A blood test successfully predicted theosteoarthritis of the knee at least eight years before telltale signs of the disease appeared on X-rays, Duke Health researchers report.

Anticipate the diagnosis of osteoarthritis

In a study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers validated the accuracy of the blood test that identifies key biomarkers of osteoarthritis. They showed that it predicted the development of the disease, as well as its progression, as demonstrated in their previous work.

The research touts the usefulness of a blood test that would be superior to current diagnostic tools that often do not identify disease until it has caused structural damage to the joint.

“Currently, you need to have an abnormal x-ray to show clear evidence of knee osteoarthritis, and by the time it shows up on the x-ray, the disease has been progressing for some time,” said senior author Virginia Byers Kraus. , M.D., Ph.D., professor in the departments of Medicine, Pathology, and Orthopedic Surgery at Duke University School of Medicine.

“What our blood test shows is that it is possible to detect this disease much earlier than our current diagnostics allow.”

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting approximately 35 million adults in the United States and causing significant economic and social impacts. While there is currently no cure, the success of potential new therapies may depend on identifying the disease early and slowing its progression before it becomes debilitating.

Kraus and colleagues have focused on developing molecular biomarkers that can be used both for clinical diagnostic purposes and as a research tool to aid in the development of effective drugs. In previous studies, blood biomarker testing has demonstrated 74% accuracy in predicting the progression of knee OA and 85% accuracy in diagnosing knee OA.

The current study further refined the test's predictive capabilities. Using a large UK database, the researchers analyzed the serum of 200 white women, half diagnosed with OA and the other half without the disease, matched by body mass index and age.

They found that a small number of biomarkers in the blood test successfully distinguished women with knee OA from those without, detecting molecular signs of OA eight years before many women were diagnosed with the disease via X-rays.

“This is important because it provides further evidence that there are abnormalities in the joint that can be detected by blood biomarkers well before X-rays can detect OA,” Kraus said. “Early-stage osteoarthritis could provide a 'window of opportunity' in which to halt the disease process and restore joint health.”

New blood test is more accurate in identifying progression of osteoarthritis

A new blood test that can identify the progression of knee osteoarthritis is more accurate than current methods, providing an important tool to advance research and speed the discovery of new therapies.

The test is based on a biomarker and fills an important gap in medical research for a common disease for which effective treatments are currently lacking. Without a good way to accurately identify and predict the risk of osteoarthritis progression, researchers have largely been unable to include the right patients in clinical trials to test whether a therapy is beneficial.

“Therapies are lacking, but it is difficult to develop and test new therapies because we have no good way to determine the right patients for therapy,” said Virginia Byers Kraus, M.D., Ph.D., professor of the departments. of Orthopedic Medicine, Pathology and Surgery at Duke University School of Medicine and senior author of a study that appeared online Jan. 25 in the journal Science Advances

“It's a tough, chicken-and-egg situation,” Kraus said. “In the immediate future, this new test will help identify people at high risk of progressive disease – those likely to have both pain and worsening damage identified by X-rays – who should be enrolled in clinical trials. Then we will be able to know if a therapy is beneficial.”

Kraus and colleagues isolated more than a dozen molecules in the blood associated with the progression of osteoarthritis, which is the most common joint disorder in the United States. It affects 10% of men and 13% of women over the age of 60 and is a major cause of disability.

With further refinement, the researchers narrowed the blood test to a set of 15 markers that correspond to 13 total proteins. These markers accurately predicted 73% of progressors versus non-progressors among 596 people with knee osteoarthritis.

The prediction rate for the new blood biomarker was far better than current approaches. The assessment of baseline structural osteoarthritis and pain severity has an accuracy of 59%, while the current biomarker analysis of urine molecules has an accuracy of 58%.

The new set of blood-based markers also managed to identify the group of patients whose joints show progression on X-ray scans, regardless of pain symptoms.

“In addition to being more accurate, this new biomarker has the added benefit of being a blood-based test,” Kraus said. “Blood is an easily accessible biological sample, making it an important way to identify people to enroll in clinical trials and those who are most in need of treatment.”

In addition to Kraus, the study's authors include Kaile Zhou, Yi-Ju Li, Erik J. Soderblom, Alexander Reed, Vaibhav Jain, Shuming Sun, and M. Arthur Moseley.

MRI definition developed for knee osteoarthritis (OA)

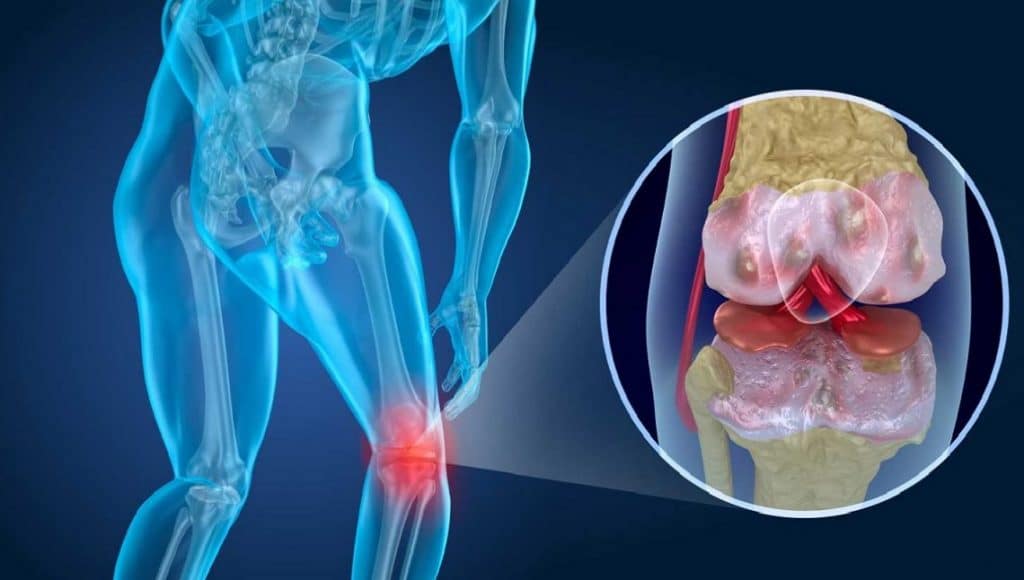

Knee osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative knee joint disease, is typically the result of progressive cartilage loss and low-grade inflammation. This common condition affects approximately 500 million adults worldwide and is a leading cause of pain and disability.

Despite this enormous public health burden, there are no effective approved treatments that can prevent osteoarthritis from worsening or progressing, and X-rays, the most common tool used to diagnose the condition, cannot easily detect it.

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is better at detecting these changes, there is no consensus definition of OA using MRI for use in research.

To address this problem, researchers at Boston University's Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine created and tested MRI definitions for OA using different combinations of knee OA features that can be seen on MRI.

“Developing a definition of knee OA using MRI will lead to better studies of potential treatments,” said first author Jean Liew, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine at the School.

Using data from a group of older adults, researchers created candidate (potential) MRI definitions using different combinations of knee OA features that can be seen on MRI. They then tested how these MRI definitions performed in detecting the disease.

An MRI definition of OA requiring cartilage damage and a small osteophyte (abnormal extra bone that forms in the knee joint) was the most accurate and simple marker for identifying OA.

According to the researchers, the main goal of OA research is to design studies of potential treatments in the hope that they will be able to identify effective treatments. “Due to its increased sensitivity in detecting joint tissue changes associated with OA, an MRI-based definition of structural disease would allow for accurate characterization of those who are eligible for studies testing treatments for OA and would enable the “inclusion of joints with earlier disease than based on X-ray alone,” added corresponding author David T. Felson, MD, MPH, professor of medicine.

The researchers point out that their study focuses on the use of MRI to define/detect OA in research only and does not examine the use of MRI to diagnose osteoarthritis in a clinical setting or intended to counsel patients or doctors in this way.

Can walking for exercise help prevent pain in people with knee osteoarthritis?

In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology that included individuals aged 50 and older with knee osteoarthritis, those who walked for exercise were less likely to develop frequent knee pain.

The study, which involved 1,212 participants, also found preliminary evidence that walking for exercise could change some of the structural effects of osteoarthritis on the knees.

“The Center for Disease Control recommends regular physical activity, such as walking for exercise, to reduce the risk of serious health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity and some cancers. Based on our findings, walking for exercise may also help people with knee osteoarthritis prevent regular knee pain and perhaps further damage to the joint,” said lead author Grace H. Lo, MD, MSc, researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, chief of rheumatology and research scientist at the Center for Innovations in Quality, Efficacy and Safety, at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas.

#Osteoarthritis #Blood #test #detects #years #appears #Xrays