities.

It’s in the eight ‘Ark of the Sea’ tanks where part of the captive breeding program is developed. Last year, 80 neonates arrived from the Valencian Community, Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Murcia, which have achieved in one year (or less) the size that they would normally reach in four.

Training

“For a human, if I give him more food and make him warmer, he doesn’t get taller, but reptiles do have that plasticity,” says Crespo. The recipe for success is to keep the water clean, at 24-25 degrees, give them veterinary care and a good daily diet that starts at 4% of their weight and ends at 10%. The first menus are a floating porridge of fish and cephalopods, and then it evolves into pieces of their future prey. «If they have all these needs covered, animals grow exponentially», explains the veterinarian.

Before returning to the sea, the turtles are trained in a 600,000 liter outdoor lake so that they «muscle», they are made to live with birds and invertebrates so that they «socialize» and they are offered live prey, such as jellyfish, so that they learn to feed themselves. Only then will they be ready. “The sea is very hard,” warns Crespo.

Loggerhead turtle in the bodybuilding tank, one year old

They don’t have data yet on how much all this training improves the survival rate, but they’re working on it. The Cisneros and Quiteria turtles released in Almazora carry a geolocator, and they are not the only ones. In recent years there have been marked 50 copies with one year. The idea is to unravel not only whether they survive, but what they do during the “lost years,” the early stages of life when it is not clear where they go or what they do.

This marking “tells us things that we didn’t know before,” acknowledges Eduardo Belda, from the Polytechnic of Valencia. He does the GPS tracking not only to neonates, but also to reproductive females. This is how he has discovered incredible trips. Last year, for example, a turtle went to Mallorca, then to El Saler (Valencia) and then to Mojácar (Almería) to lay eggs. “The literature had never told us that a turtle would make nests 500 kilometers away,” he says.

And although scientists have managed to detect trips to Türkiye, what the turtles born here do not do is go out to the Atlanticeven though sometimes their parents do have this origin. “In Spain we are in the middle of the colonization process,” says Tomás.

#Valencian #accelerator #loggerhead #turtles #supplies #Mediterranean #males